Listen to the reed, how it tells a tale, complaining of separations– so begins Rumi’s Masnavi, and so, in spirit, begins the cinema of Ali Hatami. In the flicker of film frames and the hush of an old Iranian tea house, Hatami’s work sings of separation: the distance between a modern nation and its cultural soul, between the Iran that is and the Iran that was. His films play like poetic elegies and celebrations at once, each a naghali (traditional storytelling) session on celluloid, each a verse in the epic of a people. The Tehran Times aptly dubbed Hatami “the Hafez of Iranian cinema” for the native lyricism and poetic ambiance of his movies . Indeed, like the verses of Hafez or Sa’di, Hatami’s films are at once deeply cultural and timelessly human – lush tapestries of Persian adab (culture, literature) reimagined on the screen. Watching them, one seems to wander into a Persian miniature painting come alive, guided by a storyteller’s voice, by turns tender, philosophical, and barbed with satire. Hatami’s cinema was a mirror of Iran, and in its reflection glimmers the myriad faces of Persian literature, folklore, and philosophy, rediscovered through the camera’s eye.

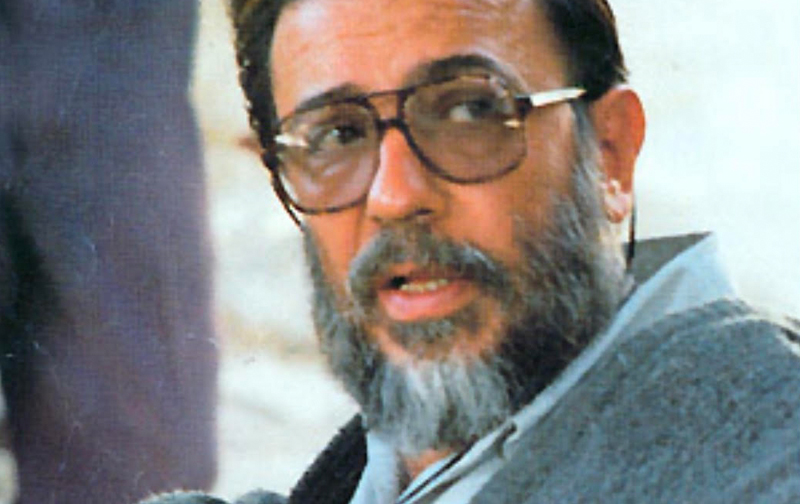

To speak of Ali Hatami is to invoke the image of a man as much a poet as a filmmaker – a slender figure with a discerning gaze, a modern khonyaagar (minstrel) armed with a director’s lens instead of a lute. Born in 1944 in the heart of Tehran’s old district (the winding Shapur Street, in Ordibehesht Alley) , Hatami grew up amidst the living echoes of history. As a child he roamed the very alleys that decades later he would painstakingly recreate in his masterwork Hezardastan. His father was a printer, surrounded by trays of Persian letters; young Ali literally grew up with letters, steeped in the written word and lore of his land . In an old family house, he first beheld the magic of an 8mm projector throwing flickering images on a wall – an experience he later likened to “discovering the magic of cinema with the cinema itself.” One can imagine the boy’s eyes widening in that projector’s glow, as if a genie from the lamp of technology revealed to him new realms of storytelling. From that moment, the path of his life found its guiding light. Hatami would carry within him both the text and the image: the rich literary heritage of Iran and the visual dreamscape of film. Like a character out of a Bildungsroman, he set out to unite these two worlds – to make cinema speak in the ornate, soulful cadences of Persian art and myth.

Hatami’s formal training at the College of Dramatic Arts gave him the tools of theater and narrative, but it was his informal training – the lullabies of his mother, the sermons and ta’ziyeh (passion plays) of the streets, the coffeehouse storytellers reciting Shahnameh – that truly shaped his artistic voice. His earliest creative works were stage plays and teleplays, and tellingly their subjects were drawn from folklore and classical tales. He wrote pieces like “The Demon and Bald Hassan” and “City of Oranges” in the 1960s , already signaling his penchant for blending mythic imagination with quotidian humor. In 1970, at only 26, he made his directorial film debut with Hasan Kachal (Hasan the Bald), which is celebrated as the first Iranian musical film . Hasan Kachal is a whimsical retelling of a Persian folktale – the story of a simple bald village boy who outsmarts an ogre through wit. Hatami transformed this beloved folktale into a vibrant cinematic fantasy, complete with song-and-dance and richly colored sets evoking Persian miniature paintings. It was a bold experiment: no one had seen an Iranian musical before, yet Hatami’s faith in the indigenous story paid off. The film was warmly received , enchanting audiences with its melodious dialogues and traditional Iranian ambiance of fairy-tale architecture and costumes . In Hasan Kachal, the young director essentially declared his mission – to marry Iran’s ancient tales to the modern medium of film, to prove that Persian folklore could sing and dance on the silver screen and still move contemporary hearts. Just as Ferdowsi in the 10th century had proclaimed, (“For thirty years I suffered much pain; I have revived Persia with my Persian [verse]”), Hatami in the 1970s took it upon himself to revive Persian culture in the language of cinema. His films would be his Shahnameh, a chronicle of the Iranian soul, painstakingly brought to life through dialogue, design, and dream.

