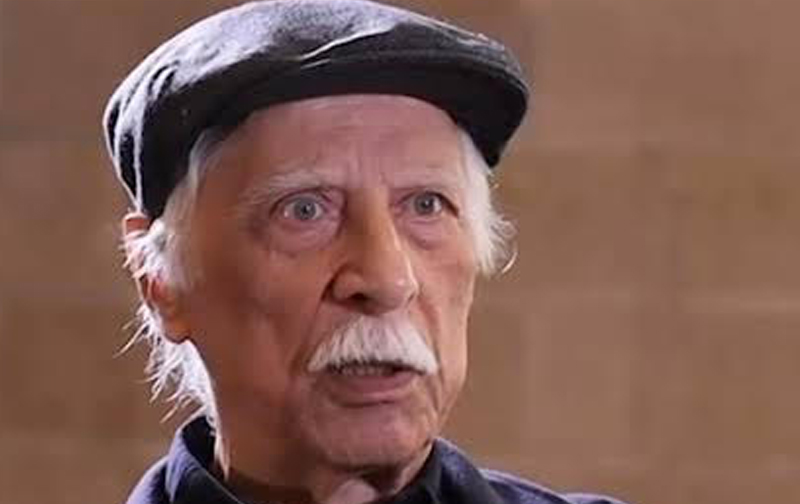

Bahram Beyzai (born 1938) is a renowned Iranian filmmaker, playwright, theatre director, and scholar whose career spans over six decades. Often hailed as the “Shakespeare of Persia,” he has profoundly influenced Iranian arts by blending ancient mythology with modern narrative forms. Beyzai emerged as a leading figure in the Iranian New Wave cinema of the late 1960s–70s, introducing innovative storytelling and visual styles that challenged mainstream norms. Simultaneously, he reinvigorated Persian theater through groundbreaking plays and seminal research, such as his authoritative book Theatre in Iran (1965), which reconstructed the rich heritage of Iranian performance traditions. His works—both on stage and screen—are distinguished by a poetic interweaving of history, mythology, and social critique, often centered on marginalized voices and strong female protagonists. Forced into exile after the 1979 Revolution due to censorship, Beyzai continued his artistic and academic pursuits abroad, notably at Stanford University since 2010, where he has lectured on Iranian cinema and theater. This article offers a comprehensive bilingual examination of Beyzai’s life and legacy, covering his early life and influences, contributions to theater and film, thematic and philosophical frameworks, and his lasting impact on Iranian cultural identity and the Persian language. Through an academic yet poetic lens, we explore how Beyzai’s fusion of mythic imagination with modern form has created a body of work that resonates with both Iranian and global audiences.

In the landscape of contemporary Persian art and literature, Bahram Beyzai stands out as a polymath: a filmmaker, playwright, theater director, screenwriter, and historian whose influence is virtually unparalleled. Born into a literary family in Tehran in 1938, Beyzai was imbued from childhood with the rich currents of Persian poetry, storytelling, and intellectual inquiry. Over the ensuing decades, he became a central figure in reformulating Iranian performing arts, deftly translating Iran’s enormous cultural heritage into modern forms. His career coincided with pivotal eras of Iranian history—post-World War II tumult, rapid modernization under the Pahlavi regime, the seismic shift of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, and the challenges of diaspora—which together shaped the thematic depth and urgency of his work. As a result, Beyzai’s creative output is “satiated with images of cultural transition and suppression,” persistently questioning official narratives of nationhood and giving voice to the silenced chapters of history.

Beyzai’s significance lies not only in the volume of his work—comprising over 70 plays, screenplays, books, and countless essays—but in its unusual breadth of genres and scholarly depth. He is celebrated as a pioneering New Wave film director and as a preeminent playwright often considered the greatest in the Persian language. Indeed, many refer to him as “The Shakespeare of Persia,” underscoring his status as a virtuoso of Persian letters and drama. His films, such as Downpour (Ragbar) (1972) and Bashu, the Little Stranger (1986), broke new ground in Iranian cinema with their innovative narratives and symbolism, garnering international awards and even being voted among the best Iranian films of all time. Concurrently, from the 1960s onward, his stage plays and theoretical writings rejuvenated Iranian theater by reconnecting it with indigenous roots—myth, epic, folklore—and infusing it with experimental forms inspired by both Eastern and Western traditions. Beyzai headed the Theater Arts Department at Tehran University and authored Theatre in Iran, the first comprehensive study of Iran’s dramatic heritage, cementing his reputation as a scholar-artist who bridges past and present.

This introduction sets the stage for a detailed exploration of Bahram Beyzai’s life and work. Following sections will delve into his early life and family background, highlighting how a childhood steeped in poetry and storytelling kindled his fascination with mythology and history. We will examine the profound influence of Persian myths and classical literature on his artistic vision, as well as his formative efforts to forge a distinctly Iranian theater and cinema that could “modernize without cultural alienation”. Beyzai’s contributions as a playwright, director, and theorist of theater will be discussed, alongside an analysis of his landmark films—their directorial style, narrative innovations, controversies with censors, and critical reception at home and abroad. Attention will be given to his life in exile and role as a teacher at Stanford University, reflecting on how displacement impacted his perspective yet also expanded his global reach. Furthermore, we will explore recurring themes in Beyzai’s oeuvre—identity, time, history, politics, memory, gender, and symbolism—and how these are expressed through a rich tapestry of images and allegories. Comparisons will be drawn between Beyzai’s philosophical and artistic frameworks and those of world-renowned intellectuals like Nietzsche, Jung, Brecht, Tarkovsky, and Rumi, revealing resonances between his work and global currents of thought. Finally, the article will consider Beyzai’s legacy: his influence on subsequent generations of Iranian filmmakers and dramatists, his contributions to the Persian language and cultural identity, and the enduring relevance of his mythopoetic vision in contemporary discourse.

Bahram Beyzai was born on December 26, 1938 in Tehran, Iran , into a culturally rich family that profoundly shaped his future artistic path. His father, Ne’matallah Beyzai (pen-name “Zokā’i”), was a respected poet, literateur, and anthologist. The Beyzai lineage boasts several notable poets and scholars: Beyzai’s paternal uncle, Adib Beyzai, was regarded as one of the great poets of 20th-century Iran, and both his grandfather and great-grandfather were also celebrated men of letters. On his mother’s side, young Bahram was influenced by strong, educated women – his mother and grandmother – who were passionate storytellers, versed in folklore and classical poetry. They regaled him with dastan (legends) and folk tales from an early age, instilling in him an enduring love of Iranian mythology and storytelling traditions. Beyzai’s family roots extend to the town of Aran o Bidgol near Kashan, and notably, some of his forefathers there were master performers of Ta’ziyeh, the traditional Persian passion-play ritual. Thus, from the outset, Beyzai’s world was suffused with literature, myth, and indigenous theatrical practices – a fertile cultural soil that would later nourish his creative work.

From a young age, Beyzai demonstrated an independent spirit and an eagerness to immerse himself in the arts. As a teenager attending Darolfonoon High School in Tehran, he grew increasingly disinterested in the rote formal education of the time. Instead, he often skipped classes to watch movies at local theaters, as Iran in the 1950s was experiencing a boom in popular cinema. This adolescent cinephilia not only fed his imagination but also provided a refuge: Beyzai later reflected that during the politically tense 1950s, going to the movies offered him an escape from the violence and intimidation he witnessed in school and society. By age 17, he was voraciously devouring films and visual arts, as well as reading plays and literature outside the curriculum. At the same time, he began writing his earliest plays while still in high school. Notably, he penned two historical dramas in these late-teen years, works that signaled his lifelong penchant for history and legend as source material.

After finishing school, Beyzai did not follow a conventional university path in a single discipline; instead, he pursued self-directed studies and research. In 1959, at around age 20, he undertook intensive research into traditional Persian theater forms and epics. Beyzai spent the years 1959–1961 deeply exploring Iran’s pre-Islamic culture, Persian mythology, and classical literature. He was driven by a desire to discover an authentic language for Iranian art that could speak to contemporary issues while remaining rooted in Iran’s cultural heritage. During this period, he delved into ta’ziyeh (ritual passion plays commemorating martyrs), naqqāli (dramatic storytelling by itinerant bards), kheimeh-shab-bazi (traditional puppet theater), and ru-howzi (improv comic theater). Beyzai became convinced that these indigenous dramatic forms, largely marginalized by both the elite and academia at the time, held the key to creating a modern Iranian theater that wasn’t merely imitative of Western plays. By studying these arts and the Shahnameh (Iran’s national epic by Ferdowsi), Persian folklore, and even Pahlavi (Middle Persian) texts, he gained a deep appreciation for Iran’s mythic imagination and how it could be revived on stage and screen.

