In an age when fashion is more global and interconnected than ever, designers face a paradox: they have built a strong brand identity and signature style, yet they must continually engage with new, international influences. Coco Chanel’s maxim — “Fashion changes, but style endures” — captures the ideal that a designer’s own aesthetic should remain distinct even as clothes and trends evolve. Historically, couturiers like Chanel, Yves Saint Laurent or Christian Dior established legacies of timeless style precisely by defining an original vision and then weaving in broader cultural threads on their own terms. As Chanel herself warned, “to be irreplaceable one must always be different” . In other words, authenticity and difference were at the core of “who we are” as Anna Wintour has emphasized .

Yet in today’s cosmopolitan fashion system – one driven by social media, global retail and digital culture – designers must remain open to fresh input. The industry’s globalization has undeniably introduced new voices, fabrics, and stories into what once might have been a narrowly Paris-centric or Milan-centric conversation. Some veterans mourn this shift. Costume designer Patricia Field, for example, has observed that “as a result of globalization [the industry] has undergone uniformity” , suggesting that too much sameness is emerging on runways worldwide. Even if one agrees with that caution, the challenge for a designer now is to harness global diversity without succumbing to uniformity or trend-chasing. In practice, the most creative labels today embrace cross-cultural inspiration in a way that deepens their own identity. As one analysis of young designers put it, the lines between art, fashion and other media are blurring: those who “decline to stay in their lane” and mix disciplines often find it a savvy way to build their brand . In short, cosmopolitanism in fashion means looking outward and incorporating global dialogues, but doing so through the filter of a personal vision.

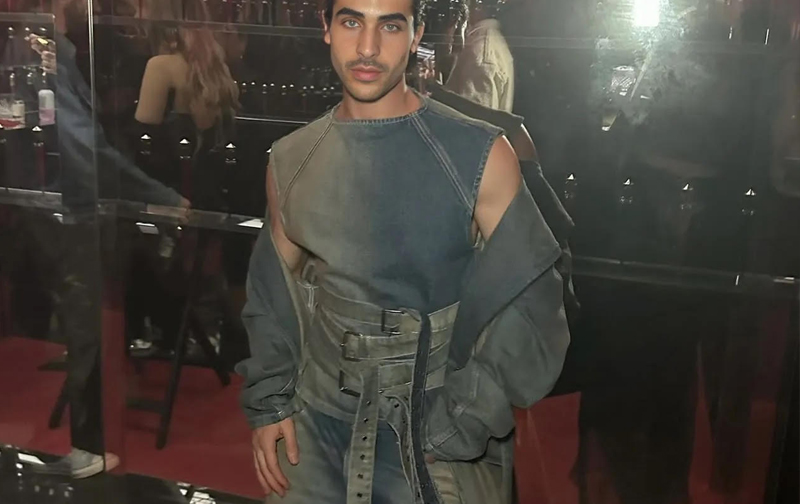

A useful touchstone is Anna Wintour’s advocacy of original style over slavish trend-following. She famously said she is “not interested in the girl who walks into my office in a head-to-toe label look that’s straight off the runway. I’m interested in a girl who puts herself together in an original, independent way” . This remark underscores a central prescription: mix and experiment, but always with an original hand. Similarly, Gianni Versace urged fashion-lovers not to become “fashion victims” by blindly chasing trends: “Don’t be into trends. Don’t make fashion own you, but you decide what you are, what you want to express by the way you dress” . Versace’s call to personal authority echoes Wintour’s counsel to remain “true to yourself” . In effect, these icons argue that openness to new styles should be governed by one’s own style compass. A designer with a signature aesthetic can thus wear pieces from other labels or collaborate freely, as long as the outcome feels authentic. Even when knee-deep in today’s trends and global influences, they should avoid feeling like a passive “font of label clichés,” as Wintour might put it. Instead, each borrowed element should be a deliberate choice that furthers the label’s voice.

