Albert Camus famously wrote of the mythic Sisyphus that “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” . In the cinema of Sohrab Shahid-Saless, this philosophical injunction echoes through images of ordinary people performing seemingly meaningless tasks day after day under an indifferent sky. Shahid-Saless’s films linger on the slow turning of the everyday: an old railway switchman repeatedly aligning tracks for passing trains, a young boy wordlessly tending to chores by the Caspian Sea. In these quiet, unadorned moments, his work finds a profound, poetic resonance. The viewer is invited into a meditative contemplation of time, memory, and the human condition – an experience at once deeply philosophical and quietly emotional. Shahid-Saless’s cinematic vision is as theoretical as it is poetic: a sustained inquiry into existence and social reality, rendered in an austere, minimalist style that has led critics to describe his cinema as “implacably slow” and “minimalist” , yet burning with understated intensity. Indeed, beneath the muted colors and nearly mute heroes of his films lies a core of smoldering indignation – “anger burns below the cool surface” of his scenes of everyday life, a testament to the injustice and alienation he so patiently observes. Shahid-Saless’s art is one of melancholia and memory, shaped by his own life of exile and displacement, yet it is also suffused with a quiet humanism, a belief that by gazing unflinchingly at life’s most simple events one may glimpse something universal and enduring.

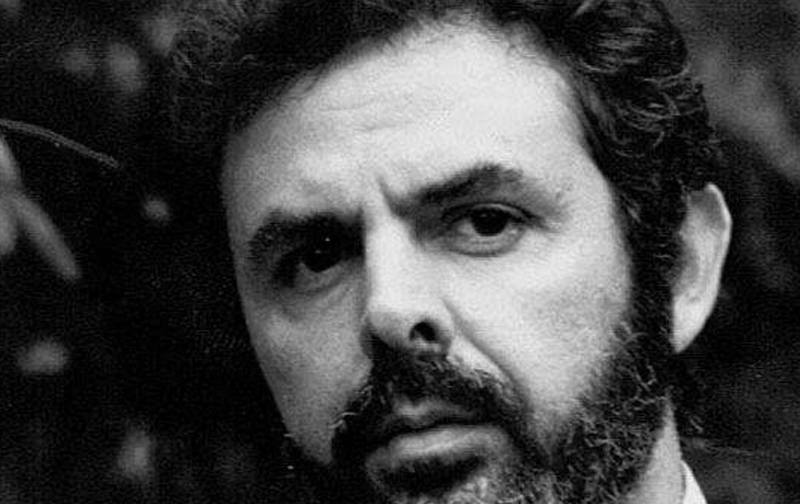

Born in 1944 in Qazvin, Iran (then a part of a country on the cusp of tumultuous change), Shahid-Saless came of age in a world of dislocation . He studied film in Austria and France in the 1960s , absorbing the lessons of European art cinema and postwar existential thought, before returning to Iran to apply his craft. From the beginning, his sensibilities set him apart from the popular Iranian cinema of the time. In Iran of the late 1960s and early 1970s, the dominant commercial fare – known as Filmfarsi – was awash in melodrama, fantasy, and formulaic storytelling. Shahid-Saless became part of a burgeoning counter-movement, the Iranian New Wave, which sought to replace those escapist fantasies with a “reality of ordinary people’s lives, treated with empathy and respect” . As film scholar Hamid Naficy notes, Shahid-Saless emerged as “the most loyal dramatist of naturalism and realism in Iranian cinema.” His approach exemplified the New Wave’s foundational features: reality – a faithfulness to the textures of the external world – and realism – a commitment to the stylistic conventions of classic realist cinema . These intertwined principles set New Wave films like his apart from the “fantasy-driven and narratively chaotic” plots of mainstream cinema . Instead of sensational action, Shahid-Saless offered what Italian neorealist critics once called “luminous truth” : a clear-eyed portrayal of life’s simple, luminous details, through which deeper truths about society and humanity quietly reveal themselves.

