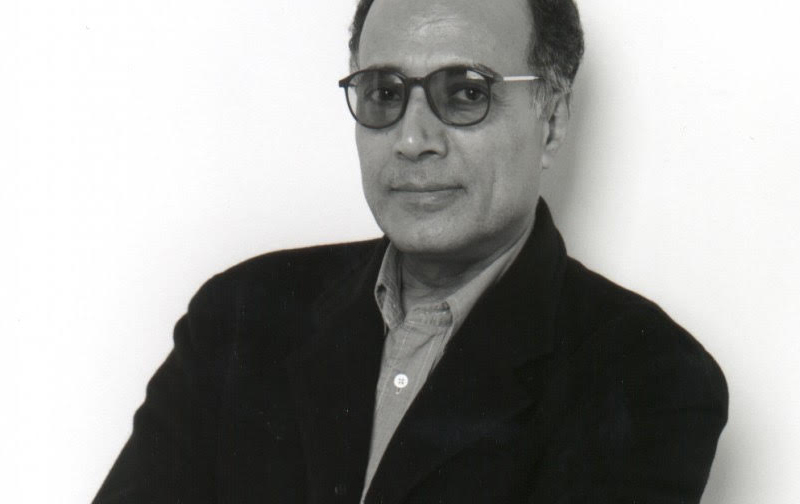

Abbas Kiarostami (1940–2016) is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential filmmakers in Iranian and world cinema . His body of work blended fiction and documentary, minimalism and spontaneity, poetic vision and humanist spirit , forging a unique cinematic language that transcended cultural boundaries. Jean-Luc Godard famously remarked that “cinema begins with D.W. Griffith and ends with Kiarostami” , reflecting the immense esteem Kiarostami earned among cineastes worldwide. Kiarostami’s films are philosophical and deeply immersive, often blurring the line between reality and fiction in order to explore universal themes of life, death, and human dignity . Over a four-decade career, he singlehandedly put Iran on the map of world cinema with works that won international acclaim and profoundly influenced filmmakers across the globe .

He was born in Tehran in 1940 and initially pursued painting and graphic design at university, even working briefly as a traffic police officer – a job that attuned him to observing everyday social interactions and the choreography of people in motion . In the 1960s, Kiarostami worked as a graphic artist, designing film credits and directing commercials, before joining the Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (Kanun) in 1969 to establish its filmmaking department . There he made his directorial debut with the lyrical short Bread and Alley (1970), a vignette about a young boy confronting a stray dog. This simple 12-minute film – produced in neorealist fashion with non-actors on real locations – already showcased the improvised performances, documentary textures, and real-life rhythms that would define his style . Kiarostami’s early films often centered on children and everyday situations. His first feature, The Traveler (Mossafir, 1974), follows a resourceful boy who journeys from his rural town to Tehran to attend a football match – an “indelible portrait of a troubled adolescent” that combines poignant social observation with a child’s-eye view of adventure. Through the late 1970s he continued to make both short and feature-length works – including dramas like A Wedding Suit (1976) and The Report (1977) – steadily honing a minimalist, observational approach to filmmaking.

In the 1980s, despite the upheavals of the Iranian Revolution, Kiarostami remained in Iran and continued working at Kanun, producing films under the new cultural limitations. He made several short documentaries and educational films focusing on children, such as First Graders (1984) and Homework (1989), which offered insightful commentary on the experiences of Iranian youth. His breakthrough on the international stage came with Where Is the Friend’s Home? (1987), a gentle yet deeply affecting tale of a schoolboy’s quest to return his friend’s notebook to a neighboring village. Told from a child’s perspective and set against the rural northern Iranian landscape, this film was noted for its poetic simplicity and realism . Where Is the Friend’s Home? earned Kiarostami his first major acclaim outside Iran – winning awards at international festivals and bringing him to the attention of cinephiles worldwide . The film’s humble story and humanist message resonated broadly, effectively launching Kiarostami as a new voice in world cinema. (It would also become the first part of what later came to be known as Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy.)

