This article critically compares data-driven fashion trends – shaped by algorithms, big data, and predictive analytics – with organically emerging subcultures rooted in lived experience. Drawing on economic, anthropological, sociological, political, and philosophical perspectives, it surveys historic subcultural fashion movements (e.g. zoot-suiters, punk, hip-hop) alongside the rise of algorithmic forecasting (e.g. WGSN, AI-driven buyer tools). We examine the impact on authenticity, creative autonomy, and cultural production, invoking theorists like Debord, Benjamin, Bourdieu, Hall, Butler, and Sontag. The analysis focuses on Iran: how underground and regional dress (such as Southern/Bandari styles, Kurdish attire, and gender-fluid aesthetics) resist or adapt to global capitalist pressures and digital homogenization. In particular, Susan Sontag’s insights on camp and style inform our reading of the Tehran-based collection “Glamour of Bandar.” We argue that while algorithmic commodification tends to homogenize fashion (as Debord’s spectacle and Benjamin’s “aura” would predict), organic subcultures – by definition sites of identity and resistance – continually reinterpret heritage. In Hall’s terms, identities are “becomings” shaped by history , and subcultural styles exemplify this “continuous ‘play’ of history, culture and power” . Ultimately, we suggest that data-driven and grassroots forces remain in tension: the former optimizes market predictability, the latter asserts creative autonomy and local meaning.

In modern capitalism, fashion exists largely as spectacle: as Guy Debord observed, “all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles… Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation” . In fashion terms, this means styles often circulate as curated images and data points – hashtags, likes, and sales figures – rather than as embodied cultural practices. Indeed, today’s trendmaking is increasingly techno-driven. For example, Vogue Business reports that trend forecaster WGSN has introduced a “Fashion Buying” platform collating runway, e-commerce, and social-media data into AI models that predict category demand up to two years in advance . Similarly, industry analyses note that fast-fashion leaders like Zara and H&M “are turning to artificial intelligence to help them predict tomorrow’s trends… to stay ahead of the curve” . These tools mine sales and social data to schedule production and allocate inventory (e.g. WGSN’s TrendCurve AI uses Instagram/TikTok indices ). The stated goal is efficiency (reducing unsold stock, matching supply to demand), but critics ask: do such top-down forecasts undermine the creativity and surprise that once drove style? If algorithms simply bake in last season’s data to forecast next season, the scope for genuine novelty could shrink.

By contrast, fashion subcultures historically emerged from everyday practice, locality, and identity. Iconic youth movements – from 1940s Zoot-suiters to 1970s punks, goths and hip-hop crews – developed their own styles through bricolage of materials and symbols. Anthropologist Dick Hebdige notes that subcultural style is inherently contested: “the meaning of subculture is… always in dispute, and style is the area in which the opposing definitions clash with most dramatic force” . In practice, youth drew on whatever they could find to make identity claims. In mid-century America, for example, the Zoot Suit (a flashy ensemble with wide-legged trousers and broad shoulders) became a symbol of ethnic pride and defiance among Black and Latino youth. As a PBS historian writes, it “represented a powerful evolution of style, from the desire to be seen to the desire to be politically heard” . By challenging wartime austerity (and later flaring into race-riots), zoot suits showed how marginalized communities used dress to protest. Decades later, British punks explicitly scorned mainstream fashion. As Hebdige describes, subcultural style often starts as “a crime against the natural order” and can culminate in “a gesture of defiance or contempt… [that] signals a Refusal” . Punk youth shredded ordinary clothes, safety-pinned T-shirts, and dyed their hair into Mohawks – a DIY attack on polished norms. In doing so they created a coherent identity of resistance. Similarly, early hip-hop and B-boy cultures in 1980s New York remixed athletic streetwear into new style codes. Tracksuits, sneakers, and gold chains signaled community solidarity and urban identity. These fashions, like punk before them, were grassroots: ethnographic accounts emphasize that hip-hop style was made by young people themselves, not by runway designers. Social theorist Alan Warde notes that, in Bourdieu’s terms, shared tastes “classify and classify the classifier” – meaning youth styles both unify insiders and mark difference from outsiders . In sum, historic subcultures exemplify how style can emerge from the “play of history, culture and power” , encoding group meanings that conventional trend forecasting tends to overlook.