Throughout the 1970s, Hatami honed this distinctive style in a string of films that each celebrated a facet of Iranian culture or history. In Toghi (The Pigeon) (1970) and Baba Shamal (1971), he crafted melodramas spiced with old Tehran folklore – stories of love and honor among the urban poor, imbued with the idioms and music of the Iranian street. Baba Shamal in particular was a kind of modern kojasteh (ballad) about a rowdy minstrel, staged almost like a musical comedy of Tehran’s alleyways . Then came 1972, an annus mirabilis in which the prolific Hatami released Qalandar, Sattar Khan, and Khastegar (The Suitor) one after another . Each of these films further defined his personal folklore. Sattar Khan (1972) was especially significant: a historical biopic about one of the heroes of Iran’s Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911). Rather than a dry patriotic retelling, Hatami approached Sattar Khan’s legend from an unexpected angle – humanizing the icon, showing the uprising from another perspective and focusing on the unsung companions like Baqer Khan . Critics praised Sattar Khan for its original take on history , as Hatami infused the drama with intimate, everyday moments that made these national heroes relatable. It was history reimagined as lived experience, much as a storyteller might add personal flourishes to a well-known tale by Ferdowsi to captivate an audience anew. Meanwhile The Suitor was a comedic social commentary on traditional marriage customs, again interweaving sharp satire with affection for the quirks of Iranian life. By the mid-1970s, Hatami had proven himself a master at navigating between the past and present, between reverence and critique. His films felt like old wine in a new flask – the vintage flavors of Persian anecdote, proverb, and song poured into the youthful form of cinema.

It was inevitable that such a keen student of culture would turn to the ultimate Iranian art: poetry and mysticism. In 1973, Hatami created a television series called Dastan-haye Molana (Rumi’s Tales), dramatizing fables from Rumi’s Masnavi for the small screen . One can imagine Iranian families in the ’70s gathering around their TV as they once did around the carpet, listening to a morshed (sage) recount Sufi parables – except now the morshed was Hatami, orchestrating actors and images to convey Rumi’s wisdom. Two years later, he directed Soltan-e Sahebgharan (1975), an ambitious historical TV epic about the Qajar king Naser al-Din Shah and his Premier, Amir Kabir. Soltan-e Sahebgharan (literally “The King of the Owners of Time”) depicted the turbulent court politics of the 19th century and the eventual assassination of the Shah. Here Hatami first flexed the muscles of historical allegory that he would later perfect: using a bygone era to comment obliquely on themes of power, justice, and change that resonated with contemporary Iran. By the time the 1970s drew to a close, Hatami had acquired a reputation as Iran’s premier cinematic storyteller, a national treasure weaving the nation’s memory on film. Many critics consider Sooteh-Delan (Burnt Hearts, 1977) – his last pre-revolution feature – to be Hatami’s preeminent masterpiece of that era . A haunting love story set in the old neighborhoods of Tehran, Sooteh-Delan follows a cast of lonely, aching characters (a terminally ill young man, his devoted brother, a beautiful cabaret dancer) whose fates entwine in a house filled with both joy and sorrow. The film’s title means “Broken-hearted Ones” or literally “Burnt Hearts,” evoking the Sufi concept of hearts singed by the flame of love. Critics lauded Sooteh-Delan for its complete harmony between form and content, praising how Hatami’s poetic dialogue and nostalgic set designs perfectly complemented the bittersweet narrative . Watching Sooteh-Delan is like stepping into a delicate ghazal by Hafez: it visualizes the clash of love and fate in a richly textured, metaphorical Tehran – a city of shomal winds and gharibeh strangers, of old Qajar-era houses decaying under neon lights, where a classical tar (lute) melody might drift in from a nearby courtyard to underscore a lover’s despair. Hatami had achieved a cinema in which story, setting, and soul were fused, creating what one reviewer called “the most complete film of Hatami before the revolution” . In it, one senses the influences of Persian mystic poets – the notion that beauty and pain are intertwined, that (“Whoever lives not in love is not truly alive… and he who lives with heart aflame in love shall never die”). Hatami does not quote this famous Hafez line directly in the film, yet the sentiment permeates Sooteh-Delan: love outlasts death, and the artist’s act of loving his culture grants him immortality in the hearts of his people.

Then, in 1979, history itself intervened in Hatami’s story: the Islamic Revolution swept across Iran, toppling the monarchy and ushering in a new sociopolitical era. Many artists struggled to find their footing amidst the cultural upheaval that followed. But Ali Hatami faced this turning point with characteristic resolve and creativity. It was as if the currents of historical change only emboldened him to dive deeper into history’s ocean for inspiration. In the very year of the Revolution, Hatami embarked on what would become his magnum opus – a project so ambitious and consuming that it took nearly a decade to complete and remains legendary in Iranian cinema. This was Hezardastan – literally meaning “Thousand-hands” and also an epithet for the nightingale in Persian (the bird of a thousand tales). Hezardastan was conceived as an epic television series, a sweeping chronicle of Iranian life during the early 20th century, specifically the twilight of the Qajar dynasty and the upheavals of the 1920s–40s. Hatami initially titled it “Silk Road,” suggesting a grand journey through the tapestry of Iran’s past . In undertaking Hezardastan, Hatami was consciously creating his Shahnameh on screen – a “Book of Kings” not of mythic ancient Persia, but of the more recent, living memory of Tehran and its people in a time of tumult.