It was also in his early twenties that Beyzai joined the Iranian intellectual scene: in 1958 he became involved with Farrokh Ghaffari’s Tehran cine-club, one of the first venues where art films and world cinema were shown in Iran. Exposure to international classics and modernist films through the cine-club broadened his cinematic vocabulary and introduced him to global auteurs. Simultaneously, he associated with the emerging theater troupes of the era, such as the National Arts Guild (Goruh-e Honarhaye Melli), which staged plays with an Iranian sensibility. These experiences solidified Beyzai’s twin passions for cinema and theater, and by the early 1960s he was actively writing essays on Iranian performance traditions and scripts for the stage. In fact, at just 19, he wrote a play titled Arash (1958) re-imagining the legendary archer from Persian myth – a direct response to a modern epic poem “Arash-e Kamangir” by Siavash Kasraei. This youthful work is emblematic of Beyzai’s instinct to reclaim myth for modern purposes: in the original legend, Arash is a willing hero who sacrifices himself for his people, but Beyzai’s interpretation cast Arash as a reluctant ordinary man cornered by circumstances into heroism, thereby making the myth speak to contemporary ideas of the “common man” as hero.

Beyzai’s early exposure to political and social upheaval in Iran also left an indelible mark on his consciousness. He came of age during the tumultuous post-war decade: he was just a child when foreign armies occupied Iran (1941–46), and a teenager during the nationalist fervor and subsequent CIA-backed coup of 1953. His family’s Bahá’í faith (his father had converted to the Bahá’í religion) meant they faced discrimination in the 1950s when a wave of anti-Bahá’í sentiment and propaganda swept the country. As a result, the young Beyzai witnessed first-hand what it meant to be marginalized in one’s own homeland – an experience that fostered in him a lifelong empathy for the oppressed and an awareness of the corrosive effects of dogma and tyranny. One scholar describes how these early encounters with injustice gave Beyzai a “standpoint of the marginalized,” sharpening his insight into power dynamics and fueling his determination to speak for those denied a voice. This sensitivity later permeated his creative work, where heroes are often outsiders or underdogs, and where the critique of authoritarianism and fanaticism is woven through allegory and symbolism rather than blunt politics.

In summary, Beyzai’s formative years combined a rich cultural inheritance with rebellious self-education. By the time he entered his mid-twenties, he had already laid the groundwork for a new kind of Iranian art. He had acquired encyclopedic knowledge of Persian myths and traditional theater, published articles in literary journals, and written several plays that reinterpreted ancient legends through a modern lens. He was also connected to a circle of young Iranian writers and artists (such as contemporaries Akbar Radi and Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi) who, like him, sought to create original works true to Iranian identity – these figures would soon be recognized as founders of the “Iranian New Wave” in theater and literature. Beyzai’s early life, thus, set the stage for his emergence as a visionary artist: one rooted in the memory of the past yet boldly innovating for the future.

Central to Bahram Beyzai’s artistic vision is a profound engagement with Persian mythology and classical literature. From his earliest writings to his later films and essays, Beyzai has continuously mined Iran’s ancient epics, folklore, and mystical poetry for themes, symbols, and narrative structures, reworking them into new forms. This conscious return to myth was, for Beyzai, both an aesthetic choice and a cultural mission: he sought to revitalize the collective memory of the Iranian people through art, believing that the timeless wisdom of legends could shed light on contemporary issues. His approach was not one of uncritical nostalgia or mere retelling; rather, he employs myth in a revisionist and critical mode, often giving voice to characters or perspectives ignored in the original tales. In doing so, Beyzai creates what one might call a modern “mytho-poetic” theater and cinema, where each work resonates on multiple levels – as a story, as an allegory with political or social subtext, and as a commentary on the myths themselves.

One of Beyzai’s earliest endeavors in this realm was his aforementioned play Arash (1958). The play reimagines the legend of Arash the Archer, a heroic figure from Iranian myth who sacrifices his life by shooting an arrow to demarcate Iran’s borders. While the traditional story (recorded by medieval sources) casts Arash as a preordained savior, Beyzai’s version presents him as an ordinary young man pressed into heroism by circumstance. By doing so, Beyzai transforms the myth: Arash becomes an existential hero, choosing self-sacrifice not out of divine destiny but from personal resolve when faced with oppression. This aligns with Beyzai’s broader tendency to democratize heroism in myth—making heroes out of common folk, and conversely, scrutinizing legendary heroes to reveal their human flaws. Similarly, in his play Azhdahak (written 1959, later published 1966), Beyzai tackles the myth of Zahhāk (the dragon-king in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh). In the original epic, Zahhāk is a vilified figure who grows snakes on his shoulders and devours the brains of youths. Beyzai, however, wrote Azhdahak as a dramatic monologue from Zahhāk’s perspective, effectively echoing the unheard voice of the “demonized” king. By letting Zahhāk speak, the play examines how fear and marginalization can turn a person into a monster in the eyes of society. The snakes on Zahhāk’s shoulders in Beyzai’s retelling symbolize the hate and violence imposed on him, suggesting that tyrants are often the product of a cycle of brutality – a bold and nuanced interpretation that invited audiences to reconsider a black-and-white legend.

Beyzai’s fascination with mythology also led him to scholarly research on the topic. He authored essays tracing the origins and transformations of famous Persian legends. Notably, his monograph “Where is Hezar Afsan?” (Hezār Afsān kojāst), published in 2012, investigates the roots of the Thousand and One Nights (known in Persian as Hezār Afsān or Alf Layla wa Layla). In this study, Beyzai examines how this compendium of stories – often thought of as Arabic due to its current form – actually has deep connections to ancient Persian and Indian storytelling traditions. He connects the Nights to the Persian epic Shahnameh and other pre-Islamic Iranian sources, arguing for a reevaluation of cultural ownership and influence. Similarly, his book “Seeking the Roots of the Ancient Tree” (2003) delves into the mythic and literary roots of Iranian legends, highlighting how elements of these tales appear in various historical texts. Beyzai’s research underscores a key belief of his: that Iranian culture possesses a continuous narrative thread from antiquity to modern times, one that artists can draw upon to create works with deep cultural resonance.

In his cinema, Beyzai’s mythological bent is often evident through symbolism and narrative archetypes. His film The Stranger and the Fog (1974) is a striking example. It unfolds like a cryptic fable: a mysterious man washes ashore in a village engulfed by fog, with no memory of his past, as ominous figures soon come searching for him. The film’s atmosphere of uncertainty, ritualistic staging, and timeless setting give it a mythic quality—critics likened the pervasive fog to a “metaphysical presence” akin to the sea in Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice or the Zone in Stalker, symbolizing an inescapable fate or history that weighs on the characters. The Stranger and the Fog operates on the level of myth (the stranger as a archetypal figure of the outcast or the eternal wanderer) and on the level of social parable (hinting at themes of collective guilt, memory, and otherness). Beyzai deliberately obscures the specific time and place, creating a mythic time that, as one analysis noted, “obscures time, place, and motive” to achieve a universal allegory. The result is a film that feels like part-dream, part-ancient legend, yet it subtly critiques how communities treat the outsider and how the past haunts the present.

Another film, Ballad of Tara (Cherike-ye Tara, 1979), explicitly brings a historical myth into a modern context. In this story, a young widow in contemporary northern Iran finds a centuries-old sword and then encounters the ghost of an ancient warrior seeking to reclaim it. This surreal premise allowed Beyzai to juxtapose modern life with the specter of Iran’s past – literally, as Tara debates with the ghost about war and purpose. The film, rich with allegory, implies questions about the cycles of violence and the inheritance of history. Notably, Ballad of Tara draws on motifs from Persian myth (a magic sword, an ethereal visitor) to comment on the present, a hallmark of Beyzai’s style. The movie was completed on the eve of the 1979 Revolution and unfortunately banned by the new regime, who were wary of its ambiguous messaging; it remained unseen by the public for many years. Nevertheless, Ballad of Tara has been studied for how it exemplifies Beyzai’s melding of myth with social critique – Tara can be seen as a symbol of Iran itself, caught between an oppressive historical legacy (the warrior demanding the sword) and the need to move forward in peace.