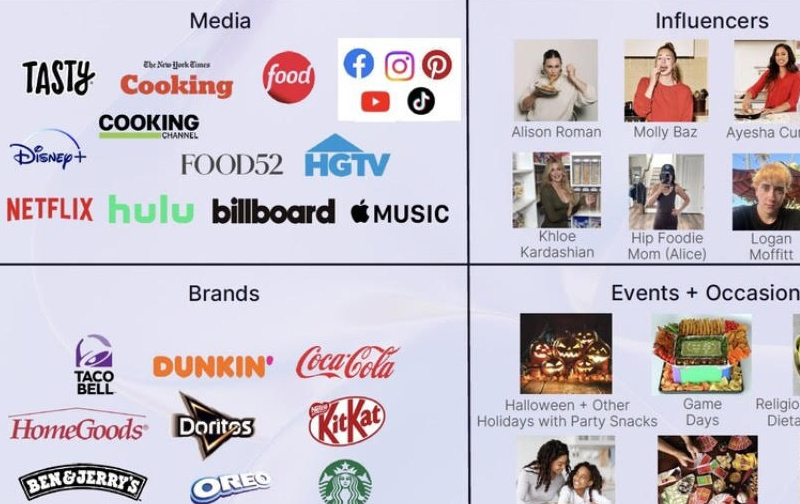

The last decade has seen this organic process give way to data-driven planning. Trend agencies and brands now feed vast amounts of information into predictive models. For instance, WGSN’s TrendCurve AI “pulls e-commerce data… along with runway data and a social index” to output the “percentage of the assortment that [an] item or category should represent,” forecasting up to two years ahead . Fast-fashion retailers likewise parse online search and purchase signals. A 2023 industry report notes that H&M, Zara and others deploy AI to “predict tomorrow’s trends… [and] understand what customer demand will look like” . Social media sites amplify this datafication: viral images on Instagram or TikTok are scraped to spot emerging patterns (colors, hashtags, street styles) which then feed corporate planning. In effect, a brand’s design team can see in advance which shade of neon or which silhouette is “trending” in real time.

On one hand, this can make fashion supply more responsive. Better forecasting may reduce waste and overproduction (a major industry concern). On the other hand, it blurs the line between producer and consumer: rather than designers leading, consumers’ aggregated behavior starts to dictate what will be designed. Data-driven design may standardize aesthetics. As one critic asks, when algorithms dictate the “right” mix of products, do companies still need imaginative curation? The Vogue Business analysis raises this question: “at what point does tech impede on the art of curation?” when buyers follow AI guidance . We can frame this technically: if every label uses similar data, market outcomes converge. The diversity of style shrinks into model outputs. Thus, algorithmic forecasting tends to compress fashion into statistics. This contrasts with subculture-driven fashion, which thrives on novelty and surprise rooted in context.

The shift toward data-driven fashion raises deep questions about authenticity and cultural authority. Walter Benjamin’s notion of the aura is instructive: he argued that mechanical (and digital) reproduction devalues an artwork’s unique presence, noting that “even the most perfect reproduction… is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence” . Fashion under algorithms is analogous: a clothing trend reproduced en masse and diffused online loses its original context. When Zara churns out a coat inspired by, say, Japanese street style, the coat’s “authentic” link to community is diluted. Bourdieu likewise saw fashion as social power: he writes that “taste classifies and classifies the classifier,” functioning as “a weapon for drawing social distinctions” . In an algorithmic regime, such distinctions risk becoming opaque: if everyone’s taste data is pooled, the tools may erase the very class or countercultural codes Bourdieu describes.

Guy Debord’s spectacle theory also applies: the spectacle reduces social life to representations governed by capitalist logic. In Debord’s words, modern production turns reality into “an object of mere contemplation” . If every style gesture is instantly photographed and sold, fashion becomes part of the spectacle itself. Indeed, Zara or H&M appear to live Debord’s model by turning trends into commodities in a self-reinforcing spectacle.

By contrast, cultural theorists like Stuart Hall emphasize the fluid, contested nature of identity. Hall argues that cultural identity “belongs to the future as much as to the past” – it is a matter of “becoming as well as of being” . Fashion can be a field of identity negotiation. Under data-driven design, however, identity becomes something to be segmented and monetized. Judith Butler’s insight – that “gender is not something you are, it’s something you do through repeated actions” – reminds us that style choices enact identity. Subcultural fashion often disrupts these norms (e.g. punks mixing fem/masc symbols or contemporary queers in Iran styling their hair and clothes freely). Corporate trend models, which assume stable consumer categories (men’s vs. women’s, etc.), may not accommodate such fluid enactments.