In 1992, Kiarostami returned to the setting of Where Is the Friend’s Home? after a devastating earthquake struck northern Iran, and crafted the acclaimed film Life, and Nothing More… (also titled And Life Goes On). In this semi-fictional docudrama, a filmmaker (portrayed by an actor) drives with his young son to the quake-ravaged region in search of the child actor from Friend’s Home, encountering survivors and scenes of devastation . For the first time, the theme of mortality subtly and maturely crept into Kiarostami’s cinema, as the director-character’s journey becomes a meditation on loss and perseverance amid ruins . Kiarostami followed up with Through the Olive Trees (1994), a metacinematic story that unfolds during the filming of And Life Goes On…. Focusing on a romantic subplot – a local stonemason’s persistent courtship of a young actress amid a film production – Through the Olive Trees provided a fittingly self-reflexive coda to the trilogy . These three films, collectively known as the Koker Trilogy (after the village where they take place), ingeniously blur the boundaries between fiction and reality. Kiarostami plays with nested narratives and open endings – for example, the final scenes of Life and Nothing More and Through the Olive Trees withhold key dialogue from the audience, forcing viewers to imagine the off-screen conversations for themselves . This inventive approach earned the trilogy worldwide admiration for its elegant simplicity and profound depth: Kiarostami uses the aftermath of real-life disaster as the canvas for exploring universal themes of life, death, and the healing continuity of ordinary existence.

Between the first two installments of the Koker Trilogy, Kiarostami directed Close-Up (1990), which has since become one of his most celebrated works. Close-Up is a genre-defying docufiction masterpiece that reenacts a bizarre true incident in Tehran: an impoverished movie buff named Hossein Sabzian, pretending to be the well-known director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, ingratiated himself into the life of a middle-class family and was later arrested for fraud. Fascinated by the case, Kiarostami obtained permission to film Sabzian’s actual trial and also convinced the real people involved – Sabzian, the family he deceived, and even Makhmalbaf himself – to portray themselves in a reconstruction of the events . The resulting film brilliantly collapses the distinction between reality and performance. As one critic noted, Close-Up is a demonstration of “the futility of any attempt to draw a clear line between documentary and fiction” – a lie becomes truth, and the act of filmmaking itself becomes part of the story. Though modest in scale, Close-Up has had an outsized influence, frequently appearing on lists of the greatest films ever made (in the 2022 Sight & Sound poll of directors, it was ranked among the top 20 films of all time ). The film is a poignant human drama – sympathetic to Sabzian’s dreams and social struggles – as well as a witty inquiry into the nature of cinema. It epitomizes Kiarostami’s genius for finding poetry in real life and for turning the camera back onto the process of storytelling itself.

Kiarostami reached the peak of his international fame in the late 1990s with two widely celebrated features. Taste of Cherry (1997) follows a middle-aged man, Mr. Badii, who drives through the outskirts of Tehran searching for someone willing to perform a difficult favor: to bury him quietly if he succeeds in killing himself at the end of the day . Despite its morbid premise, the film is contemplative rather than bleak – much of it consists of philosophical conversations between Badii and the strangers he picks up (a Kurdish soldier, an Afghan seminarist, a Turkish taxidermist), each reacting differently to his request. Taste of Cherry was awarded the Palme d’Or at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival (in a tie, shared with Shohei Imamura’s The Eel) , marking a historic first win for Iranian cinema at Cannes. The film’s minimalist style – long takes of the protagonist’s vehicle crawling across dusty hills, dialogue that often gives way to meditative silence – and its daring unconventional ending (in which the narrative’s resolution is deliberately left ambiguous, followed by a fourth-wall-breaking video epilogue of the film crew) have made Taste of Cherry a touchstone of modern art-house cinema.

In The Wind Will Carry Us (1999), Kiarostami returned to rural Iran with a story about a Tehran engineer and his crew who travel to a remote Kurdish village ostensibly to document a traditional funeral ceremony. As they wait for an elderly woman’s expected passing, the film becomes an ironically gentle study of the rhythms of village life and the presence of death. The Wind Will Carry Us is told in a highly elliptical manner – many important characters (the sick old woman, a long-distance phone operator, a man digging a ditch) are never seen directly on screen , and much of the action is subtle or implied. This deliberate withholding creates a sense that the most vital elements are invisible, just beyond our frame of view. Kiarostami himself described the film as an exploration of “being without being,” wherein absence itself becomes a form of presence . The title comes from a poem by Forough Farrokhzad about the transience of life, underlining the film’s reflective, poetic dimension. Together, Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us confirmed Kiarostami’s status as a revered auteur on the world stage, celebrated for his spare, patient storytelling and profound philosophical undertones.