In theater, Beyzai’s mythological influence is equally pronounced. He wrote a series of plays known as the “Eastern myths” cycle, including works like Siyavash Khani (a play based on the mourning recitations of Prince Siyâvash from the Shahnameh) and Marg-e Yazdgerd (Death of Yazdgerd, 1979) which is set in the aftermath of the assassination of the last Sassanian king, Yazdgerd III. In Death of Yazdgerd, Beyzai uses a historical-mythical event as a backdrop for a philosophical inquisition: a Miller, his wife, and daughter are accused of killing the fugitive King, and through their shifting testimonies, the play examines truth, power, and guilt in a manner reminiscent of Kurosawa’s Rashomon (itself drawn from Japanese lore). The setting is historical, but the treatment is highly stylized and symbolic – characters become embodiments of concepts like Justice, Greed, or Innocence. Death of Yazdgerd reads as a metaphor for the corruption and chaos at the end of a dynasty, and some have interpreted it as Beyzai’s comment on the contemporary revolution without ever referencing it directly (the fall of a king presaging the fall of the Shah). This play, filled with ritualistic dialogue and even moments of dance and music, underscores Beyzai’s commitment to what he calls “the ritual roots” of theater. He often cites that Eastern theatrical traditions – from Persian ta’ziyeh to Japanese Noh – treat theater as a semi-ritualistic act, a quality he consciously emulates. This ritualistic approach, combined with mythic subject matter, gives his stage works a uniquely immersive and reflective quality.

Beyzai’s use of classical literature is not limited to mythic epics; he also dialogues with Persian poetry and spiritual texts. For instance, he has referenced Jalal al-Din Rumi, the 13th-century mystic poet, as an inspiration for some of his symbolic imagery and understanding of narrative. While Beyzai’s works are not direct adaptations of Rumi’s stories, they share a mystical sensibility – the idea that reality has hidden layers, and truth is often conveyed through metaphor and paradox. In a way, Beyzai’s blending of fantasy and reality on stage reflects Rumi’s line: “The truth was a mirror in the hands of God. It fell, and broke into pieces. Everybody took a piece of it, and they looked at it and thought they had the truth.” Beyzai’s plays often present fragmented truths (multiple versions of an event, as in Death of Yazdgerd) and invite the audience to contemplate deeper meanings. Moreover, his emphasis on storytelling as an act of salvation echoes the framework of One Thousand and One Nights, where Scheherazade’s tales stave off death – a parallel to how Beyzai views cultural storytelling as a means of civilizational survival.

In summary, Persian mythology and literature are the lifeblood of Beyzai’s creativity. By reinterpreting myths like Arash, Zahhāk, or Siyâvash, he infuses his works with archetypal power while also questioning the chauvinistic or authoritarian tendencies of those myths (for instance, he often elevates female characters or commoners, subverting the male-hero dominance typical of epics). His films employ mythic symbols – fog, mirrors, swords, journeys – to trigger the audience’s subconscious associations, a technique reminiscent of Carl Jung’s idea of archetypes in the collective unconscious. Indeed, one could argue that Beyzai acts almost like a Jungian alchemist of storytelling, tapping into the deep symbolic reservoir of Persian culture to forge narratives that address the modern psyche. By intertwining the ancient and the modern, Beyzai ensures that the classical soul of Persian literature remains alive, continually re-sung and re-imagined for new generations.

Beyzai’s impact on Iranian theater is monumental. He is often credited with almost single-handedly dragging Iranian drama from a period of stagnation into a new era of innovation and self-awareness in the 1960s and 1970s. Before Beyzai and his contemporaries, Iranian theater was largely limited to either traditional folk performances not taken seriously by intellectuals, or Western-style plays that had been imported and translated. Beyzai revolutionized this landscape in three interrelated roles: as a playwright of original Persian plays, as a stage director who introduced new theatrical techniques, and as a theorist/scholar who researched and defined the history and aesthetics of Iranian theater.

As a playwright, Beyzai is unparalleled in modern Persian literature. He has written dozens of plays, many of which are now regarded as classics. His plays often draw from historical or mythical subjects but are executed with modern sensibilities and complex characters. For example, Sohrab’s Death (a script he wrote reimagining a tragic episode from the Shahnameh) or The Eight Voyage of Sinbad (which uses the familiar name of Sinbad to tell a wholly new parable) show his knack for leveraging known tales as scaffolding for exploring contemporary themes. Perhaps his most famous play is Death of Yazdgerd (1979) which we discussed earlier – it has been hailed for its bold form and content, weaving philosophy and suspense in a deeply Iranian idiom. Another celebrated play is Kalagh (The Crow, 1963, not to be confused with his later film of the same name in 1977), which is a stage drama blending realism with expressionistic elements to critique social norms (this was later adapted into the 1977 film). Beyzai’s scripts are known for their rich, poetic dialogue and strong dramatic structure. He often defies conventional endings, leaving the audience with open questions – an approach influenced by Brechtian epic theater in that it provokes the audience to think rather than giving neat catharsis. Indeed, critics have noted Brecht’s influence on Beyzai; like Bertolt Brecht, Beyzai sometimes breaks the “fourth wall” or uses theatrical devices to remind the viewer that what they are seeing is a constructed performance, thereby encouraging critical reflection rather than passive consumption. An example is the play Jana and Baladoor (2012, premiered at Stanford as a shadow play), where he uses puppets and shadow figures to retell a classical romance, consciously invoking the artifices of traditional theater as part of the storytelling.

Beyzai’s approach to character in his plays is also notable. He shunned the simplistic hero/villain dichotomy common in earlier dramas, instead writing nuanced individuals often caught in ethical dilemmas or social predicaments. Importantly, he brought women to the forefront of Iranian drama. In many of his plays, a female character carries the moral or intellectual weight of the story – a deliberate counter to the male-centric narratives of both traditional epics and modern patriarchy. Truths About Leila, the Daughter of Idris (1975, unproduced at the time but later published) is one such screenplay: it centers on a working-class young woman’s struggle for identity and independence in a hostile, male-dominated society. Beyzai wrote it in the mid-1970s, making it one of the earliest Iranian dramas to explicitly tackle the experience of women outside the domestic sphere. The play proved too far ahead of its time to be staged then – as the head of the state-run cinema agency objected to Beyzai’s choice of a non-glamorous actress and effectively canceled the production – but its text would later influence younger filmmakers (it’s noted that Asghar Farhadi’s 2016 film The Salesman carries echoes of Truths About Leila’s premise). Beyzai’s consistent championing of female perspectives in his writing earned him recognition as a proto-feminist voice in Iranian theater, in stark contrast to the stereotypical portrayals of women prevalent before. This feminist undercurrent in his plays dovetailed with his interest in myth: he observed that in folktales (unlike formal epics) women often play savior roles, and he leveraged that observation by creating modern folktales on stage where women assume central, empowered roles.

As a director of theater, Beyzai introduced new staging methods and revived forgotten ones. He was a great experimenter with form. For instance, he reintroduced choral narration and live music into plays, akin to Greek tragedy or Persian ta’ziyeh, to heighten the dramatic effect. In Siyavash-Khani, he incorporated traditional rhythmic chants and the presence of a morshed (a narrator figure in Persian passion plays) to create a bridge between modern drama and ancient ritual. In other productions, Beyzai used minimalist sets and stylized movements influenced by Eastern theater traditions. He was inspired by Japanese Noh and Kabuki, Indian Kathakali, and Chinese opera (all of which he studied), and he often fused these with Iranian elements. For example, his play The Story of the Panda Chan (an experimental work) used masks and highly choreographed movement in ways reminiscent of Oriental theater. Such cross-cultural pollination was pioneering in Iran’s theater scene, which had been rather proscenium-bound and text-heavy. Beyzai also championed the use of symbolic props and lighting to convey themes. A famous anecdote is how in a production of Marg-e Yazdgerd, he scattered flour on the stage to represent both the literal flour mill (the setting of the play) and a metaphorical field of souls or the passage of time. His stagings could be lavish when needed – he paid meticulous attention to costumes, often designing them based on historical research – but the spectacle was always in service of the story’s deeper meaning, not for mere ornamentation.