The production of Hezardastan was itself the stuff of myth. Hatami poured his heart, soul, and years of his life into it. He reportedly decamped to the countryside in France for a time simply to concentrate on writing the massive script, free from distractions . Ever the perfectionist, he revised and refined the screenplay relentlessly – it is said he rewrote the script over ten times until it met his standards . This labor bore fruit in an intricately layered narrative that reflects the density of a great Persian novel. Hezardastan ultimately aired from 1987, after an arduous 8-year production spanning 1979 to 1987 . It comprises two parts: the first set in the last days of the Qajar era (circa late 1910s) and the second part during World War II and the Allied occupation of Iran in 1941 . Spanning these turbulent decades, the series explores the social and political undercurrents that shaped modern Iran – from the waning of the old aristocracy to the rise of new forces (nationalists, opportunists, foreign meddlers) under the nascent Pahlavi regime. Yet Hezardastan is far from a dry history lesson; it is structured like a grand mystery-thriller, with personal dramas and conspiracies that gradually reveal a larger picture of corruption and national soul-searching. The central thread follows Reza Khoshnevis, also known as Reza “Tofangchi” (Reza the Rifleman) . Reza is a humble man from Isfahan who, in his youth, takes up a gun and becomes involved in a campaign of assassinations during the chaotic years of Ahmad Shah (the last Qajar king) . As we learn, Reza’s initial zeal for justice through the gun leads only to disillusionment. In the latter part of his life – now older and full of regret – he renounces violence and turns to the peaceful art of calligraphy, becoming “Reza Khoshnevis” (Reza the Scribe) . This transformation of the protagonist from tofangchi to khoshnevis is one of the most poignant allegories Hatami ever crafted: it symbolizes Iran’s own search for identity between the gun and the pen, between revolutionary fervor and cultural continuity. It is as if Hatami is saying that the true salvation of the nation lies not in bloodshed but in preserving its art, its “penmanship” of civilization.

Woven through Reza’s personal journey is a web of other characters and plots, centered around a mysterious, shadowy figure known as Hezar Dastan (the “Thousand Hands”). Played by the legendary actor Ezzatollah Entezami, Khan Hezar Dastan is an aging strongman, a once-powerful lord with his fingers in every pie – a Don Corleone-like kingpin whose nickname “Thousand Hands” suggests his invisible grip on Tehran’s affairs. He is at once a flesh-and-blood character (a man named Khan-e Mozafar) and a symbolic embodiment of the old system of tyranny and intrigue that never truly dies. The fictional town in the series bears the same name, Hezardastan, blurring the line between the man and the environment – as if corruption itself casts a thousand-handed shadow over the city. Through masterful storytelling, Hatami shows how ordinary people like Reza become pawns in the games of such larger powers, and how the ripples of global events (like World War II and the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran) disrupt the lives of tailors, bookbinders, train conductors, and schoolteachers. By mixing real history with fictional characters , Hatami achieves a tapestry that is both epic and intimate. In one scene, we are in the dilapidated elegance of a Qajar palace as conspirators whisper; in the next, we are in the smoke-filled warmth of a ghahvekhaneh (coffeehouse) where a storyteller recites verses of Ferdowsi to a spellbound crowd, even as a hitman lurks in the corner with a pistol. Such juxtapositions make Hezardastan a meditation on history itself – is history the tale told by the victor (the conspirators), or by the poet (the coffeehouse bard), or by the common man who suffers its slings and arrows? Hatami’s answer seems to be that history lives in our stories and memories; it is kept alive by the act of storytelling, whether that of Ferdowsi writing the Shahnameh under patronage or Hatami filming Hezardastan under revolution.

The making of Hezardastan became an epic legend in its own right. Determined to authentically portray 1920s Tehran, Hatami undertook the construction of an entire historical town as the series’ set. On a barren stretch outside Tehran, he built what came to be known as the Ghazali Cinema City – a sprawling backlot recreating the streets, cafes, and architecture of old Tehran with obsessive detail . This included period-accurate shops, a grand hotel, a newspaper office, a courthouse – a whole world in which his story could unfold naturally. It was essentially Iran’s first true movie studio backlot , a Persian answer to Hollywood’s set towns, yet imbued with the soulfulness of an Iranian alley. Hatami’s crew even crafted small details like vintage posters, phonograph records, matchboxes and streetcar tracks, to ensure that every frame breathed authenticity. Years later, his wife Zari Khoshkam reminisced that the arduous effort of building this cinematic town consumed their family life – Hatami often joked (not without sadness) that in those years he was so busy “I did not see my daughter Leila grow up” . One imagines him on set, a man possessed by vision, wearing the hats of director, art director, even shovel-in-hand laborer at times to get the sets just right . Zari described how he would personally carry bricks, supervise carpenters, even lay pavement if needed . Such was Hatami’s devotion: he gave Hezardastan ten years of his life and the fire of his youth . “For the Hezardastan series, I put my youth into it,” he said simply, and it is no exaggeration . This sacrifice echoes the devotion of Persian masters past – one is reminded of the 12th-century Sufi Farid ud-Din Attar, who counseled (“Step onto the path and ask no questions; the road itself will reveal how to proceed”). Hatami stepped onto the path of this colossal project not knowing fully how it would reach completion, but trusting in the journey. Through wars, budget crises, and political scrutiny, he kept going, as if guided by an inner certainty that this tale needed to be told.

When Hezardastan finally aired on national television in 1987, it was an immediate cultural event. Audiences across Iran sat riveted each week, drawn in by the saga’s suspense and its ravishing period atmosphere. Many older viewers were moved to nostalgia or tears – here on screen was the Tehran of their youth or of their parents’ stories, reborn. Younger viewers, for whom those days were mere textbook lines, suddenly could see, hear, and feel their history in a visceral way. The series featured a constellation of Iran’s finest actors: Ezzatollah Entezami, Ali Nassirian, Mohammad-Ali Keshavarz, Jamshid Mashayekhi – a dream cast whose powerful performances gave the story gravitas . Critics hailed Hezardastan as a triumph; decades later, it was voted the best Iranian TV series ever made . But beyond acclaim, Hezardastan entered the Iranian psyche. Its dialogues and characters became part of popular memory, quoted in conversations, referenced as moral parables. For example, the figure of “Moffatesh-e Shesh Angoshti” (the Six-Fingered Inspector, a detective character in the series) became a byword for relentless (if sometimes comical) investigation; the villainous charisma of Hezar Dastan himself became shorthand for the idea of hidden power behind the scenes. Even the show’s haunting theme music – a sorrowful orchestral piece that fused Persian traditional modes with Western instrumentation – evoked an instant mood of historical reflection whenever played. Hezardastan had succeeded in Hatami’s deepest aim: to rekindle historical memory as a living, emotional experience. Just as a nightingale (hezar-dastan) sings countless songs at dusk, Hatami’s Hezardastan sang myriad truths about identity, tyranny, sacrifice, and fate – ensuring that the stories of Iran’s past would not be forgotten in the din of the present.

