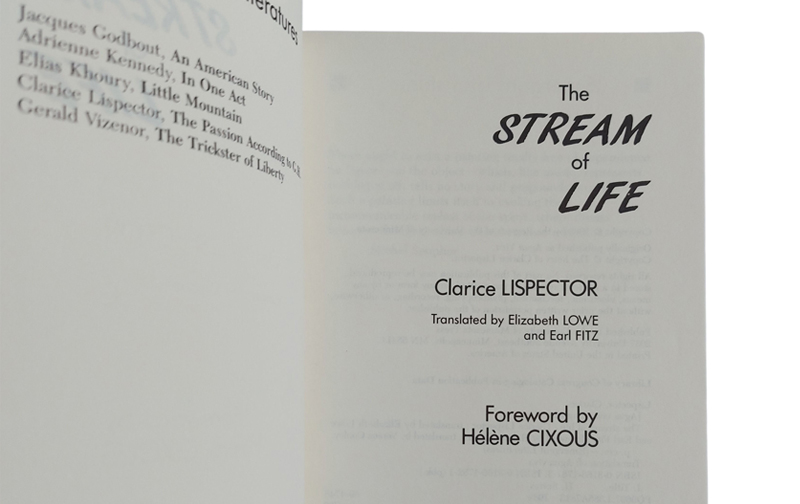

Clarice Lispector, one of the most influential and enigmatic writers of the 20th century, is known for her distinctive voice and innovative literary style. Her works, particularly The Stream of Life (A Hora da Estrela), stand out not only for their philosophical depth and psychological insight but also for their unique approach to language, narrative structure, and the themes of identity, consciousness, and existence. Lispector’s writing is often compared to high fashion, meticulously crafted, layered, and full of contradictions. It is a perfect example of how literary styles, like fashion, are cyclical, transformative, and highly dependent on the tastes and intellectual movements of their time. Lispector’s works, and particularly The Stream of Life, reflect the intersection of fashion and style in the literary world, a blending of narrative choices that challenge conventional storytelling while embracing deep explorations of human experience.

Lispector’s style can be described as experimental and introspective, characterized by a stream-of-consciousness technique, fragmented narrative, and vivid imagery. Her writing has often been compared to modernist and postmodernist authors like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, yet it retains a unique rhythm that reflects her own distinct voice. The text is fragmented, much like a work of high fashion, where every stitch, every layer, is carefully crafted, each detail significant, even though the overall effect may not always be immediately clear or easily understood. In The Stream of Life, this fragmentation is evident as Lispector’s characters often navigate through an array of disconnected thoughts, memories, and emotions that gradually piece together a coherent whole. This narrative style, while not always linear, becomes a fashion in its own right—one that celebrates individual perceptions and the fluid nature of experience.

Fashion, in the sense of its connection to art, plays a significant role in the way Lispector constructs her narratives. She doesn’t follow conventional rules of storytelling; instead, she subverts the traditional, opting for an approach that prioritizes psychological exploration over chronological structure. In The Stream of Life, the novel unfolds in a way that mirrors the internal chaos and emotional turbulence of its protagonist, Macabéa, a poor, uneducated young woman living in Rio de Janeiro. Lispector’s narrative choices are deliberate and calculated, designed to evoke emotions rather than simply tell a story. Like a fashion designer crafting a collection, Lispector arranges words, symbols, and motifs with a keen eye for texture, layering, and contrast. The result is a work that feels both intense and fragmented, but ultimately unified by the same deep undercurrent of existential questioning.

Lispector’s approach to writing is akin to the world of fashion, where clothing is not just a means of protection or modesty but a statement, an expression of identity and individuality. In The Stream of Life, fashion, or rather the lack thereof, becomes a metaphor for the social invisibility and existential poverty experienced by Macabéa. The young woman’s life is marked by a continual struggle against obscurity, as she is both literally and metaphorically ‘clothed’ in the poverty and marginalization that define her existence. Yet, despite her invisibility in the world around her, Lispector’s portrayal of Macabéa is anything but passive or simplistic. Through the lens of Lispector’s poetic and fragmented style, Macabéa is given a voice, a presence in the text that mirrors the complexities of the human condition, particularly the way in which identity is shaped by societal expectations and personal history. Fashion, in this sense, becomes an instrument through which the character’s struggle for self-identity is both obscured and revealed.