In 1968, Beyzai was among the founders of the Iranian Writers’ Association, a collective of intellectuals advocating for freedom of expression. This shows his commitment not just to creating art but to shaping the artistic community and defending its rights. He also co-founded the Center for Advanced Dramatic Arts in the late 1960s, and in 1972 he established a theater group called “The National Theater Group” (Goruh-e Melliat) which aimed to produce new Iranian plays. His leadership abilities led to his appointment as the Chair of Dramatic Arts at the University of Tehran’s Faculty of Fine Arts in the 1970s. In that capacity, Beyzai mentored a generation of students, updated the curriculum to include Iranian performance traditions, and directed university theater festivals. Those years were a renaissance for Iranian theater, and Beyzai was at the helm.

However, the Islamic Revolution of 1979 dramatically disrupted Beyzai’s theater work. Seen as an icon of secular, intellectual art, he came under suspicion by the new regime. Shortly after the Revolution, Beyzai was forced to resign from his university position, and many of his plays were banned or censored by the Islamic authorities. Public theater itself went through a dark period in the 1980s due to war and ideological strictures. Beyzai, unwilling to bow to censorship, effectively stopped staging plays in Iran after 1979. A notable exception was in 1995 when he was briefly permitted to stage Death of Yazdgerd in Tehran – a triumphant but rare return to theater that played to packed audiences hungry for his work. After that, he again faced restrictions. It wasn’t until the late 1990s, during a relative cultural thaw, that two more of his plays were staged in Iran: Mosafere-e Vasl (“The Intersecting Journeys”) and Zan-e Neveshtan (“Woman of Writing”) in 1997 – staged simultaneously in two different halls of Tehran’s City Theater. In 2003, he staged A Night of the Thousand and First Night (Shab-e Hezar-o-yekom) in a four-sided theater configuration, experimenting with spatial dynamics and audience arrangement. In 2005, his play Māple, or The Day Passes (perhaps “Maple, ya Ruz Migozarad”) was produced in Tehran’s Vahdat Hall to great acclaim. These sporadic stagings showed that even after years of forced absence, Beyzai’s name could draw enthusiastic crowds, and his work remained as relevant as ever. But the difficulties persisted, and ultimately Beyzai emigrated in 2010, which effectively ended his direct involvement in Iranian theater inside the country.

As a theorist and historian of theater, Beyzai has left an enduring scholarly legacy. At just 26 years old, he published Namayesh dar Iran (Theatre in Iran, 1965), which was the first comprehensive study of the history of Iranian theater from ancient times to the modern era. This book is still considered a foundational reference in the field. In it, Beyzai meticulously catalogued and analyzed Iran’s indigenous theatrical forms – from religious processions and storytelling traditions to puppetry and comedic improvisations. He demonstrated that, contrary to a then-common belief, Iran did have native dramatic traditions long before the advent of Western influence. By outlining forms like ta’ziyeh, ru-howzi, sāye-bāzi (shadow play), and others, Beyzai argued for a continuous theatrical heritage that Iranian dramatists could be proud of and draw upon. This scholarship served not only academic interest but was directly linked to his creative goals: it provided a theoretical backbone for the kind of theater he and others were trying to create – one that was modern yet culturally rooted.

Beyzai didn’t stop with Theatre in Iran. He wrote extensively, including articles on Eastern vs Western theater (“East/West Theater” where he contrasts narrative performance traditions of Asia with the dramatic traditions of Europe), and essays like “Art and Identity” focusing on how performance reflects national identity. He has also penned analyses of literature and cinema, bridging disciplines. A notable aspect of his theoretical work is the concept of “performative and ritual roots” of drama, which he elaborates in essays and lectures. He posits that in traditional Eastern performances, storytelling, music, and movement are integrated in a way that was lost in the Western naturalistic theater – and he aimed to reintegrate those elements. This theory informed not only his plays but even his films, which often contain overt theatricality.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, when Beyzai was partially silenced as a practitioner in Iran, he continued to write and publish scholarly work – much of it outside Iran or underground. He wrote a research on Iranian narratives and their connection to other cultures (for example, drawing parallels between Persian naqqāli storytelling and Japanese Noh in a comparative study). His work Hezar Afsan and Ancient Tree mentioned earlier also tie into theater history because they trace how narrative performances evolved. In 2018 (while at Stanford) he even wrote “Namir-e No” (The New Mime) discussing the potential of mime and movement in Persian theater.

To sum up, Beyzai’s contributions to Iranian theater are multifaceted and far-reaching: Dramaturgy: He vastly expanded the repertoire of original Persian plays, often using Persian historical and mythological contexts to reflect on universal issues.

Stagecraft: He innovated theatrical techniques, merging traditional and experimental methods, and influenced stage aesthetics in Iran by demonstrating the power of minimalism and symbolism over pure realism.

Institution-building: He educated and inspired new talent through academia and theater groups, playing a direct role in forming a modern Iranian theatrical movement.

Theory and history: He documented and analyzed Iran’s theatrical past, giving future artists a sense of continuity and identity, while also critically engaging with global theater theory to push Iranian theater forward.

Taken together, these achievements justify Beyzai’s reputation as a towering figure of Iranian theater. As the British Academy recognized, he “played a central role in reformulating Iranian performing traditions” and helped modernize Iran’s theater with minimal cultural alienation. To this day, Iranian playwrights and directors are indebted to Beyzai’s vision, whether they directly emulate his style or build upon the foundations he laid. The living proof of his theatrical legacy is evident in the thriving of Persian playwriting and the ongoing interest in staging his works, both inside Iran (whenever possible) and among expatriate communities abroad.

While making his mark in theater, Bahram Beyzai also emerged as a trailblazer in Iranian cinema. He was a founding member of the Iranian New Wave film movement, a 1970s renaissance in Iranian cinema characterized by artistic experimentation, social commentary, and a break from formulaic commercial movies. Beyzai’s films are known for their intellectual depth, visual poetry, and engagement with themes of history and myth, setting them apart as unique cinematic works in Iran and internationally.

Beyzai came to cinema relatively “late” – his first feature film was released in 1972, when he was in his early 30s – yet he quickly established himself as a major director. His debut feature, Downpour (Ragbar, 1972), is often cited as one of the cornerstones of New Wave Iranian cinema. Downpour tells the story of a humble, educated schoolteacher (Mr. Hekmati) assigned to a rough neighborhood in southern Tehran and his gentle romance with a local girl against the backdrop of class tensions. Far from a simple drama, the film was lauded for its narrative innovation and subversion of mainstream tropes. Beyzai consciously upended the clichés of popular Iranian cinema of the time: instead of a macho action hero, his protagonist is a quiet intellectual; instead of melodramatic showdowns, the film offers subtle social observation and self-reflexive humor. In one famous sequence, Beyzai uses the framing of a broken mirror during a confrontation – a meta-cinematic touch that implies the old image of the “tough guy” must be shattered to allow a new hero (the teacher) to emerge. Critics at the time and since have praised Downpour as a “brilliant debut” that dared to say so much within one film. The film won awards at the Tehran International Film Festival in 1972, and decades later it was restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation (in 2011) because of its enduring importance. Downpour’s influence can even be traced to modern Iranian cinema: scholars note that aspects of its story and characters echo in later works, for instance in Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman (2016).

In the 1970s, Beyzai continued with an intriguing slate of films:

“The Stranger and the Fog” (Gharibeh va Meh, 1974): This was Beyzai’s second feature and is a dreamlike, allegorical film (discussed earlier in the context of myth) that further showcased his poetic style. It’s an “epic myth” on film, blending suspense with metaphysical overtones. Though perplexing to some audiences at release, it is now admired for its bold cinematography and use of archetypal imagery – water, fog, strangers – to explore fear of the unknown. Some contemporary critics didn’t know what to make of its unorthodox narrative and either dismissed it as too “intellectual” or attacked Beyzai with absurd allegations (e.g., linking the film’s mystery to his Baha’i background). Yet others recognized its brilliant use of color and motif, and in the long run it has been vindicated as a masterful work, especially after its restoration in 2023 by the Film Foundation.

“The Crow” (Kalagh, 1977): Not to be confused with his 1960s play, this film was part of what’s been termed Beyzai’s “city tetralogy” – four films where the urban environment and modern alienation are central. The Crow (1977) follows a journalist’s quest to find a missing girl in Tehran, evolving into a noir-tinged social critique. It is notable as the first of his films to feature an “intellectual woman” as a key figure, reflecting Beyzai’s aspiration to redefine women’s roles in Iranian society. The Crow uses mystery and even surreal time-traveling sequences through the city, making it an innovative blend of detective story and philosophical cinema. Upon release, Beyzai openly said in a press conference that a director’s duty was not to cater to popular taste but to elevate it – clearly reflecting his approach in The Crow.