Philosophically, Hezardastan encapsulates Hatami’s worldview on historical memory, identity, language, and nationhood. The series suggests that history is not a distant chronicle but a continuous conversation between past and present. In one of its most moving moments, Reza the Scribe (the older Reza) calmly writes out verses of Sa’di or Rumi in elegant calligraphy while outside his shop the world is in turmoil. The camera lingers on the shapes of Persian letters as his pen glides – a quiet act of preservation amid chaos. This image is emblematic of Hatami’s credo: that the Persian zabaan (language) and farhang (culture) are what root a people through tumultuous times. Reza’s calligraphy is a metaphor for Hatami’s own films – each stroke a gesture of remembrance. There is a sense in the series (and indeed across Hatami’s oeuvre) that the Persian language carries the soul of the nation, and to cherish its poetry and idiom is an act of patriotic devotion as vital as any political deed. Hatami often had his characters speak in a slightly archaic Persian, peppered with idioms, proverbs, and a charming Tehrani accent of the old days. Dialogues in Hezardastan and other films sometimes sound like poems put into everyday speech, giving even simple exchanges a rhythmic, proverbial weight. This was part of Hatami’s signature – his melodious, unorthodox dialogue writing , which celebrated the musicality of Persian. Little wonder the press anointed him the Hafez of cinema: as Hafez’s ghazals are memorized and recited by Iranians as quotidian philosophy, so do Hatami’s cinematic lines live on in common parlance. For example, in Hatami’s wartime romance Khastegar a father quips to a would-be suitor, (“First find yourself, then find my daughter!”), a line which became a witty proverb on knowing one’s identity before seeking partnership. Through such flourishes, Hatami challenged and charmed his audience into reflecting on identity. He believed, like Ferdowsi before him, that the past is prologue –(“the past is the lamp lighting the future”), as a Persian saying goes. Each of his films asks implicitly: Who are we, if we forget who we were? And conversely, What of the past do we carry into the future?

This concern with identity extended to Hatami’s exploration of nationhood and modernity. Coming of age as a filmmaker during the rapid modernization of the Pahlavi era and then the revolutionary fervor of the Islamic Republic, Hatami saw Iran pendulum between Westernization and nativism, between forgetting and mythologizing its past. His films often critique blind Western imitation while also warning against severing ties with global progress. A brilliant example is Jafar Khan az Farang Bargashte (“Jafar Khan Has Returned from Abroad”, 1984), which Hatami adapted from a 1920s satirical play by Hassan Moghadam . The story centers on Jafar Khan, a Persian man who returns from Europe thoroughly “farangified” – aping European manners ridiculously and despising his own traditions. Hatami’s film treats the subject with comedic exuberance, dressing Jafar in mis-fitting Western suits and having him spout malapropisms of English and French, all to lampoon the superficial westernization among some Iranians of the early 20th century (and by implication, the 1980s). Yet beneath the farce lies a gentle plea for cultural balance: to appreciate one’s heritage even as one learns from the world. In one scene, an exasperated elder recites Sa’di’s famous lines to Jafar: (“Human beings are limbs of one body, created of one essence”) – reminding him that one cannot cut off a limb (one’s own culture) without pain. Hatami integrated such literary citations seamlessly, as natural parts of his characters’ speech or as subtle allusions. The effect is to elevate a comedic social critique into a dialogue with classical Persian wisdom on chosun kardan (self-knowledge) and ghorbat (cultural estrangement).

After the monumental achievement of Hezardastan, Hatami continued to make films that mined history and literature in surprising ways. In 1982 he directed Hajji Washington, a daring tragicomedy about Iran’s first ambassador to the United States in the late 19th century. The film is based on the true story of Haj Hossein-Gholi Noori, who was sent by the Qajar king to Washington D.C. in 1888 . In Hatami’s hands this historical footnote becomes a bittersweet satire of cultural clash and bureaucratic absurdity. Isolated and underfunded, Hajji Washington (played by the great actor Ezzatollah Entezami) finds himself in a foreign land with no support – his embassy’s budget is so meager he has to fire the staff, and he ends up a lone dignitary trying to represent a nation that has all but forgotten him . Hatami milks the situation for Chaplin-esque humor (a Persian in a frock coat solemnly strolling by the Potomac, composing florid letters to a king who never reads them) and then gradually turns the comedy into pathos as the ambassador’s dignity crumbles. Hajji Washington was effectively a commentary on Iran’s early encounters with the West – the naivety, the miscommunications, the poignant sense of a small nation struggling for respect on the world stage. The Iranian authorities, perhaps sensing subtext critical of governance (or perhaps uncomfortable with a sympathetic portrayal of a Qajar era figure during fervently anti-monarchist post-revolution days), banned the film after a token screening at Fajr Festival . Hatami did not live to see Hajji Washington released to the public; it was only in 1998, two years after his death, that audiences finally saw it broadcast on TV . Despite this suppression, Hajji Washington has gained recognition as one of Hatami’s most profound works – a film that in a gentle, humanistic way asks how one remains Iranian abroad, and what loyalties mean in a world of realpolitik. The forlorn ambassador talking to his goldfish (named after Persian heroes to keep him company) in a grand empty embassy becomes an enduring metaphor for Iran’s simultaneous pride and isolation on the global stage.