Entering the 2000s, Kiarostami embraced digital video and experimental forms. He directed the documentary ABC Africa (2001) in Uganda, using a lightweight DV camera to record the lives of children orphaned by civil war and AIDS . In Ten (2002), he mounted two small digital cameras on the dashboard of a car and crafted a film out of 10 conversations between a young Iranian female driver and her passengers as she navigates the streets of Tehran . The characters – including the driver’s angry little boy, an old peasant woman, a heartbroken bride, and a devout sex worker – collectively present a cross-section of contemporary Iranian society, especially the experiences of women. Ten’s innovative technique and intimate, conversation-driven format won praise as a bold new kind of realism for the digital age.

Kiarostami continued to push formal boundaries with Five (2003, subtitled Five Dedicated to Ozu), an experimental tribute to Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu consisting of five extended single-shot scenes of nature, shot along the shores of the Caspian Sea . In this film there are no human characters at all – only waves breaking on a beach, ducks wandering by a pond, dogs barking at night – inviting the viewer into a meditative state and testing the limits of narrative cinema. Similarly, in Shirin (2008), Kiarostami subverted expectations by never showing what most viewers would consider the “main” action: the film depicts an audience of 110 Iranian women watching a movie (an adaptation of a Persian love story) that is heard on the soundtrack but never shown on screen . Instead, the camera stays on the faces of the women in the dark theater, capturing the emotions evoked by the unseen drama. This concept turned the act of watching a film into the subject of the film itself – a meta-commentary on cinema and audience empathy. In these works, Kiarostami deliberately eschewed conventional narrative and even characterization , pursuing what he called a “pure cinema” of observation and experience. During this period, he also extended his artistry to other media – publishing collections of his poetry and showcasing his photography – underscoring the unity of his poetic vision across different forms .

In the last decade of his career, Kiarostami ventured abroad for new inspirations and collaborations. Certified Copy (2010) marked several firsts: it was Kiarostami’s first feature made in Europe, his first to use a professional Western actress in a lead role, and essentially his first overt foray into a more dialogue-heavy, relationship-driven drama (though still very much filtered through his unique lens). Filmed in Tuscany and starring Juliette Binoche and opera singer William Shimell, Certified Copy follows a British author and a French gallery owner who meet at a lecture and spend a day together in a scenic village – during which they begin to ambiguously role-play as a long-married couple, or perhaps reveal that they truly are one. The film avoids certainties about the pair’s relationship, instead offering a “copy” of a romance that might itself be an original love unspoken . This playful treatment of authenticity versus imitation, set against European art and architecture, echoed some of Kiarostami’s long-standing themes (the blurred line between reality and performance) in a new cultural context. Binoche’s performance earned her the Best Actress award at Cannes, underlining how effectively Kiarostami’s directorial approach could draw out nuanced emotions even in a language (English and Italian) not his own.

Kiarostami’s next and ultimately final narrative feature was Like Someone in Love (2012), produced in Japan with a Japanese cast. It tells the story of a young student in Tokyo who works nights as an escort, her jealous fiancé who remains unaware of her secret, and an elderly professor who forms a fleeting connection with her . Over the course of two days, these characters’ lives intersect in ways that touch on themes of loneliness, identity, and mistaken assumptions. Though set in an urban Japanese milieu, Like Someone in Love is crafted with the same observant, unhurried eye that Kiarostami brought to the villages of Iran – including extended car rides through Tokyo where conversations play out in real time. The film builds to an abrupt, enigmatic ending that leaves a confrontation unresolved, again challenging viewers to ponder what might happen beyond the closing frame.

For several years afterward, Kiarostami worked on what would become his final film: 24 Frames. Completed after his passing (he died in July 2016 in Paris, following complications from surgery), 24 Frames (premiered 2017) is an experimental project consisting of two dozen short vignettes, each inspired by a single still image – either one of Kiarostami’s own photographs or a famous painting – which is then digitally animated to imagine what might have happened before or after that frozen moment . In each “frame,” the camera remains mostly fixed as subtle movements or events unfold: we see, for example, Pieter Bruegel’s landscape Hunters in the Snow come to life with falling snow and wandering animals, or we watch a static seaside photograph gradually animated by waves and gulls. Entirely dialogue-free and almost plotless, 24 Frames invites the viewer into a final meditation on time, image, and memory – a graceful epilogue to Kiarostami’s career, in which he returns to the fundamental elements of cinema (light, movement, nature) and, one last time, asks us to observe patiently and dream within the frame.