“The Ballad of Tara” (Cherike-ye Tara, 1979): Discussed earlier, this film merges contemporary life with historical fantasy. Tara is a widow who encounters a ghostly past; the film’s unique tone – part realist, part folklore – and its commentary on war and heritage make it stand out. However, it faced the unfortunate fate of being banned before public release due to the Revolution. It only became available years later, but by then had attained a near-mythic status among cinephiles.

By the late 1970s, Beyzai was recognized as one of Iran’s top directors, alongside peers like Abbas Kiarostami, Dariush Mehrjui, and Masoud Kimiai. Unlike Kiarostami’s neorealism or Mehrjui’s social dramas, Beyzai’s style was more theatrical and symbolist, often requiring active interpretation by the audience. This occasionally put him at odds with both commercial expectations and political authorities, who preferred more straightforward messaging.

After 1979, Beyzai’s film career, like his theater work, was hampered by the new regime’s censorship. Yet he still managed to produce some of his most important films in the 1980s:“Death of Yazdgerd” (Marg-e Yazdgerd, 1981): Beyzai bravely adapted his own play into a feature film right in the wake of the Revolution. Filmed in an austere caravansary setting, it retained the intimate, stage-like quality of the play. The entirety of the film is a trial-like dialog among the Miller’s family and the military officers, grappling with existential and moral questions. The film’s release was delayed and it was not widely screened in Iran (authorities were uneasy with its complex, non-Islamic theme and possibly saw political allegory in it). However, it circulated in film festivals abroad, where it was praised for its originality. Death of Yazdgerd on screen is now studied for how Beyzai translated theatrical space to cinematic language – using inventive camera movements around the single set to create tension and focus. In a sense, it’s a precursor to later acclaimed one-location films (like Sidney Lumet’s 12 Angry Men or Asghar Farhadi’s The Salesman which also has a play within the film) but rooted in Persian narrative tradition.

“Bashu, the Little Stranger” (Bashu, Gharibeye Koochak, filmed 1986): This is arguably Beyzai’s most beloved film. Bashu tells the story of a young boy from southern Iran (dark-skinned and speaking Arabic due to being from the Khuzestan region) who is orphaned by the Iran–Iraq war and flees north, where he is found by a northern Iranian peasant woman and her children. The woman, Naii (played by Susan Taslimi), takes Bashu in as her own despite language and cultural barriers. The film is a moving tale of maternal love, the unity across ethnic divides, and the personal costs of war. Notably, Bashu was the first Iranian film to portray the Iran–Iraq war’s impact on civilians in a humanistic (rather than propagandistic) way, and it directly tackled issues of ethnicity and racism in Iran – the local villagers react to Bashu’s darker skin with suspicion, and Naii fiercely defends him, telling them essentially that humanity and kinship matter more than blood or origin. Because of these bold themes, Bashu also faced censorship: though completed in 1986, it was shelved by the authorities and only released in 1989, after the war ended. When it finally premiered, it was met with critical acclaim. In 1999, a poll of 150 Iranian critics and professionals rated Bashu the greatest Iranian film ever made. The power of Bashu lies in its simplicity and emotional truth – Beyzai shot it in rural Guilan with natural scenery, capturing everyday life with lyrical realism. At the same time, he imbued it with layers of meaning: Bashu’s journey is like a mythic quest for a new home, and Naii is portrayed almost as an earth goddess figure, communing with nature and spirits (in one scene she performs a protective ritual for her absent husband’s safety). This blending of realism and mysticism in Bashu is often compared to the work of directors like Satyajit Ray or even the spiritual humanism of Andrei Tarkovsky, although Beyzai’s voice remains distinctly his own.

During the late 80s, Beyzai also made a short film, The Journey (Safar, 1983), a mythically-charged story of two children which he later expanded elements of in his work, and another feature, Maybe Some Other Time (1988) – a complex narrative about an actress and the nature of reality and performance, which again plays with meta-theatrical elements.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, Beyzai, despite continuous obstacles, managed to direct two more feature films:

“The Travelers” (Mosaferan, 1992): A visually stunning and metaphorically rich film about a family awaiting the arrival of relatives for a wedding. Unbeknownst to the hosts, the travelers have died in a car accident en route, and the film intercuts between the waiting family (particularly the anxious bride) and the journey of the dead relatives’ souls. The Travelers uses devices like slow-motion and vivid color photography (still photography plays a role in the plot) to create a meditation on death and memory. In one famous scene, a large photograph of the traveling family, taken just before their trip, is developed in a darkroom and gradually reveals the truth of their fate – an elegant metaphor for how art (photography, cinema) captures and reveals hidden realities. This film further established Beyzai’s reputation as a poet of imagery, often likened to European auteurs. The use of supernatural or ghostly elements (the dead seeming to interact with the living) also cemented his style of magical realism on film.

“Killing Mad Dogs” (Sagkoshi, 2001): After a hiatus in filmmaking during the later 90s, Beyzai returned with this hard-edged social thriller set in the chaotic years following the war. Killing Mad Dogs follows a woman (played by Mojdeh Shamsai, Beyzai’s wife) who tries to unravel a financial corruption scheme that has landed her husband in jail – only to discover layers of betrayal. This film, though more grounded in contemporary reality than some of his others, still carries Beyzai’s signature focus on a strong female lead and critique of moral decay. It was interpreted as a biting allegory of post-revolution opportunism – the “mad dogs” being those who exploit chaos for personal gain. Despite its somewhat noir/thriller surface, Sagkoshi offers a commentary on gender (the lone woman’s struggle in a predatory male world) and truth versus deceit, linking it to Beyzai’s perennial themes. The film faced some initial resistance but was eventually released and received a warm welcome from critics and audiences in 2001. It turned out to be Beyzai’s last feature film made in Iran; the success of Sagkoshi – both critical and in art-house circuits – underlined the tragedy that a filmmaker of his caliber had to struggle so much to realize projects.

Directorial Style: Beyzai’s style is often described as a blend of realism and symbolism – what one writer called “a mixture of realism and expressionism”. Visually, he employs carefully composed shots, long takes, and a deliberate pace that allow scenes to breathe and the viewer to contemplate the images (earning him comparisons to Tarkovsky’s meditative pacing). He is known for making ordinary settings feel mythical – for example, the village in The Stranger and the Fog feels suspended out of time, or the house in The Travelers becomes a liminal space between life and death. He achieves this through cinematography (often working with great DPs like Mehrdad Fakhimi and Amir Naderi early on) that emphasizes atmosphere – using fog, mirrors, or contrasting light and shadow as visual metaphors.

Narratively, Beyzai’s films frequently forego linear, plot-driven structures in favor of character-driven and thematic structures. He isn’t afraid of ambiguity; he’d rather leave a question open than force a pat conclusion. This ties to his belief, mirrored in his theater, that audiences should be active participants in finding meaning. For instance, Bashu ends on a tender but unresolved note regarding the future, and The Stranger and the Fog leaves one unsure of the stranger’s ultimate fate, emphasizing the journey and the moral more than a clear resolution.

Another hallmark is self-referentiality and meta-narrative. Beyzai often alludes to the act of storytelling within his films. In Downpour, as mentioned, he literally breaks a mirror in the opening scene to symbolically break the cinematic illusion. In Maybe Some Other Time, the protagonist is an actress and the film blurs her identity with the roles she plays. This reflective quality indicates Beyzai’s awareness of cinema as an artifice – a “magic mirror” that can distort or reveal truth depending on how it’s handled. As one analysis of Downpour noted, by framing a tough guy versus an intellectual in the first scene and involving mirrors and frames, Beyzai “breaks the fourth wall to suggest the artificiality of social constructs”. This Brechtian influence in his film style sets him apart from most Iranian filmmakers, who tend(ed) to pursue more straightforward realism.

Recurring motifs: Across Beyzai’s films, one finds recurring visual and narrative motifs:

Mirrors, photographs, and recordings – symbols of truth, memory, or illusion. (e.g., the broken mirror in Downpour, the photo in The Travelers, the recorded voices/echoes in some scenes of Killing Mad Dogs).

The motif of journey or exile – characters often are on a journey (Bashu, Stranger and the Fog, Journey short film) or strangers in their environment (Mr. Hekmati in Downpour, the ghost in Tara, the journalist in The Crow who ventures into underworlds of the city). This reflects on identity and belonging, key themes for Beyzai who often highlights outsiders.