This balance between global influences and individual authenticity has deep roots. Historically, major designers from the mid-20th century onward drew on diverse sources while keeping a core style. Chanel herself liberated women by simplifying silhouettes (introducing menswear fabrics and jersey) yet always maintained the clean, understated lines of her house . Similarly, Yves Saint Laurent famously proclaimed that “fashions fade, style is eternal” (YSL’s own phrasing of Chanel’s idea) . He absorbed everything from Russian folk embroidery to Mondrian’s art in his collections, but his collections always felt unmistakably “Yves Saint Laurent.” The lesson is consistent: ideas flow in from everywhere – art, street culture, history, technology – but the designer filters them. Diane von Furstenberg has captured this elegantly: “Style is something each of us already has, all we need to do is find it” . In other words, a brand’s enduring style emerges from its founder’s personal vision; outside influences should be tools to refine and express that vision, not erase it.

Contemporary fashion’s cosmopolitan ethos extends far beyond clothing design. It encompasses how designers converse with the world. Vogue Business has noted that young creatives today are “declining to stay in their lane” – for instance by staging exhibitions or cross-disciplinary projects – to set their brand apart . Grace Wales Bonner, for example, mixes music and art installations into her shows, while Thebe Magugu’s runway was accompanied by a photo exhibit exploring South African heritage. These moves illustrate a broader point: a designer’s brand can be enriched by dialogue with other fields. A designer need not become an “artist” in the fine art sense, but collaborating with filmmakers, musicians or even furniture designers can deepen a collection’s meaning. The case of Virgil Abloh exemplifies this vividly. Abloh, founder of Off-White and then menswear director at Louis Vuitton, consciously straddled the boundaries between streetwear and luxury. As British Vogue reported, Off-White “bridges the gap between streetwear and luxury fashion” and has become a global phenomenon from sweatshirts to tulle ballgowns . Abloh attributed part of this success to his network of mentors: he told Vogue that his role at Louis Vuitton was “directly attributable to work Nigo’s done in the past,” and that their LV×NIGO collaboration was about giving credit and context to each other . In that project, he insisted, “Let’s not do the expected. Let’s not put streetwear in a box” . In practical terms, Abloh took iconic elements of street culture (hoodies, sneakers) and reimagined them in the ornate house of Vuitton – often side by side with traditional suiting – showing that collaboration with other aesthetic legacies can be bold yet harmonious. His point, elaborated in Vogue, was that true “fashion with a capital F… is supposed to take you on a journey, to lead” . In other words, mixing styles and partnering with other brands can produce something new that advances fashion rather than simply echoing the status quo.

Other modern designers echo this collaborative, outward-facing approach. For instance, Alessandro Michele at Gucci expanded his label’s 1970s-inspired maximalism by collaborating with cultural icons from Sesame Street to Disney, always stamped with Gucci’s eclectic eyewear and layering. Jonathan Anderson at Loewe marries his Irish background with Spanish artisanal influences and even Japanese craft in his collections. Even mainstream giants engage this way: Prada and Adidas launched their “Prada Marfa” sneaker collabs, balancing sportwear with Prada’s sleek aesthetic. Such examples show that even legacy brands can adapt by working with others. In each case, the collaborations are chosen so that the final pieces still “speak” the brand’s language, however enriched by a guest note.

Crucially, wearing or sourcing other labels need not dilute a designer’s brand identity if done thoughtfully. If a designer publicly champions sustainability, for example, they might joyfully wear a vintage piece from another house or upcycle discarded fabrics, in line with their values. Edward Enninful, editor-in-chief of British Vogue, once recalled how as a young man with little money he would buy a second-hand jacket and personalize it, simply because he loved the idea it represented . This exemplifies how clothing – any clothing – can be a canvas for individual expression. Marc Jacobs similarly emphasized that fashion “is for everyone: owning a dress isn’t what it’s about… if you can experience fashion, if it moves you or inspires you… that’s what creativity does: it stimulates and inspires people. Ownership isn’t the important thing” . They point to a creative attitude: a good designer can remix pieces, hack them, combine luxury and thrift. A well-curated wardrobe is not limited to one brand or price tier. Thus a designer with a “own vibe” might pair their runway coat with a street-style accessory, or take inspiration from emerging designers halfway across the world. This kind of open-mindedness – wearing others’ work or collaborating across labels – is now expected of fashion leaders.