Throughout his oeuvre, Kiarostami maintained a distinctive artistic philosophy that sets his films apart. He is often celebrated as a poet of cinema, not only because he wrote poetry (which he did, prolifically), but because his films embody a poetic sensibility in their use of imagery, rhythm, and allusion. In fact, Kiarostami frequently drew direct inspiration from Persian poetry: classic poems are quoted or recited within films like Where Is the Friend’s Home? and The Wind Will Carry Us, establishing an intimate link between his cinema and Iran’s literary heritage . The very title The Wind Will Carry Us is taken from a poem by Forough Farrokhzad, and the film’s dialogue and themes subtly reflect that poem’s meditation on fleeting life. This integration of poetry contributes to the lyrical quality of Kiarostami’s storytelling – a quality manifested in his preference for visual metaphors (a winding mountain road, a tree silhouetted against the sky) and his embrace of simplicity and silence.

Narrative ambiguity is another hallmark of Kiarostami’s style. His films characteristically contain an “unusual mixture of simplicity and complexity” and often leave significant interpretive gaps . Kiarostami believed in engaging the audience as active participants rather than passive consumers of a predetermined message. To that end, he frequently omits conventional plot resolutions and even key pieces of information, thereby forcing viewers to fill in the blanks with their own imagination . As critic Jonathan Rosenbaum observed, what Hollywood would consider essential narrative details are often missing in Kiarostami’s films, and yet those very absences become the source of the films’ profundity . Kiarostami articulated his approach in one interview, saying: “I want to create the type of cinema that shows by not showing… to give the audience the chance to create as much as possible in our minds, through imagination” . In other words, by deliberately not showing certain events or by obscuring certain perspectives, he opens a space for the viewer’s creativity to complete the picture. This philosophy is evident in moments such as the minute-long blackout at the end of Taste of Cherry or the unseen crucial characters in The Wind Will Carry Us – devices that draw attention to what lies outside the frame, suggesting that reality is far richer than what we directly see.

Kiarostami’s commitment to realism was deeply humanistic. He eschewed professional actors in many of his works, preferring non-actors who brought an unvarnished sincerity to their roles. “Quoting screenwriter Cesare Zavattini,” one commentator notes, “Kiarostami claimed that the first ordinary person on the street walking into his frame could be his protagonist.” Indeed, he proved that there is nothing “ordinary” about ordinary people , building stories around schoolboys, housewives, taxi drivers, and old villagers – individuals rarely seen in mainstream cinema. When working with these non-professionals, Kiarostami would often film them in long takes and engage them in real conversation rather than dictate strict lines, resulting in performances that feel spontaneous and true to life. His actors appear, as one critic put it, “realistically unreal” – they behave like people going about their lives (pausing, stumbling, reacting in unpredictable ways) even as they serve the film’s narrative needs . This method gives his films a quasi-documentary texture. At the same time, Kiarostami was a formalist who carefully composed each shot (he famously often wore dark sunglasses while directing, like a painter contemplating a canvas). He often used lengthy static shots that allow the audience to wander with their eyes within the frame, and he paid great attention to natural sounds – wind in the trees, footsteps on gravel, a distant bird – which create an immersive ambient atmosphere.

A signature setting in Kiarostami’s films is the interior of a car. From the earliest works to his last, he repeatedly used car journeys as a narrative device and a thematic space. Conversations in cars form the backbone of Taste of Cherry, Life and Nothing More, Ten, Certified Copy, Like Someone in Love, and more. Within the car’s confined environment, characters of different backgrounds are brought face-to-face, making the vehicle a microcosm of society. In Ten, for example, the driver’s various passengers – her angry child, a jilted bride, a sex worker – represent a tapestry of Iranian social life within the single space of a car, illustrating how “various cultures form one national identity, while acknowledging underlying tensions” . Moreover, the car window provides a moving frame through which we observe the outside world. Kiarostami often positions the camera to capture the passing landscape or people on the roadside, thus emphasizing the act of looking. This technique extends his motif of inviting the audience’s imagination – we glimpse fragments of lives through the car window and are prompted to consider the vast world beyond the immediate story .