Children and orphans – symbolizing innocence and the future betrayed by adult society. Many of his works include orphaned or lost children (Bashu, the orphans in Journey, even Sohrab in the Shahnameh context). Orphanhood becomes a metaphor for the nation’s sense of lost identity or the aftermath of chaos (Bashu from war, Pahlevan Akbar in So Dies Pahlavan Akbar play lost as a child, etc.).

Strong women – as noted, heroines like Naii in Bashu, the women in Killing Mad Dogs, the bride in Travelers, or the many female leads in his plays, consistently break the traditional mold. On screen, this was highly unusual in Iranian cinema which, under both Shah’s era commercial films and early Islamic Republic restrictions, rarely allowed women such agency. Beyzai’s cinema therefore is often lauded for its feminist portrayal of Iranian women.

Symbolic use of color and elements – water, fire, earth, and wind show up with meaning. In Bashu, the lush green of the north contrasts with the dusty south; in Downpour, the rain is a cleansing and transforming force; in Stranger and the Fog, water and fog represent oblivion and memory. These elemental symbols align him with a poetic cinema tradition globally (Tarkovsky, Bresson, etc., whom he admires).

Critical Reception and Controversies: Beyzai’s films have consistently earned critical acclaim, both in Iran (among the intellectual and artistic circles) and abroad at international festivals. As noted, Bashu was voted the best Iranian film by critics, and many consider Downpour one of the finest debuts. Retrospectives of his work have been held, such as a complete screening of his films at the Vienna Film Festival in 1995, signifying global recognition. In 2004, he received a lifetime achievement award at the Istanbul International Film Festival. Scholars like Hamid Naficy have analyzed his contribution in the context of Iranian cinema’s evolution, often highlighting how Beyzai’s knowledge of theater and myth enriched his cinematic language beyond the visual – basically bringing a cultural depth that elevated Iranian cinema’s profile.

However, controversies did accompany his film career, mainly in the form of censorship struggles:

Under the Shah’s regime, while he had relative freedom, his films were sometimes deemed too intellectual. For example, some Iranian critics in the 1970s who expected more straightforward political allegories were frustrated by Beyzai’s layered approach. A critic complained The Stranger and the Fog was not overt enough in its politics – missing its subtle critique – demonstrating the perennial gap between Beyzai and certain ideologues.

Under the Islamic Republic, the challenges were greater. Ballad of Tara was banned (likely for its mystical content and possibly for showing a woman too freely associating with a “ghost man” without a chador in some scenes). Death of Yazdgerd was not publicly shown. Bashu was delayed for showing a woman without a headscarf at home (Naii often is just in her modest rural dress but not a formal hijab, which irked censors) and for highlighting ethnic diversity (some officials at the time did not want to confront racial prejudice so directly).

Maybe Some Other Time (1988) had a modern urban setting with an unveiled actress (since it’s about an actress, presumably shown in private or on stage unveiled) – this likely limited its domestic distribution.

Beyzai often had scripts that he could not get approved. For instance, a screenplay The Tale of the Shroud-Wearing Commander (Qesseh-ye Mir-e Kafanpush, 1979) and others written in the early 80s were published in book form but never filmed . Some of these works tackled war, tyranny, or historical analogies that the censors found too sensitive. Even Sagkoshi in 2001, though released, was reportedly trimmed in parts dealing with high-level corruption.

Ultimately, these obstructions played a significant role in Beyzai’s decision to leave Iran for the U.S. in 2010; he has stated in interviews that he could no longer tolerate not being able to make films or stage plays in his home country due to constant impediments. This is a point of both tragedy and testament: tragedy in that Iranian cinema lost an active genius on its soil, testament in that despite this, the films he did make have left a permanent imprint and are continually rediscovered by new audiences.

In conclusion, Bahram Beyzai’s film career, though not as voluminous as some (he made 10 feature films and a few shorts), is defined by quality, originality, and cultural resonance. He reformulated what Iranian cinema could be: scholarly yet accessible, deeply Persian yet universal in appeal. By integrating mythic and theatrical elements into film, he forged a cinematic language that expanded the idiom of Iranian cinema beyond realism into the realm of the metaphysical and philosophical. His works invite, even demand, active engagement and interpretation – a cinema that “makes you see the world differently”. This perhaps is Beyzai’s greatest contribution as a filmmaker: treating cinema not just as entertainment or even art, but as a mirror to society and self, one that might need to be shattered and reassembled to reveal truth.

In 2010, after a long and tumultuous career in Iran, Bahram Beyzai relocated to the United States – a turning point that marked the beginning of his life in exile. He was invited by Stanford University in California to serve as the Bita Daryabari Lecturer in Persian Studies. While the decision to leave Iran was undoubtedly painful, it opened a new chapter wherein Beyzai could share his vast knowledge with a global audience and continue creating art without the constraints that had plagued him in Iran.

At Stanford, Beyzai quickly became an invaluable member of the academic community. He began teaching courses on Iranian cinema, theater, and mythology, drawing upon his five decades of experience. Students marveled at having a living legend in the classroom – he wasn’t just lecturing from textbooks, he was the source of much of the knowledge on these subjects. His courses often covered topics like the history of Iranian theater (from ancient traditions to contemporary plays), the Iranian New Wave cinema (including analysis of seminal films, presumably even his own, albeit modestly), and thematic seminars on myth in art. According to Stanford’s program descriptions, Beyzai’s classes explored how Iranian art intersected with issues of national identity, politics, and global cinematic influences. Essentially, he was providing a bridge between Iran’s cultural heritage and world art for a diverse group of students.

Beyond formal teaching, Beyzai continued to create and stage works during his Stanford years – albeit on a smaller scale and often in workshop settings. For example:

In 2012, he directed Jana and Baladoor, a shadow-puppet play (mentioned earlier), which was performed by Iranian actors and students at Stanford. This experimental production allowed Beyzai to revive an ancient art form (shadow puppetry) with a modern twist, in a diaspora context.

In 2015, he staged Ardaviraf’s Report (Gozaresh-e Ardaviraf) at Stanford, working with an ensemble of Iranian actors. This play is based on a Zoroastrian myth (Ardaviraf’s journey to the other world), showing Beyzai still drawing on Persian mythology for artistic inspiration. The production was in Persian with English subtitles, playing to an audience of both expats and Americans – a truly bilingual, cross-cultural endeavor.

He also gave a number of public lectures and workshops, such as a series on “The Semiotics of Iranian Myths” at Stanford. In these, he shared insights into how Iranian folklore can be interpreted and reimagined, effectively continuing his life-long mission of keeping myth relevant.

In 2017, when Beyzai received an honorary Doctor of Letters from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, a special two-day workshop titled “In Conversation with Bahram Beyzaie” was organized – highlighting his international stature as a scholar-artist. There, academics (like Dr. Saeed Talajooy) and Beyzai himself discussed his work’s significance in reformulating Iranian drama and cinema. Such events reflect his global reputation: universities and cultural institutions around the world recognize Beyzai as a giant of Persian arts.

Life in exile also meant Beyzai could collaborate and engage freely with other world artists and communities:

He attended film festivals, retrospectives (like one in Berkeley, California) and often appeared for Q&A sessions.

His presence in the US allowed him to reach the Iranian diaspora; for instance, when Mojdeh Shamsai (his wife, a renowned actress) and he mount a play or film screening in California, it becomes a cultural reunion for Iranian-Americans and students alike, reinforcing cultural identity through art.

Additionally, he gained more exposure in Western media and scholarly works. The book “Iranian Culture in Bahram Beyzaie’s Cinema and Theatre: Paradigms of Being and Belonging” (Bloomsbury, 2023) by Saeed Talajooy is one such work that likely could not have been as comprehensive without Beyzai’s accessible presence and possibly interviews in exile. His ideas, like the concept of “epistemic privilege of the marginalized” which Talajooy elaborates, now circulate in English academic discourse, influencing comparative studies in world theater and film.

Despite being away, Beyzai remains deeply connected to Iran’s culture. Through the internet and global communications, his voice still reaches Iranians. He occasionally pens pieces that circulate in Persian literary circles or gives video messages in support of cultural causes. While he is physically absent, his cultural influence within Iran persists; young filmmakers still study his films (a restored Downpour finally screened in Tehran’s art circles after the restoration, to great interest), and theater students read his plays and theory.