Nevertheless, there remains a caution against becoming overly diffuse or trend-driven. Fashion commentators often use the term “fashion victim” to describe those who let ephemeral trends entirely dictate their look. The advice from Versace and Wintour speaks to this: be selective. Don’t abandon your brand’s DNA in the name of relevance. Balancing this is nuanced. One practical rule is to adopt what feels genuinely exciting. For example, Demna Gvasalia – who has helmed Vetements and Balenciaga – warned against the “sell-out trap” that can ensnare successful labels, implying that success makes it tempting to chase every new trend . (Gvasalia himself mixes pop references with classical tailoring at Balenciaga, yet each piece still looks undeniably like his creation.) Tactically, a designer might choose one cross-brand element per collection – say, a Nike track stripe on a Dior coat – rather than slavishly layering every hot logo. Collaborations (from H&M’s designer pairings to Off-White’s Nike lines) should be framed as creative dialogues, not just marketing stunts. The high-profile collabs of recent years show that many brands believe there is value in sharing aesthetics, but the underlying brands usually maintain control over the narrative.

To stay current without losing authenticity, thoughtfulness is key. As Anna Wintour put it, a designer cannot “look too much to the left and the right about what the competition is doing. It has to be a true vision” . In other words, one can be inspired by others, even collaborate with them, but the final concept must have unity. Practically, this might mean incorporating, say, African prints, tech fabrics or street-style cuts into a collection only if they can be given the house’s characteristic finish. When Louis Vuitton worked with Supreme, Kim Jones ensured the logo mash-up also felt luxurious. When Fendi and Versace (two storied houses) teamed up, it was to create a mutual fusion rather than subsume one under the other.

In the contemporary global fashion world, style thinking is inherently cosmopolitan: designers often draw on music, architecture, travel and social issues as much as fabric suppliers. Miuccia Prada encapsulated this by noting that “what you wear is how you present yourself to the world, especially today, when human contacts are so quick. Fashion is instant language” . This means that a garment speaks not only through its cut but through its references. A label might signal cosmopolitanism by using a fabric from Thailand in Paris or by featuring New York graffiti on Milan runways. But the label’s unique vocabulary should remain the voice behind these messages. A David Bowie of design, in a way, who can zigzag genres but still recognizes their own bassline. Alexander McQueen understood a kindred idea when he said, “I think there is beauty in everything… I can usually see something of beauty in it” . This ceaseless curiosity – to see potential everywhere – is what allows fashion to stay fresh.

Ultimately, fashion today rewards those who can confidently combine the global and the personal. A designer with a signature style should indeed embrace a cosmopolitan outlook and celebrate collaboration: mixing casual and couture on the runway, taking inspiration from other houses, or partnering with artists and brands far beyond the traditional fashion orbit. This openness cultivates creativity, as Jacobs and Enninful reminded us, by encouraging the “idea of what you can be” beyond mere purchasing . But they also stressed ownership of that creative spark. By heeding Wintour’s charge to “create your own individual style” and Versace’s warning not to let trends “own you” , designers can navigate the new fashion ecosystem. They remain the author of their brand’s story even while inviting new chapters from the world around them. In this way, they stay relevant in today’s globalized fashion arena without ever becoming fashion victims. In the end, as Diane von Furstenberg said, each person has a style already within them – a designer’s job is to continually refine and express that style, enriched (but not overshadowed) by the cosmopolitan currents of their time .