Working initially as a documentary filmmaker for Iran’s Ministry of Culture and Art in the late 1960s , Shahid-Saless honed his observational eye on short films about folklore and daily rituals. This documentarian’s patience and respect for reality carried into his first feature film, A Simple Event (1973). Made on a shoestring budget and shot clandestinely with non-professional actors, A Simple Event is emblematic of Shahid-Saless’s aesthetic. It follows a few days in the life of a ten-year-old boy, Mohammad, who lives with his sick mother and fisherman father on the shores of the Caspian Sea . Narratively, the film is as spare as its title suggests – virtually “no discernible plot,” as one scholar observed, only the repetitive drudgery of the boy’s quotidian existence . He attends to chores, wanders by the seaside, and witnesses small incidents that scarcely register as drama. And yet, through Shahid-Saless’s patient lens, these mundane moments acquire a haunting poignancy. The film “inspires viewers to respond emotionally to characters seemingly devoid of any feeling themselves” . Long static takes observe Mohammad as he sits silently in class or watches his father at work, inviting us into a state of quiet empathy. When the “simple event” of the title finally occurs – the “sudden and tragic death” of the ailing mother – it is handled with the same understatement as everything else. Shahid-Saless refuses any overt sentimental cues; it is as if this tragedy were just another natural sound in the environment, as ordinary (or as mysterious) as “dogs barking and crickets chirping” in the night . By leveling the distinction between the profoundly tragic and the banally everyday, the film challenges our narrative habits. In this minimalism lies a radical vision: life’s meaning is not in grand plot points, but in the accumulation of small moments and the feeling they quietly evoke.

A Simple Event announced Shahid-Saless on the world stage – it was recognized as a breakthrough in Iranian art cinema – and it also had a deep impact on fellow filmmakers. A young Abbas Kiarostami, who would himself become an iconic auteur of Iranian cinema, saw A Simple Event and “felt an artistic epiphany” . Armed with a new sense of possibility from Shahid-Saless’s example , Kiarostami soon made his own first feature, adopting a similar focus on a child’s perspective and everyday milieu. Kiarostami’s subsequent works continued the path of neorealist simplicity and open-ended observation that A Simple Event had trailblazed. That one quiet film by Shahid-Saless – largely devoid of overt drama – could ignite the imagination of Iran’s next great filmmaker speaks to its almost spiritual impact. Shahid-Saless’s approach, as Kiarostami and others recognized, represented a new way of seeing: a poetic cinema of reality that finds lyricism not in elaborate artifice but in authenticity and attentive presence. (Here one hears an echo of the French critic André Bazin, who wrote that cinema at its best “reveals the enigmatic character of the real” and allows us to re-capture a child’s sense of awe in the everyday . Shahid-Saless’s cinema answers precisely to that description.)

If A Simple Event was an intimate sketch of childhood and loss, Shahid-Saless’s next major film, Still Life (1974), expanded his vision into a quietly devastating social portrait. Still Life (Ṭabiʿat-e bijān) follows an elderly railway switchman, Mohammad Sardari, who has spent decades tending a tiny rail stop in a remote desert area . Each day, Sardari’s simple duties are the same: he manually lowers and raises a rail-crossing barrier and adjusts the tracks for infrequent passing trains . He lives in a modest, box-like house by the tracks with his wife, who weaves carpets to supplement their meager income . Shahid-Saless uses this exceedingly sparse scenario to craft what critic Tina Hassannia calls “an eminently poignant exercise in existential temporality, framed with a neo-realist simplicity.” The film’s form is rigorously minimalist: long, static takes, often from low camera angles, observe the “quotidian mundaneness” of Sardari’s routine with painstaking patience . We watch him sit, eat a simple meal, smoke his pipe, or wind his old wall clock. Dialogue is scarce, and dramatic events even scarcer. Yet far from being boring, this deliberate slowness accumulates an almost hypnotic power. The tedium of Sardari’s life is depicted with elegance – the austerity of the images, the rhythmic repetition of tasks – such that the viewer begins to feel the weight of time as Sardari feels it . Shahid-Saless achieves something remarkable: he makes time itself the true protagonist of the film, stretching and sculpting it within each long take.

In Still Life, time is at once Sardari’s companion and his adversary. In one sense, he has an abundance of time – his days are slow and empty, filled with idle hours between train crossings. Yet he is also ruled by time in an absurd way: after a lifetime of service, he is abruptly informed that he is being retired, cast aside like an obsolete cog in the machinery of the railway . This event displaces him not only from his job, but also from the very identity and routine that sustained him. The news arrives wordlessly, in the form of a letter, and Sardari’s confusion is profound. In one quietly heartbreaking scene, he travels to a bureaucratic office in the city to protest the decision, only to face a Kafkaesque runaround: officials send him from one desk to another until he is told the decision is final . There is no concern for his livelihood, no talk of pension; like so many of Shahid-Saless’s protagonists, Sardari is simply ignored by the system that should have cared for him. The film shows him returning home, where a younger man has already arrived to replace him at the rail station – an almost absurd intrusion. In a wordless gesture of forlorn hospitality, the old man invites his replacement into his home for tea, as if hoping to preserve a shred of dignity or normalcy . It is an “absurd moment,” as one commentator noted, suffused with both politeness and pathos . Sardari continues to wake up and perform his duties alongside the new guard for a time, as if unable to comprehend that his role in life has evaporated . Shahid-Saless treats these developments without overt sentiment; the emotional impact comes precisely from the matter-of-fact depiction of Sardari’s quiet despair and disorientation.