However, there is an undeniable poignancy to Beyzai’s exile. Many Iranian observers lament that a genius of his stature had to leave to find peace to work. Some have referred to the “brain drain” and “cultural drain” that his departure symbolizes. Beyzai himself has been careful in public statements, but one can sense in his interviews a wistfulness for Iran. Nonetheless, he has channeled that longing productively: his works in exile often thematically involve exile or searching for home (the Stranger in the fog can be seen as any exile’s story; Bashu becomes even more symbolic as it is about finding refuge).

At Stanford, Beyzai also found the freedom to speak more openly about the philosophical underpinnings of his art. He could cite Nietzsche or Jung in lectures without fear of misinterpretation by censors. Indeed, he has mentioned, for instance, that the idea of eternal recurrence and cyclical time (a Nietzschean concept) resonates with how Iranian myths view history as repeating patterns – something he explores in plays where ancient events mirror modern ones. He has also alluded to Jung’s archetypes when discussing mythological characters, noting how figures like Rostam or Zahhāk embody collective fears and hopes, akin to archetypal roles. By engaging with these global thinkers, Beyzai in exile has effectively positioned Iranian cultural narratives within a broader human context, showing their relevance to universal questions of existence and memory.

Global recognition for Beyzai in the 2010s and 2020s also came in the form of awards and tributes, such as:

The Bita Prize for Persian Arts (2014) at Stanford which he received, praising both his aesthetic achievements and his “defense of artists’ rights to create freely” – a nod to his struggles against censorship.

Various film and theater festivals in Europe and North America have honored him, from retrospectives to lifetime achievement awards.

In scholarly arenas, he’s been compared to legendary filmmakers like Tarkovsky (for his spiritual cinematic language) and to playwrights like Brecht (for his critical approach to theater) in numerous analyses and panel discussions, effectively confirming that Beyzai belongs in the pantheon of world auteurs.

One might ask: has Beyzai continued making films in exile? Interestingly, he has not directed another feature film since Killing Mad Dogs (2001). It appears he channeled his creative energies more into theater productions and teaching after leaving Iran. There were mentions that he might adapt one of his scripts into a film abroad (some rumors of an English-language project or a film about Rumi, etc.), but funding and logistical issues (and perhaps his own preference for working in Persian) have so far prevented a new film. Nonetheless, he remains active as a writer; he has published some new plays and memoir-like writings in exile.

Crucially, Beyzai’s global legacy is not just in the content of his work, but in the example he sets as an artist. He is often cited as a paragon of integrity: a man who never compromised his vision despite pressures. He stands as a model for younger Iranian artists that it is possible to stay true to oneself and one’s culture, even if it requires sacrifice. His being in exile also means he now belongs to a lineage of great artists who did significant work outside their homeland (comparable in some ways to figures like Tagore, who engaged internationally, or Brecht, who wrote in exile). This diaspora dimension adds an interesting layer to his impact – he has become a cultural ambassador of Iran, presenting Persian art to Western audiences through both scholarly and artistic channels.

The “global Beyzai” is thus multifaceted: a teacher inspiring students of all backgrounds, a diaspora director keeping Persian theater alive abroad, a thinker engaging with global philosophy, and an Iranian luminary whose absence at home is itself a commentary on political conditions. In a poetic sense, one could say Beyzai’s own life became akin to one of his stories – the wise traveler forced away from his village, carrying with him the fire of his culture to light new lamps elsewhere.

Parallel to his achievements in theater and cinema, Bahram Beyzai has been an incredibly prolific writer. His literary works encompass a wide range: from screenplays and stage plays (many of which we’ve touched on) to essays, research monographs, and even fiction and poetry on occasion. Over the course of 50+ years, he has published more than 70 books, including plays, screenplays, scholarly works, and translations. This staggering output underscores Beyzai’s dedication to writing as the foundation of his art – he is as much a man of letters as a man of the stage or camera.

Some key categories of his literary contributions include:

Screenplays (Film Scripts): Beyzai has written far more screenplays than he was able to direct. For each of his 10 directed films, he has at least as many scripts that were never realized on film. These unfilmed screenplays were often published as literature. For instance, Sag o Zemestān (“The Dog and Winter”) and Kalagh (the screenplay which differs from the play) were published in collections. An important one was “The Tale of the Shroud-Wearing Commander” (Qesseh-ye Mir-e Kafanpush) written in 1979 – a script set perhaps in historical or allegorical context – published in 1984 but never filmed. Similarly, “Truths about Leila, the Daughter of Idris” as mentioned was published in 1982 after the film was halted. By publishing these scripts, Beyzai turned them into a form of literary art that could be read and analyzed even without being visualized. It’s a testament to their quality that many read like novellas or dramatic literature, offering rich dialogue and stage directions that paint the scene in readers’ minds. One might say these unfilmed scripts became part of modern Persian literary canon in their own right. The content of many of these reflects Beyzai’s persistent themes: Parde-ye Khane (The House’s Curtain) deals with domestic life and memory; Salto (Somersault) addresses political paranoia in an abstract way; others venture into historical fantasy territory. Scholars have catalogued at least a dozen screenplays by Beyzai that remain unfilmed, indicating how many potential films Iranian cinema lost to censorship.

Stage Plays (Published Texts): Beyond his performed plays, Beyzai wrote numerous others that were published but either never staged or staged much later. For example, “The Eastern Tale of Ferdowsi’s Daughter” (Prelude to Shahnameh) was written around the 1990s, exploring the Shahnameh legend of Ferdowsi and his daughter – this was eventually published as New Preface to the Shahnameh. He also wrote plays inspired by world literature, like an adaptation of King Lear’s themes set in Iran, or Māreh Marū (The Evil Serpent) reflecting Middle Eastern folklore. Many of his plays that couldn’t be produced in the strict post-revolution climate ended up being published in the 1990s and 2000s. These include Panbeh-Zan-e Harāsu (The Fear-Striking Cotton Beater) and Hasan’s Evening (a modern naqqāli story). Publishing them ensured that his creative ideas reached audiences, albeit in print.

Essays and Theory: We covered a lot about his theoretical writings, like Theatre in Iran, Where is Hezar Afsan?, and Seeking the Roots…. Additionally, he wrote essays on cinema: for instance, a piece reflecting on the role of women in Iranian cinema in which he delineated how female characters can be empowered – paralleling his Offscreen interview content. He also wrote on storytelling technique and dramatic literature. His essay “Namayesh-e Āyinī” (Ritual Drama) is considered a key piece that links Iranian religious rituals to drama form. Another interesting work is his foreword or critical commentary in the publication of certain classical texts; he wrote a new introduction to the Shahnameh itself (prefacing a modern edition), illustrating how he brings a dramatist’s perspective to Iran’s literary monuments. This introduction, titled New Preface to Shahnameh (1987), is effectively a dramatic script in which Ferdowsi’s daughter speaks out, symbolically rejecting the unjust reward offered to her father, giving voice to a voiceless figure in the classic – a very Beyzaiesque move.

Books and Monographs: Besides Theatre in Iran, Beyzai compiled anthologies of Iranian plays, wrote a treatise on Persian painting’s relation to theater, and assembled research on ta’ziyeh (one of his works detailed various ta’ziyeh performances historically). He even ventured into writing for children early on, with a story or two in the 1960s magazines aimed at youth. In the Stanford website’s list of Beyzai’s publications, one finds over 70 entries – which for any writer is exceptional, and for a practicing filmmaker even more so.

Unpublished or Incomplete Writings: There are hints that Beyzai has many drafts or planned projects that haven’t seen the light of day. For example, a novel he might have started (some Iranian authors often attempt novels; not sure if he did, but plausible). Also, diaries or memoirs: to date, Beyzai has not published an autobiography or memoir, but given his eloquence, one imagines he may have journals. If ever released, those could be precious historical documents. Some letters of his, correspondences (for instance with other literati like Ahmad Shamlou or Hooshang Golshiri), might exist but remain private.

The interplay of his literary and cinematic sides can be seen in how often his literary output provided blueprints for his films or plays. Practically every film he directed was based on his own script or play, meaning he conceived them first in writing. This underscores a creative equation he follows: that the written word (be it dialogue or scenario) is the backbone of visual storytelling. It aligns with classical Iranian artistic tradition where the poet and the reciter are central – Beyzai is in many ways a modern naqqāl (storyteller) whose medium can be paper, stage, or celluloid.

