Personal style in Iran has long been “a proxy battle” for ideological conflict – a point underscored by scholars who note that dress can “communicate the wearer’s participation in a lineage of Leftist political aesthetic” . In other words, what Iranians wear has often signaled their political identity. Before 1979 the Shah’s regime encouraged Western fashions (even banning the veil as a supposed sign of backwardness ), but the revolution inverted this: modest, utilitarian clothing became a badge of revolutionary zeal. Ali Shariati himself framed this in starkly anti-imperialist terms, arguing that “Asian societies… wear traditional garments” and had “no demand… for high fashion… of Europe” . For many on the left, rejecting Western-style dress was part of reclaiming an Iranian identity – a practical example of Al-e Ahmad’s warning that adopting “Western models… led to the loss of Iranian cultural identity” . In short, by 1979 clothing was a distinctly political language, one that Iranian leftists are reviving today as part of a global pattern of anti-hegemonic fashion .

The politicization of dress was perhaps most visible in women’s protests. On International Women’s Day 1979, over 100,000 women marched in Tehran unveiled and defiantly smiling【131†】 . This mass demonstration against the new compulsory hijab shows how attire itself became a symbol of resistance. Before the revolution, unveiled dress was normalized; in fact the Shah had banned the hijab as “suppressing women” . When the new regime demanded the headscarf, abandoning or removing it became an act of political defiance. As one analyst notes, “donning the hijab became a tool of revolutionary advocacy… representing opposition to the Shah” . Revolutionary women’s clothing thus inverted the state narrative: wearing a traditional Islamic shawl was encouraged by the Islamists as anti-imperialist, whereas prior Westernized attire was “portrayed as morally corrupt” . In short, the veil and its absence were weaponized as ideological symbols during that era.

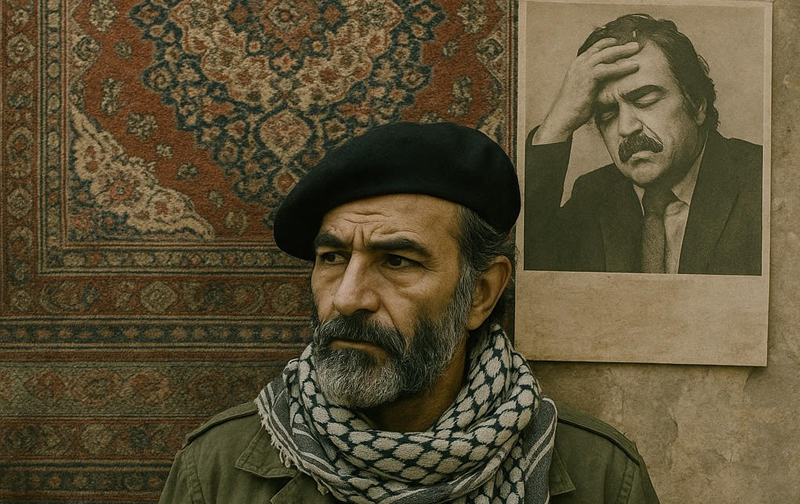

Men’s fashion underwent a parallel transformation. Street scenes from 1979 often show young men in olive-green or khaki “people’s army” jackets brandishing rifles. One famous image (above) captures a band of revolutionaries in exactly this garb: simple combat jackets and raised fists. Observers like V.S. Naipaul described these militants wearing “quilted khaki jackets and pullovers” as if in a “Che Guevara costume,” still eager to manifest the union they believed had won them victory. The Atlantic likewise noted how the new Revolutionary Guard imitated Che’s style, with its “Che Guevara outfits” and posters of Third World guerrillas . This militant attire — in contrast to the previous regime’s suits and ties — broadcast a leftist/Islamist creed: an embrace of egalitarian, anti-imperialist solidarity. In fact Islamic leaders themselves encouraged such modes. After the Shah fell, Islamists urged men to grow beards, discard Western suits, and wear “heavy linen robe[s] in muted colors” as a mark of authentic resistance . By wearing khaki jackets and military-style clothing, Iranian revolutionaries of various stripes (both secular left and Islamist) signaled membership in a global revolutionary style that prized uniformity and modesty over Western consumerism .