Still Life keenly illustrates the themes of alienation and exploitation that run through Shahid-Saless’s oeuvre. On the surface, Sardari’s life seems to exemplify humble contentment – a still life of simple patterns. But Shahid-Saless reveals how this apparent simplicity masks deeper currents of loss and injustice. The film’s title itself hints at a double meaning: still life as in an artfully arranged tableau of objects (indeed, many shots resemble austere still-life compositions), but also life that has become stagnant or lifeless. Sardari is a man caught between eras and systems – “displaced by time” even before he is officially pushed out . He works for the railroad, a symbol of modern industrial progress, yet he lives like a peasant of the past, in a rhythm closer to that of the sheep herds that occasionally wander across his tracks . (In one quietly symbolic scene, a flock of sheep slowly crosses the railway, the modern and the pastoral intersecting in a long take that “luxuriates” in the visual metaphor .) The Iran of the early 1970s was in the midst of the Shah’s modernization drive, caught between tradition and modernity, and Still Life subtly critiques the “liminality” of that condition . Sardari’s fate – discarded without support – reflects the dehumanizing side of rapid modernization. He is exploited and ignored by the economic system, left to fend for himself once deemed useless, much like the exploited workers in other Shahid-Saless films . Imogen Sara Smith observed that Still Life “gazes unblinkingly at [a] working man who [is] exploited, discarded, and above all ignored by callous economic systems.” Indeed, beneath the placid surface of Shahid-Saless’s minimalist style is a simmering critique of social injustice – a moral outrage expressed in the quietest of cinematic whispers.

For Western critics, Still Life solidified Shahid-Saless’s reputation as a master of “slow cinema” avant la lettre. The film was honored at the 1974 Berlinale (winning the Silver Bear for outstanding artistic contribution) , signaling that world cinema was beginning to recognize the unique voice emanating from Iran. Shahid-Saless’s style in these early works invites comparison with other filmmakers who use slowness and austerity to philosophical effect. One might think of Robert Bresson in France, whose films like Mouchette (1967) or Au Hasard Balthazar (1966) also focus on marginalized figures (a peasant girl, a donkey) and elicit profound empathy through spare means. Bresson insisted on stripping cinema of ornament and using non-actors to achieve a kind of transcendental realism; Shahid-Saless, though not overtly spiritual in the way Bresson could be, shares this commitment to minimalism and truth. His actors, often untrained locals, perform with a subdued, deadpan quality that recalls Bresson’s famous “model” style – an affectless delivery that paradoxically allows genuine emotion to emerge in the viewer. When watching Still Life or A Simple Event, one might recall Bresson’s admonition about viewers who dismiss challenging art with “I don’t like it, it’s boring!” – an exclamation Bresson (and Tarkovsky after him) likened to a blind man disdaining a rainbow . Andrei Tarkovsky, another giant of the poetic cinema, defended slow, contemplative filmmaking by saying that those who call such art “boring” are often “not willing to consider the meaning of their existence,” masking a spiritual emptiness with that vulgarly simplistic cry . Shahid-Saless’s films, much like Tarkovsky’s, demand a certain patience and openness from the viewer; in return, they offer a rare intimacy with reality and time that can be profoundly illuminating. “Time is a state,” Tarkovsky wrote, “the flame in which there lives the salamander of the human soul.” Few filmmakers have stoked that flame of time on screen as tenderly as Shahid-Saless. In his long takes of clocks ticking and fires dying in Still Life, we experience time not as a mere backdrop for plot, but as the very medium of human existence – something to be felt deeply, even when (or especially when) “nothing happens.”