In 1984, Hatami returned to the theme of art and authority with Kamalolmolk, a period drama about the life of the famed court painter Mohammad Ghaffari, known as Kamal-ol-Molk. This film spans the late Qajar and early Pahlavi periods, depicting Kamalolmolk’s relationship with kings – first the indulgent Naser al-Din Shah, then the reformist Reza Shah – and the challenges he faces in maintaining artistic integrity under patronage . Hatami, himself a sort of visual artist negotiating with the powers of his day, clearly identified with Kamalolmolk’s trials. In one memorable scene, the aging painter refuses to flatter Reza Shah with unrealistic portrayals; when ordered to paint the new modern military academy, he paints not only its grandeur but also the muddy boots and weary faces of the soldiers. The Shah is displeased, but Kamalolmolk stands by the truth of his art. Hatami tried to “preserve both the historical authenticity and a critique of cultural politics of the time” in this film . By focusing on the tension between an artist and his ruler, Hatami explores the timeless question: Does art serve power, or serve higher ideals? The film subtly critiques the cultural policy of every era – including perhaps his own – that tries to co-opt art for its agenda, by showing how Kamalolmolk navigates censorship and expectation. At one point Kamalolmolk recites (under his breath) a couplet from Attar:(“if you are a seeker, you must wade through blood”) – suggesting the sacrifices endured for truth. Kamalolmolk is lovingly crafted, with sumptuous cinematography mimicking the painter’s eye (each frame could be a tableau) and heartfelt performances, especially by actor Jamshid Mashayekhi in the title role. Iranian audiences, well acquainted with Kamalolmolk as a national icon of art, appreciated Hatami’s nuanced portrayal. The film stands as both a tribute to a great painter and a reflective self-portrait of Hatami as a conscientious artist grappling with historical forces.

As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, Hatami turned his attention to more intimate, contemporary subjects – but even these he filtered through the lens of tradition and allegory. In 1989 he directed Madar (Mother), a deeply moving domestic drama that, like its title, revolves around the figure of an aged mother and her grown children. The storyline is simple yet profound: a dying mother in a nursing home wishes to gather her estranged children together in their old family house for a few final days . The siblings – each busy with their own lives and grievances – return and confront old tensions, rediscovering their bonds only as their mother’s life ebbs away. Hatami infuses Mother with a nostalgic glow; the house itself becomes a character, full of memories of laughter and quarrels. In one scene, as the mother lies resting, the electricity suddenly goes out at night – the siblings scramble to light oil lamps, and in that warm flickering light they begin to share childhood stories, bridging years of distance. Mother resonated strongly with Iranian viewers, who saw in it not only their own family dynamics but a metaphor for their motherland. Some interpreted the mother as symbolic of Mother Iran, who in her twilight calls home all her wayward children (perhaps a subtle call for unity after the divisive revolution and war years). Whether or not one reads it politically, the film offers a universal message about remembering one’s roots. There is a line in the film, spoken by the gentle, wise eldest son to his bickering siblings: – “We are all of one soil.” This line, reminiscent of Sa’di’s Bani Adam verses of unity, encapsulates Hatami’s humanist philosophy. In Mother, as in Sa’di’s famous poem, if one member of the family/nation is in pain, others cannot remain untouched. Hatami’s camera lovingly lingers on details that evoke heritage – the mother’s hands kneading dough for the traditional bread, the samovar steaming as the siblings talk through the night, the lullaby she hums which is the same lullaby her grandchildren will carry on. Such touches gave the film a literary depth; it felt like a short story by Jalal Al-e Ahmad or even a chapter from Sa’di’s Golestan, using a specific scenario to illustrate a moral: cherish your loved ones before they depart, and in a broader sense, cherish the cultural hearth that warms you.

In 1992, Hatami made what would be his final completed feature, Delshodegan (The Love-Stricken). If Mother was about family memory, Delshodegan was about cultural memory – specifically the preservation of traditional Persian music. Set around the 1910s during the reign of Ahmad Shah Qajar , the film follows a group of master musicians who undertake a journey to Europe. Their mission, under the pretext of representing Persian art abroad, is actually to record and save the authentic repertoire of Iranian music, which they fear is fading amid the chaos of the times . This premise was inspired by real events (the early recordings of Persian classical music were indeed made in the 1900s in Paris and London). In the film, Hatami portrays the musicians – including a tar virtuoso, a vocalist, a kemancheh (spike fiddle) player – as passionate guardians of an ancient legacy. They speak of the radif (the canonical repertoire of Persian music) with reverence, as though it were a holy book, and they fret that as Western influences grow and old masters die, this intangible heritage could be lost. Delshodegan is suffused with music; its very title can mean “those struck by love” (enamored) but also hints at “love-struck melodies.” The film’s highlight is a scene where these musicians perform together one last time in Iran before departing – a transcendent concert in a candlelit hall, where the camera closes in on each artist’s face lost in the ecstasy (wajd) of the music. The leading singer’s voice (voiced by the acclaimed traditional singer Homayoun Shajarian in the soundtrack) soars in an aching rendition of a Rumi ghazal, bringing tears to the eyes of those present (and the audience). It is a moment that encapsulates Hatami’s belief in the spiritual power of art. Delshodegan suggests that in art lies the counter-memory to all that history tries to erase. Even as political events in the film threaten to disrupt their journey – war on the horizon, bureaucrats indifferent to art – the musicians persist, love-stricken by their craft. A scholar analyzing this film (Negar Mottahedeh) noted that Delshodegan serves as a “missive from Iran’s national music” – a kind of protest against forgetting . Indeed, Hatami dedicated the film to the masters of Persian music. Through it, he practically performs a cinematic tajalli (manifestation) of Attar’s line:– “Let not our music flee from the soul.” In one dialogue, a character says, “If we do not save these melodies, we will become strangers even to our own past.” That sentiment could well be Hatami’s own motto regarding all forms of cultural expression.