This fusion of politics and fashion was deeply theorized by Iran’s own intellectuals. In the 1960s and ’70s, Ali Shariati argued that traditional dress was part of a larger anti-colonial strategy: the very act of not importing “high fashion” was a rejection of foreign domination . Similarly, Jalal Al-e Ahmad’s pamphlet Occidentosis identified Western clothing as one of the “toxins” of imperialist culture. He warned that the imitation of Western models in education and art “led to the loss of Iranian cultural identity” . In the revolutionary moment, these ideas were lived out in fabric: khaki jackets and keffiyehs expressed Shariati’s call to “return not to a distant past, but a past present in daily life” , while rejection of Western-style dress enacted Al-e Ahmad’s critique of gharbsadegi. In this view, Iranian fashion of 1979 became overtly ideological: each jacket, scarf, or veil was a statement of anti-imperial identity.

Writers like Gholamhosein Saedi captured the attitude and its discontents in metaphor. Saedi later lamented that after the revolution a “wonderfully beautiful carpet” of ideals had been lifted only to reveal “worms and filth” beneath. His stark image (a preserved Persian carpet hiding decay) suggests that the very clothing and rituals of the revolution – no matter how poignant – were masking deeper turmoil. For Iranian leftist thinkers, even revolutionary style could become a double-edged sword: at once a symbol of hope and a reminder of contradictions. Clothing, then, carried not only pride but also irony and disillusionment in the revolutionary struggle.

Iran’s 1979 fashion shifts fit into a broader tapestry of international leftist iconography. The influence of global anti-colonial styles was explicit. Argentine Marxist Che Guevara’s image – beret and fatigues – had already circulated in Iran. Revolutionaries openly emulated his look, viewing themselves as heirs to 20th-century guerilla struggles . Meanwhile the Palestinian keffiyeh became a visible leftist sign. Iranian protest posters fused the keffiyeh’s pattern with slogans like “Death to imperialism, death to Zionism” , consciously linking Iran’s revolution to the Palestinian and Third World struggle. (Indeed, as one recent account notes, the black-white keffiyeh has become “ubiquitous and globally recognised” as a symbol of resistance .) These parallels show that Iranian leftist style did not emerge in isolation: it consciously echoed Latin American and Pan-Arab revolutionary fashion. In each case – Cuba’s olive uniforms, Algeria’s keffiyehs, Vietnam’s kaki – the left adopted a visual code of the people’s war, and Iranian activists took their place within that lineage.

Modern analysts of subculture emphasize exactly this communicative power of dress. As cultural theorist Lydia Mokdessi has observed, in the 21st century people’s style choices often “reflect prevailing… attitudes of… political resistance” and signal a commitment to leftist ideals . Iranian leftists of today are doing just that: they have revived the khaki jacket, Palestinian scarf, and plain mantu not as mere nostalgia but as explicit political messaging. Street images and online posts from recent protests frequently show young men and women wearing olive or brown jackets, keffiyehs, or other 1970s-style gear. In some circles even head-scarves or mantos are worn in deliberately plain fashion (and sometimes with anti-regime slogans) to signal both modesty and resistance. These fashion choices link back to Ali Shariati’s vision of an “authentic” Iranian modernity and Gharbzadegi’s call to shun Western consumerism . They also mirror global trends: for example, diaspora marches in 2022–25 often featured demonstrators in keffiyehs or red stars, consciously echoing international solidarity movements. In short, today’s leftists reuse 1979 symbols to assert continuity with the revolutionary era and with transnational anti-imperialist currents .

Why this revival now? Partly it is strategic: clothing remains a nonverbal shorthand for identity when speech is restricted. A khaki jacket or a scarf adorned with Rahbar slogans instantly communicates dissidence. It recalls the rhetoric of social justice from Shariati or Saedi, even if those names aren’t explicitly invoked. And it offers a way to redefine 1979’s legacy. The Islamic Republic emphasizes the clerical narrative of the revolution; by contrast, leftists reframe the apparel of that era in secular, socialist terms – downplaying religion while highlighting workers’ struggle and anti-Westernism. This redefinition makes sense in a global context where former religious symbols can be re-purposed (for example, Fanon argued that for colonial peoples clothing was a field of struggle, since “to destroy a society’s structure… one must first conquer the women…behind the veil” ; Iranian activists today might argue the reverse: that reclaiming clothing rejects the colonizer’s game).

In the end, Iranian leftist fashion today simply mirrors a universal lesson: dress is ideology. Antonio Gramsci argued that culture and “common sense” are battlegrounds for power, and clothing is a quintessential part of culture. As Frantz Fanon implied, garments like the veil or the jacket can be sites of liberation or domination. By repurposing the khaki, keffiyeh, and mantu of 1979, Iranian leftists enact their ongoing “war of position” through sartorial means. These revived outfits explicitly declare class solidarity, anti-colonial struggle, and a challenge to both the clerical regime and global capitalism. In this way, the style of 1979 remains a living language of resistance – every belt and scarf a word in the ideological discourse of Iranian leftism.