Critically, Beyzai’s writings have been analyzed by scholars as much as his films. His plays and screenplays are taught in Persian literature and drama courses. Some have been translated: Death of Yazdgerd has an English translation available, The Marionettes (another play) was translated, Arash and others as well, broadening his literary reach beyond Persian speakers. His essay “The Symbolism of Hezar Afsan” was partially translated in journals, etc.

An interesting aspect is the poetic quality of his writing. Many critics note that reading a Beyzai play is itself a poetic experience. He often uses rhythm, metaphor, and wordplay in Persian that’s hard to translate. For example, in Marg-e Yazdgerd, the Miller’s Wife has monologues that flow like epic poetry, full of rich imagery and allusion. Beyzai, being from a poet’s family and steeped in Persian literature, naturally writes Persian with a literary flair. He occasionally writes actual poems too – e.g., within his plays a character might recite verses he penned.

One cannot overlook his role in language preservation and innovation: Beyzai’s works, especially his theoretical books and plays, have enriched modern Persian vocabulary by reintroducing archaic terms or coining new phrases for theatrical concepts. For instance, in discussing drama he sometimes had to create Persian terminology for technical terms where none existed, given the previously underdeveloped Persian theater criticism lexicon.

In summary, Beyzai’s literary works form the bedrock of his artistic legacy. They serve multiple purposes

Documenting and expanding Iran’s cultural narratives (his research works).

Providing content for performance (his plays and screenplays).

Standing as literary art on their own (many read his published scripts like literature).

Contributing to Persian intellectual discourse (his essays on art, culture, identity).

Even if one day none of his films survived (hypothetically), his books and writings would continue to testify to the breadth of his intellect and creativity. As a scholar said, “His prolific output comprises seventy-seven plays, fourteen feature films, and countless essays”, which is a legacy not just for one career but for an entire culture’s archive.

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that Beyzai continues to write. In recent years, he’s reportedly working on a new screenplay and finishing a multi-volume study on Iranian theater history’s lesser-known aspects. As he approaches his late 80s, his pen remains active, embodying the Persian adage, “tha pen is the tongue of the soul,” and Beyzai’s soul has indeed spoken volumes.

Throughout Beyzai’s multifaceted oeuvre, a constellation of critical themes recurs, lending his work a remarkable coherence despite its diversity of forms. These themes – identity, time, history, politics, memory, gender, and symbolism, among others – are interwoven with philosophical and artistic frameworks that reflect both Iranian intellectual traditions and global ideas.

Identity and Belonging; One overarching concern in Beyzai’s work is the question of identity – personal, cultural, and national. His characters often grapple with understanding themselves in the face of societal roles or historical narratives imposed on them. For instance, in his plays like So Dies Pahlavan Akbar, the protagonist’s sense of self is at odds with the legend he’s become to others; and in Truths about Leila, the heroine must carve out a new identity in a world that labels her unjustly. Beyzai is fascinated by how identity is constructed and perceived – “how a person’s understanding of their life may be different from what others assume about that person”. This theme ties to philosopher Carl Jung’s concept of individuation and the masks (persona) we wear. In fact, Beyzai wrote a comparative piece about “Mask and Face” drawing parallels between his work and Luigi Pirandello’s, exploring how characters wear societal masks. On a national scale, Beyzai’s return to myths and historical figures is part of an exploration of Iranian cultural identity. He offers “alternative narratives” that question official historiography and celebrate marginalized voices. As Dr. Talajooy notes, Beyzai “depicts the hidden realities of people’s lives in the past and present” and deconstructs grandiose official identities. The concept of identity in Beyzai is often fluid and self-determined – a Nietzschean idea, perhaps, in the sense of forging one’s own values and self beyond societal dictates.

Time and Memory;

Beyzai’s storytelling frequently plays with time – not just chronological time, but mythic time and cyclical time. In The Stranger and the Fog, time is obscured by the fog; in Death of Yazdgerd, time almost stands still as one event is re-examined repeatedly from different angles; in The Travelers, the past and present collide through memory and photography. Beyzai often invokes the concept of a circular or suspended time, akin to Mircea Eliade’s notion of sacred time in myths (where time is eternal and events recur). The article in Theater Journal on “Manifestation of Mythical Time in Beyzai’s Works” found that he succeeds in making time “mythical” by subjectifying it and focusing on events rather than linear progression. There’s also a sense of history repeating or rhyming – e.g., plays set in Mongol era reflecting modern conditions. This aligns loosely with Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence – the idea that events recur and must be confronted anew – which can be felt in Beyzai’s many revisitations of similar conflicts across eras. Memory, in his work, is both personal and collective. Characters haunted by memory (Naii in Bashu constantly remembers her missing husband; the villagers in Stranger and Fog gradually recall the truth) symbolize a society grappling with its collective memory and forgetting. Beyzai shows that forgetting has consequences – a line from Stranger and Fog review: “forgetting, like remembering, has consequences…the fog is history, guilt, the past that never fully dissipates”. This philosophical stance resonates with Jung’s collective unconscious – the idea that past traumas and tales live on in the psyche until acknowledged.

History and Politics; While Beyzai’s works are rarely overtly propagandistic, they are intensely political in implication. By delving into history, he implicitly comments on present politics. For example, Death of Yazdgerd (about the fall of a despotic regime) debuted in 1980, clearly reflecting on current revolutions and what comes after. Beyzai’s approach to political critique is subtle, layered in allegory – reminiscent of Bertolt Brecht’s principle of encouraging critical distance. Like Brecht, Beyzai doesn’t spoon-feed a message; he sets up a scenario where power dynamics are laid bare (like the trial in Yazdgerd, or the corrupt patriarchs in Killing Mad Dogs) and lets the audience draw conclusions. A specific theme is the sacrifice of intellectuals and creatives in oppressive systems – his heroes are often writers, teachers, or artists pitted against violence and dogma. This is part of what Talajooy calls Beyzai’s “sacrificial tragic paradigm” where creative individuals become martyrs confronting tyranny. It has echoes of Camus’ rebel-hero as well as the Iranian concept of the poet as societal conscience. Politically, Beyzai stands for humanism against fanaticism – a stance that put him at odds with various regimes.

Gender and Feminine Power; Perhaps one of the most celebrated aspects of Beyzai’s work is his treatment of women and gender roles. He is often cited as a feminist voice in Iranian art. His female characters are complex, resilient, and often central to resolving the narrative conflicts. They “transcend their boundaries through innate power”. For instance, Naii in Bashu is the moral backbone who defies societal expectations to protect a child; Golrokh in Killing Mad Dogs braves a hostile patriarchy with intellect and will. Beyzai’s women are not idealized angels or one-dimensional victims; they have agency, desires, and flaws. This ties to Persian mythic influences too – he noticed, as one source notes, that in folktales women’s roles are bolder and often savior-like, and he amplified that. Thematically, he often portrays the clash between feminine wisdom/compassion and masculine aggression/ignorance, ultimately showing that society’s redemption often lies in embracing traditionally “feminine” virtues like empathy, creativity, and nurturing. The correlation with Jungian archetypes is strong here: many of his stories seem to center on the need to integrate the Anima (feminine) into the conscious psyche of a culture overly dominated by Animus (masculine) energy. Also, one could see influences of Simone de Beauvoir’s notion that women are not “the second sex” but equals; Beyzai’s persistent championing of female intellect (Isalat’s wife Asiyeh, a teacher of the deaf in The Crow, is more insightful than her husband) underlines that.

Symbolism and Metaphysics; Beyzai’s art is richly symbolic. Nearly every object or color in his films/plays can carry meaning. Mirrors represent self-reflection or truth; fog symbolizes uncertainty or historical amnesia; fire could symbolize purification or destruction; water often represents life and change. He uses symbols in a way that sometimes aligns with Persian mystic tradition (for example, the “chalice” symbol that appears in his writing about Jamshid – a reference to Jamshid’s cup of divination, which he discusses symbolizing the illuminated heart). This direct reference to mystic symbolism shows how he weaves metaphysical ideas into his narratives. There’s a Sufi influence at times: the journey of self-discovery (like Bashu’s journey or the Stranger’s plight) echoes the Sufi path of the seeker, and the presence of guiding female figures or wise fools resonates with Sufi tales (like Rumi’s stories where wisdom comes from unexpected sources). Beyzai, while secular, taps into that spiritual symbolism to add depth. For example, in Bashu, some critics interpret Naii’s character as mother-earth or a divine maternal archetype guiding Bashu (her name “Naii” even evokes “Nai” meaning reed flute, an instrument central to Rumi’s poetry as the voice of the divine longing).