Delshodegan was very popular in Iran, not least because it reintroduced younger generations to the splendor of classical music in an entertaining narrative. It also completes an informal trilogy of Hatami’s post-revolution works that grapple with heritage: Hajji Washington (political heritage and dignity), Kamalolmolk (artistic heritage and integrity), Delshodegan (musical heritage and continuity). In each, one sees Hatami’s philosophical side contemplating the interplay of memory and identity. By the early 1990s, the Iranian cinema that once shunned him for being “too native” or not internationally fashionable had come around – the global success of other Iranian filmmakers who used poetic realism (like Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf) brought new attention to Hatami’s unique contributions. Critics noted that while Hatami’s films seldom traveled to foreign festivals, at home he had cultivated a cinema of cultural introspection. As one observer put it, Hatami’s movies “are concerned with Persian culture and create a memoir for the audience. He paints the people’s culture, etiquette, and values on the screen” . For this reason, some nicknamed him “the Sa’di of cinema” – because like Sa’di’s didactic yet beautiful prose that captured 13th-century Persian society, Hatami’s films captured 20th-century Iranian society with wisdom and grace.

In the mid-1990s, Hatami began an earnest research for a new film about the legendary Iranian Olympic wrestler Gholamreza Takhti – a figure of almost mythic stature symbolizing patriotism and virtue. It seemed fitting: Hatami’s entire career had been about heroizing the right people (folk heroes, artists, mothers) instead of the falsely glorified. Takhti, often called “the Champion of Champions” and a national hero mourned by millions upon his mysterious death, was a perfect subject for Hatami’s interest in the intersection of individual virtue and national identity. Unfortunately, fate intervened cruelly. Partway through making Takhti, Ali Hatami was diagnosed with cancer. Despite illness, he managed to film some scenes, but his health deteriorated rapidly. On December 7, 1996, at the age of 52, Hatami passed away, leaving Takhti unfinished . The film was later completed by director Behrouz Afkhami , but one can only wonder how Hatami himself would have sanctified Takhti’s story. The incomplete status of Takhti is metaphorically resonant: it is as if the storyteller of the nation was reciting a tale by the fire and left mid-sentence, leaving his listeners yearning for more.

When Ali Hatami died, Iran lost not just a filmmaker, but a guardian of its cultural memory. Yet, true to a line of Persian poetry he loved, – “It is not the nature of the lamp’s flame to die out” . Hatami’s light did not extinguish. His works continue to illuminate Iranian hearts and minds. In a deeply poetic twist, his daughter Leila Hatami has become a renowned actress who carries forward something of his spirit (she in fact debuted as a child in her father’s Hezardastan and later starred in the Oscar-winning A Separation). It is as if the cinematic lineage he began is now part of Iran’s living legacy.

To truly understand Hatami’s significance, it is enlightening to compare him with some global contemporaries and predecessors – towering figures who, like him, approached cinema as art and philosophy. There is a convergence of vision between Hatami and these masters that transcends borders, affirming that he indeed belongs in the pantheon of world auteurs. Consider Andrei Tarkovsky, the Russian poet of cinema. Tarkovsky’s films (Mirror, Nostalgia, etc.) explore memory, time, and spiritual longing through dreamlike imagery and personal recollection. Hatami never saw international fame like Tarkovsky, yet in Hezardastan or Sooteh-Delan one finds a Tarkovskian imprint: the use of long, meditative takes, the interweaving of personal memory with historical destiny, and a certain reverence for the past’s hold on the present. Tarkovsky once observed, “In a certain sense the past is far more real, or at any rate more stable, than the present. The present slips and vanishes like sand between the fingers, acquiring material weight only in its recollection.” Hatami’s entire filmography echoes this belief – that only through memory (through recollection, whether personal or collective) do we find reality’s weight and meaning. Like Tarkovsky, who would include his father’s poems in Mirror, Hatami includes the cultural poetry of Iran in his narratives to anchor them in a timeless human experience. Both men also infused their cinema with spirituality: Tarkovsky’s Russian Orthodox spirituality takes a more abstract, metaphysical form, whereas Hatami’s spirituality is colored by Persian mysticism and love for cultural rituals. One could say Hatami was “sculpting in time” in his own way, using Iran’s cultural symbols as his clay.