The fragmented nature of Lispector’s prose in The Stream of Life is akin to the art of haute couture, where every stitch, every detail matters. Yet, while her style is intricate and dense, it is never overly ornate or self-indulgent. Instead, it’s as though Lispector is weaving together a tapestry of human consciousness, capturing moments of beauty, pain, hope, and despair in short bursts of narrative. Just as a designer balances form and function, Lispector balances the beauty of her language with the weight of the themes she explores—loneliness, alienation, the search for meaning in a meaningless world. The texture of Lispector’s writing, its emphasis on both the tactile and the intangible, evokes a deep emotional response from the reader, pulling them into the mind of her characters and immersing them in the fabric of their experiences.

Lispector’s works are also heavily influenced by the intellectual and cultural movements of her time, particularly the rise of existentialism and modernism. Her writing reflects a deep engagement with these movements, particularly in its exploration of the human condition and the complexities of existence. Just as fashion evolves in response to societal changes and cultural shifts, Lispector’s writing mirrors the intellectual and political climate of Brazil during the mid-20th century. Her prose is a reflection of the tensions and contradictions of her time, and The Stream of Life is a direct engagement with issues of class, gender, and identity. The novel’s protagonist, Macabéa, is an outsider in society, and her experiences are marked by a constant tension between her desires for a better life and the harsh reality of her situation. In the same way that fashion can be a critique of social norms and power structures, Lispector’s novel critiques the way in which society marginalizes and dehumanizes individuals who do not conform to its expectations.

In The Stream of Life, Lispector’s critique of social expectations is embedded in the fabric of the novel itself. Just as fashion can be both a form of rebellion and conformity, Lispector’s writing pushes against the boundaries of conventional literature, offering a unique perspective on the human experience. Her characters do not conform to traditional archetypes; instead, they are fully realized individuals, flawed and complex, struggling to make sense of their lives in a world that seems indifferent to their existence. This literary fashion, like all great fashion, is both a product of its time and a reflection of the inner workings of the human soul. Lispector’s characters do not just exist; they question, they rebel, and they seek to understand the world around them in new and unexpected ways.

Critics have long struggled with how to categorize Lispector’s writing. Some view her as a modernist, others as a postmodernist, and still others as a feminist or existential writer. But Lispector’s work resists easy categorization, much like a groundbreaking fashion collection that blends influences from various periods, cultures, and traditions to create something entirely new. Her style is intellectual, dense, and often elusive, but also deeply emotional, poetic, and full of beauty. The Stream of Life has been praised for its daring narrative structure and its emotional depth, but it has also been criticized for its difficulty and its refusal to adhere to conventional expectations of what a novel should be. This division in critical reception is similar to how fashion is received: what is considered groundbreaking and avant-garde in one era can, in another, be deemed inaccessible or pretentious.

The reception of Lispector’s works has evolved over time, much like the changing tides of fashion. In the decades following the publication of The Stream of Life, Lispector’s work was celebrated for its boldness and complexity, but it also faced resistance from those who preferred more straightforward or traditional narratives. In recent years, however, Lispector’s reputation has undergone a resurgence, with scholars and critics rediscovering the depth and power of her writing. Just as fashion trends often return in cycles, Lispector’s style has once again become the subject of intense scholarly attention, with contemporary critics exploring her contributions to modern literature and her impact on the development of narrative forms. The current appreciation of Lispector’s work highlights how literary styles, much like fashion, are cyclical, with what was once considered unconventional or avant-garde becoming highly regarded in later years.

Lispector’s works, particularly The Stream of Life, continue to be celebrated for their aesthetic beauty, their intellectual rigor, and their emotional depth. Her writing, like the best of high fashion, transcends time and place, offering readers a glimpse into the complexities of the human soul. Her use of language, narrative structure, and symbolism creates a world that is both strange and familiar, one that invites the reader to reflect on their own existence and the meaning of life. In many ways, Lispector’s writing serves as a reminder that literature, like fashion, is not simply about following trends or conforming to expectations. Instead, it is about creating something new, something that challenges the status quo, and something that speaks to the deepest parts of the human experience. Through her literary fashion, Lispector has crafted a body of work that continues to resonate with readers around the world, offering a timeless exploration of identity, consciousness, and the pursuit of meaning.