Spiritually, while Kiarostami’s films are not overtly religious, they evoke a sense of contemplation that has been compared to Sufism and other mystical traditions . His narratives embrace uncertainty and serendipity, suggesting that truth is often found in moments of doubt or ambiguity. French philosopher Alain Badiou observed of Kiarostami’s cinema that “the absent is part of the image’s presence” – an idea that resonates with the Sufi concept of the unseen divine or the idea that what is missing can be as significant as what is there. In Kiarostami’s films, an unseen character, a silence, or an open ending can carry profound weight. Ultimately, he maintained that film should pose questions rather than impose answers. He once said that if his films have any message, it is to encourage “a kinder, more understanding view of humanity.” That empathetic, inquisitive perspective is what gives his otherwise quiet films a powerful moral undercurrent.

Abbas Kiarostami’s legacy in cinema is monumental. By the end of the 20th century, he had gained a reputation as arguably the most important Iranian filmmaker of all time . He received at least seventy awards by the year 2000 alone , and major festivals around the world continued to honor him throughout his career. In 2005, the British Film Institute awarded him a BFI Fellowship for his contributions to film culture . In a 2006 critics’ poll, The Guardian named Kiarostami the best contemporary film director in the world outside of the U.S. . Tributes from fellow directors testify to his towering status: the Austrian auteur Michael Haneke ranked Kiarostami among the very best of living directors ; Martin Scorsese praised him as an artist who “represents the highest level of artistry in the cinema” ; and Jean-Luc Godard’s famous pronouncement – that “cinema starts with D.W. Griffith and ends with Abbas Kiarostami” – has become legend . Perhaps most touchingly, Akira Kurosawa, one of cinema’s great masters, said that when the Bengali filmmaker Satyajit Ray died, he felt despair, but after seeing Kiarostami’s films, “I thanked God for giving us just the right person to take his place” .

Within Iran, Kiarostami inspired a generation of new filmmakers and put Iranian cinema on the international map. Directors such as Jafar Panahi, Asghar Farhadi, and Samira Makhmalbaf have all acknowledged his influence. Kiarostami often collaborated with or mentored younger directors – famously, he co-wrote the story for Panahi’s debut The White Balloon (1995), which won the Cannes Camera d’Or . Despite his global acclaim, he remained a humble figure at home, continuing to live and work in Tehran and often screening his films to small local audiences. For many years, Iranian authorities refused to screen some of his later films domestically, wary of their content or simply perplexed by his avant-garde style, but Kiarostami responded calmly, saying the officials just “don’t understand my films” and want to prevent any unintended message from getting out . He chose to avoid overt political confrontation, and in doing so he managed to keep creating within the system, bringing Iranian art to the world on his own terms.

Kiarostami passed away on July 4, 2016, in Paris, after complications from gastrointestinal surgery. His death prompted an outpouring of grief and appreciation across the film world. Thousands attended his funeral in Tehran, where figures like Asghar Farhadi spoke about Kiarostami’s immense contributions , and countless tributes were published by critics and filmmakers globally, all testifying to the profound impact of his work. While Kiarostami is no longer with us, his films continue to live and grow. They do so in the minds of viewers – each new audience bringing their own meanings to his open-ended creations – just as he intended. In the final moments of Taste of Cherry, we watch Mr. Badii lie down in his grave on a moonless night as a thunderstorm brews, and then the film abruptly cuts to a daytime video of Kiarostami’s crew wrapping up the shoot, with Louis Armstrong’s “St. James Infirmary” playing in the background . It is a jarring and unconventional ending, one that reminds us that what we have seen is a film, a constructed piece of art. Kiarostami often ended his films with such enigmatic flourishes – a deliberate invitation to reflect on reality versus illusion. Now, looking back at his remarkable career, we can appreciate that he took cinema itself on an “exhilarating detour” , showing new ways to tell stories and to engage our hearts and minds. Abbas Kiarostami’s vision, much like the final image of a lone car winding its way down a country road, continues to lead us toward unexplored horizons in cinema.