Then there is Akira Kurosawa, the great Japanese filmmaker, whose epics like Seven Samurai and Ran brought Japan’s history and legends to life with sweeping grandeur and moral clarity. Kurosawa often adapted Shakespeare and Japanese folklore, translating them to film with visceral power. Hatami, though on a very different canvas, did something analogous: he adapted the essence of Persian literary classics and historical chronicles into his films. Just as Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood brilliantly transposed Macbeth into a samurai tale, Hatami’s Hezardastan transposes the archetypal struggle of good vs evil (and the seduction of power) into a distinctly Iranian context, reminiscent of the tragic turns in Shakespeare’s plays but set in the backstreets of Tehran. Both directors are known for ensemble casts and rich period detail, and indeed Hatami’s coordination of dozens of characters and extras in Hezardastan rivaled Kurosawa’s battle scenes in complexity (albeit on a different scale – battles of intrigue, not armies). Kurosawa once said, “The role of the artist is never to look away.” Hatami similarly confronts the truth of his society’s history – he does not look away from unpleasant truths (like corruption, or the role of foreign powers in Iran’s woes) even as he lovingly recreates the beautiful aspects of that history. Both filmmakers’ works converge stylistically too: Kurosawa’s use of nature’s elements (rain, wind, fire) to heighten drama finds a parallel in Hatami’s use of cultural elements (music, architecture, language) to enrich narrative. One might even imagine Kurosawa admiring Hatami for doing for Iran what he did for Japan – forging a cinema of national essence with universal appeal.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, the Italian polymath, offers another illuminating comparison. Pasolini was a poet, novelist, and filmmaker who often drew on classical or folk texts – from Greek tragedy (Oedipus Rex, Medea) to medieval tales (The Decameron, Canterbury Tales) – infusing them with contemporary social commentary and a raw, earthy cinematic style. Hatami, too, was a multi-disciplinary talent (he wrote, directed, designed) and found inspiration in the classics. Both were fascinated by the intersection of the sacred and the profane: Pasolini’s films juxtapose the sublime (religion, myth) with the gritty (earthly lust, poverty), and Hatami frequently does the same by placing something pure (a piece of poetry, a noble character) amidst the messiness of life. For instance, Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew retells the Christ story with neorealist simplicity – Hatami’s Hezardastan retells a segment of Iran’s “gospel” (its formative early-20th-century ordeal) with a blend of realism and allegory. Stylistically, Hatami was not as provocatively avant-garde as Pasolini, yet he was similarly uncompromising in his vision and often at odds with censors. Both men met obstacles: Pasolini with censorship in Italy, Hatami with bans in Iran (as with Hajji Washington). Yet each persisted in using cinema as a means of exploring cultural identity and morality. Pasolini once remarked that the more personally and culturally specific a film is, the more it reaches the universal – a truth clearly borne out by Hatami’s work, which, though steeped in Iran, speaks to anyone about preserving one’s heritage amid change.

We might also draw a parallel between Hatami and literary figures like Jorge Luis Borges. Borges, the Argentine writer, filled his stories with labyrinths, mirrors, and imagined books that blend reality and fiction, often commenting on history and myth. Hatami’s Hezardastan is structured almost like a Borgesian labyrinth – stories within stories, a narrative that folds back on itself through flashbacks and revelations, and a play on the idea of history as an intricate design only fully seen from above. There is a scene in Hezardastan where an old detective lays out dozens of newspaper clippings on a table, trying to connect dots of a grand conspiracy – it is very much like a Borges story where a detective might realize he is part of the very plot he investigates. Borges was obsessed with how fiction and reality interpenetrate, writing for example: “We live our lives influenced by fictions – we are perhaps all a fiction.” Hatami similarly blurs fiction and reality: by populating Hezardastan with both fictional characters and real historical figures (politicians, ministers), he invites the viewer to consider how history is itself a kind of storytelling agreed upon, and how the individual lives lost in official history still matter. Like Borges’s Pierre Menard who re-wrote Don Quixote word for word in another era to give it new meaning, Hatami “re-writes” Iran’s history in cinematic form, yielding new insights as context shifts.

At the mystical heart of Hatami’s influence stands Rumi. If one name in world culture resonates through Hatami’s work, it is Jalaluddin Rumi, the 13th-century Sufi poet whose ideas of love, unity, and the illusory nature of worldly divisions seem to animate the ethical core of Hatami’s storytelling. Hatami’s characters often undergo what could be called a Sufi arc: a journey from egoism or naiveté to enlightenment or selflessness. Reza in Hezardastan transforms from an angry young avenger to a peaceful sage; the siblings in Mother overcome petty quarrels in face of mortality; even the flippant Jafar Khan in Farang eventually feels the tug of home and authenticity. Rumi wrote, (“Out beyond ideas of infidelity and faith, there is a vast field – and we long for that expanse”). This famous idea of unity beyond duality is mirrored subtly in Hatami’s approach: he tries to bridge secular and sacred, past and present, East and West. In his work, the distinctions (while respected) ultimately dissolve into a larger humanistic vision. For instance, Delshodegan presents music – often deemed secular and suspect by hardliners – as a sacred bridge to the divine and to collective identity; Hatami effectively argues that what might seem profane (earthly love, art) is profoundly sacred if seen with the right eyes. One can almost hear an echo of Rumi’s lines in Hatami’s scenes where people of different backgrounds (cleric, soldier, singer, dervish) sit together appreciating a poem or a song, momentarily forgetting all differences. There is mysticism not only in Hatami’s content but in his form – his penchant for gentle repetition of motifs, circular narratives, and yes, poetic rhythm. Many of his film sequences feel like whirling with the camera, akin to a dervish’s dance around the truth unspoken at the center.