Susan Sontag’s work on aesthetics highlights another dimension. In “Notes on ‘Camp’” she observes that camp is the “love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration… the triumph of the epicene style” , and that “Clothes, furniture, all the elements of visual decor… make up a large part of Camp” . This suggests that fashion itself can be a form of critical play – clothing can be worn ironically or extravagantly to critique norms. The Tehran collection “Glamour of Bandar,” for example, draws on camp-like excess (bright patterns, theatrical silhouettes) in order to question authenticity. Such aesthetic rebellion runs counter to the data-driven ideal of measurable, rational fashion. In Sontag’s terms, camp style flouts the idea of originality and instead celebrates simulacra – something Baudrillard also noted about our info-saturated era. Thus, data-driven fashion (content without style) and camp aesthetics (style without conventional content) stand in stark opposition.

Iran’s fashion scene provides a striking case of these dynamics. Despite strict dress laws since 1979, Iranian youth continually appropriate and reinvent style. By the late 2010s, observers noted that Iranian women “were rocking bright colors and embroidered pieces… using their fashion choices to assert their independence and identity” . Social-media–fluent young people post secret streetstyle photos showing loose scarves, ripped jeans, or slogan tees in vibrant hues. One Independent photographer captured a woman in a Calvin Klein shirt and flowing skirt, her body and hair hidden only by the mandated black chador. This image epitomizes “the duality – of personal style and state-sanctioned conservatism” . In other words, even as authorities enforce conformity (jailing women for “bad hijab”), individuals quietly subvert it with color and form.

Hall’s notion of identity-as-becoming resonates strongly: contemporary Iranian style identity cannot be pinned to a fixed “authentic” Iran. As Hall writes, identity is constituted by both sameness and “points of deep and significant difference” through history . The Iranian case shows this vividly: each generation negotiates state ideology, global influence, and heritage anew. Social media accelerates this process – a bold look in Tehran can inspire imitations regionally, yet online visibility also attracts state censors. Thus, digital culture is double-edged: it lets local styles circulate beyond their borders, but it also exposes them to exploitation. Some global brands have started appropriating Persian patterns (e.g. a Zara collection once featured prints resembling chador designs), often without context. In response, grassroots Iranian designers and stylists emphasize local narrative: they embed poetry, ethnic symbols, or even political slogans into clothes, reclaiming authorship. Ultimately, the Iranian example illustrates how subcultures can adapt global trends to local resistance. They use the very tools of the spectacle (Instagram, YouTube) to spread anti-spectacular messages – humor, irony, and a reminder that “taste” is not just data to be mined, but a lived code.

In summary, the fashion industry today sits at the crossroads of techno-capital and cultural heritage. Data-driven trend forecasting (via WGSN, AI, Big Data) pushes brands toward hyper-efficient, predictive planning, effectively making style a branch of algorithmic commodity. This process, in Debordian terms, turns even subculture into spectacle – everything is transformed into an image and a statistic. According to Benjamin and Bourdieu, this risks stripping garments of their unique aura and turning taste into a less meaningful uniform . On the other hand, organic subcultures remind us that fashion can be an active cultural practice. Drawing on Sontag and Hall, we see that style can subvert norms through artifice and become a site of identity‐work . The “Glamour of Bandar” collection exemplifies this: it intentionally mixes kitsch and elegance (à la Sontag’s camp) to challenge both Western and local fashion expectations.

For global fashion experts and brands, the lesson is that authenticity cannot be fully engineered. Technical models may capture macro‐level trends, but they tend to overlook the micro-level meanings of dress that subcultures create organically. As Iranian subcultures show, local context and resistance imbue clothing with a depth that no dataset can fully replicate. Therefore, the fashion industry must learn from subcultures: to remain sensitive to context, to allow flexibility, and to treat culture as participatory rather than passive. Otherwise, as Hall warned, reducing culture to data would freeze identity into fixed templates, ignoring the ever-changing “play” of human creativity . In the end, fashion’s true innovation may lie not in perfect forecasts but in the continuous, unruly dialogues between the data-driven world and the subcultural worlds that spring from “the bottom up.”