And finally, one cannot ignore the resonance with William Shakespeare. Shakespeare is arguably the world’s greatest dramatist of human nature, and Hatami in his sphere attempted a similar exploration for his culture. The layers of intrigue in Hezardastan – with its betrayals, hidden identities, feigned madness (one character pretends to be insane to escape punishment) – bring to mind Shakespearean plots from Hamlet to King Lear. Hatami’s deep empathy for all his characters, even the flawed ones, also recalls Shakespeare’s ability to imbue each figure with humanity. For example, Khan Hezardastan, though the antagonist, is shown in a vulnerable moment mourning his lost youth and country, not unlike Shakespeare’s nuanced portrayals of kings and villains who soliloquize on the hollowness of power. Hatami’s dialogues, especially in Hezardastan, have a theatrical flair and rhythm – at times characters speak in proverbs or rhyming retorts as if delivering mini-soliloquies. His works combine the comic and tragic in the same Shakespearean spirit: consider Hajji Washington, which like a Shakespearean tragi-comedy starts in almost farcical tones and ends in poignant solitude; or Mother, where comedic family bickering gradually gives way to tearful reconciliation. Both Hatami and Shakespeare often break the barrier between performance and life – Shakespeare with his famous line “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players,” and Hatami by literally constructing a life-sized stage of old Tehran in Ghazali and having real life and performance intermingle there. In a sense, Hatami made Iran itself the stage and player in his dramas. To paraphrase Shakespeare, what a stage hath Hatami built, and what players be his characters! Through them, the fundamental themes of love, power, betrayal, honor, and memory play out – themes that are as Iranian as they are universal.

Ali Hatami’s cinema, then, stands at a confluence of influences and yet remains entirely original. He was a dreamer with a blueprint, a nostalgic and a reformer, both delshodeh (in love) with Iran’s past and daring in reimagining it. In a period when much of “serious” Iranian cinema (especially post-revolution) moved towards minimalist realism and social commentary in contemporary settings, Hatami swam against the current by indulging in opulent set pieces and period drama. Some critics abroad, unfamiliar with the nuances of Persian culture, dismissed his films as overly sentimental or nationalist. But within Iran, viewers understood that Hatami’s sentimentality was the genuine affection of a son for the motherland, not jingoism; and his nationalism was one of cultural richness, not political chauvinism. He did not make films to win festival awards or please critics – he made them to speak to his people, much in the way a poet composes verses for kindred souls.

Indeed, Ali Hatami can be thought of as a modern-day hekmats-goo (sage) or naqqal (storyteller) in the lineage of those who kept Iranian culture alive through oral recitation and writing. He just happened to use camera and film reels instead of a carpeted corner and a book. There is a scene described in an interview where Hatami, on the nearly completed set of Hezardastan, recited verses of Ferdowsi and began to weep softly – as if sensing that through his efforts the ghosts of Iran’s past had found a voice again. In that moment, one might recall Ferdowsi’s own claim after thirty years of labor on the Shahnameh: – “I resurrected the Persian (spirit) with my Persian verse.” Hatami, across roughly thirty years of artistic work (1967–1996), resurrected many an aspect of the Persian spirit– with his cinema. If Ferdowsi gave Iran an immortal epic in words, Hatami gave Iran an immortal epic in sights and sounds.

Let us end with an image, a poetic tableau as Hatami himself might have staged: We see an old teahouse in Tehran at dusk. The year is indeterminate – it could be 1940 or 2025, for in this teahouse time bends. On the wall hangs a portrait of Ferdowsi, and beneath it a radio softly plays a song of Delkash from the 1950s. In a corner, a few men sit around a qalyan (water pipe), discussing the day’s news, while a young couple in the opposite corner shyly share a cup of tea. By the window, under the fading light, sits Ali Hatami with a thick notebook of script pages and sketches. He is conversing in low tones with Hafez, whose words he borrows for a line of dialogue; Sa’di is there too, nodding in approval as Hatami includes a moral couplet of his; Rumi chuckles and spins a little whirl as Hatami inserts a mystical metaphor; Ferdowsi claps Hatami on the back, pointing out a detail of the set design that echoes a scene from ancient Khorasan; Attar listens quietly, stroking his beard, recognizing that the journey of Hatami’s characters mirrors the Conference of the Birds. In another seat sits Tarkovsky, smiling faintly as he raises a glass of tea in toast to this Iranian kindred spirit; Kurosawa pours another cup for Hatami, both understanding each other’s devotion to historical truth; Pasolini winks and says, “You have your Canterbury Tales, I have mine;” Borges peers through his spectacles at the script, appreciating the labyrinthine plot; and Shakespeare, somehow present in translation, exclaims “By the pricking of my thumbs, something poetic this way comes!”

Of course, this scene is a fancy – a little imaginative reward to the man who rewarded us with so many imaginings. But in truth, all those voices were present in Ali Hatami’s mind and work. He carried a universe of culture within him and translated it to cinema with rare finesse. As the gathering in our imaginary teahouse breaks up, perhaps Hatami himself would recite, softly, a fitting couplet from Hafez:– “He whom love has quickened will never die; our eternity is inscribed in the cosmic ledger.” Hatami’s love – for Iran’s people, its letters, its melodies, its memories – keeps him alive, eternal, inscribed in the ledger of culture. In the continuous essay of Iranian art, his chapter is indelible and glowing.

Ali Hatami’s life and vision remind us that cinema, in the hands of a poet, can become much more than entertainment – it becomes a vessel of cultural rebirth and philosophical inquiry. His films reinterpret and reimagine Iranian literature, culture, and philosophy not as relics under glass, but as living, breathing experiences that speak to each new generation. Through him, the classical Persian literary tradition found a new stage; through him, mysticism found modern metaphors; through him, the oral storytelling of bazaars transformed into the visual splendor of film; and through him, Iran saw itself – past, present, and perhaps even future. In an era of rapid change and identity crises, Hatami’s art reassured a nation of its continuity. Historical memory, he taught us, is a light that must never be dimmed. And truly,– the true lamp never goes out. As long as an Iranian somewhere hums an old melody from Delshodegan, or quotes a line from Hezardastan, or smiles remembering Hasan Kachal, Ali Hatami’s lamp burns bright. His cinema of a thousand tales now itself joins the timeless anthology of Persian lore.