By 1975, having made only two features in Iran (A Simple Event and Still Life), Shahid-Saless found himself at a crossroads. The political and cultural climate in Iran was growing more repressive for independent artists. Even before the 1979 revolution, there were pressures – censorship, difficulties obtaining resources – that made it hard for Shahid-Saless to continue his kind of uncompromising filmmaking. His response was essentially an exodus: like many Iranian intellectuals and filmmakers of his generation, he left the country to work abroad. In 1976 he emigrated to West Germany , joining a wave of Iranian diaspora filmmakers who sought creative freedom in exile. Hamid Naficy has noted that since the 1960s, Iranian filmmakers in diaspora have formed one of the most active transnational cinema groups . Shahid-Saless became a prime example of this “accented cinema” of exile : his identity as a filmmaker evolved from Iranian new-wave auteur to cosmopolitan émigré working in multiple languages and contexts. Yet even as his circumstances changed, his thematic preoccupations – time, alienation, social critique – remained remarkably consistent. In fact, displacement and exile would become increasingly central subjects of his films once he was working in Europe. If his Iranian films gently revealed the estrangement of individuals within their own land, his later films would often tackle the literal estrangement of immigrants and outcasts in a foreign society. Shahid-Saless’s oeuvre thus bridges two worlds – early 1970s Iran and late 20th-century Europe – but it maintains a cohesive vision, unified by what he himself described as an effort to document “the antagonism between man and society” and to “make [people] conscious of the indignity and inhumanity of life.” These were Shahid-Saless’s own words about his cinema, and they underscore the humane yet unflinching philosophy guiding his work. Whether in Persian villages or German cities, he kept his camera trained on those whom society treats with indignity – the economically oppressed, the socially invisible – illuminating their plight with a steady, compassionate gaze.

Shahid-Saless’s first project in Germany was Far from Home (1975), a film significantly titled to reflect dislocation. Interestingly, Far from Home was an Iranian-produced film (shot in Persian) but set among immigrant workers in Germany – a harbinger of the director’s own impending move. The film, featuring Iranian actor Parviz Sayyad alongside Turkish–German cast, depicts the lives of Turkish “guest workers” in 1970s West Germany. These characters are literally far from their homeland, laboring in a society that exploits their work while marginalizing their lives. Far from Home extends Shahid-Saless’s compassionate realism to a transnational context: it “gazes unblinkingly” at migrant laborers who face economic exploitation and cultural isolation . The anger at injustice which simmered under the surface in Still Life becomes, if not louder, at least more transnational in Far from Home. It won the FIPRESCI Prize at the 1975 Berlin International Film Festival , indicating that international critics recognized the film’s incisive gaze on migrant experience. In a way, Far from Home serves as a thematic bridge between Shahid-Saless’s Iranian period and his exile period: it carries the Iranian new wave’s concern for the downtrodden into the realm of the immigrant narrative, presaging the director’s own journey of exile.

Settling in West Germany, Shahid-Saless continued to work in television and film through the late 1970s and 1980s, crafting a series of German-language works that remain unjustly lesser-known. Yet these films are an essential part of his oeuvre, further developing his distinctive style and concerns. One of the earliest, Time of Maturity (Reifezeit, 1976), was among his first German productions . It tells the story of a young boy, Michael, in a West German town, who saves money to buy a bicycle by running errands for a blind neighbor – all while his single mother secretly works as a prostitute to support them . In Time of Maturity, we see Shahid-Saless returning to a child’s-eye perspective (as in A Simple Event), but now transposed to a European social context. The film gently explores the boy’s coming-of-age amid economic hardship and maternal sacrifice. The mother’s concealment of her sex work to protect her son’s innocence introduces a theme of hidden sorrow and dignity, much as the boy in A Simple Event quietly endures poverty and loss. Shahid-Saless’s restrained direction in Time of Maturity earned it critical notice – it premiered at Locarno in 1976 and received an honorable mention from the Ecumenical Jury , indicating its humane values were appreciated.

Another notable work is Diary of a Lover (Tagebuch eines Liebenden, 1977), which, as the title suggests, is an introspective piece likely structured as a personal chronicle. (In a 2019 essay, scholar Kumars Salehi analyzed Diary of a Lover and Time of Maturity together as studies in “alienation and the everyday” in Shahid-Saless’s work .) While details on Diary of a Lover are scarce, the title evokes a private, phenomenological approach – perhaps a lonely man’s diary, implying subjective time and memory. It is intriguing to think of Shahid-Saless, an exile at this point, delving into the inner life of a “lover” in a diary format: likely a continuation of his interest in isolation and the passage of time, but framed through an intimate first-person lens.

By the end of the 1970s, Shahid-Saless embarked on two ambitious television films that further revealed the breadth of his interests: The Long Vacation of Lotte H. Eisner (1979) and The Last Summer of Grabbe (1980). The former is particularly fascinating – Lotte H. Eisner was a real historical figure, a renowned German film archivist and critic (and a Jewish exile from Nazi Germany). Shahid-Saless making a film about Eisner suggests a deep self-reflexivity: an exile filmmaker portraying the life of another exile (one who, like him, bridged cultures and had an enormous love for cinema’s heritage). Little is commonly written about this film, but one can surmise it was a kind of docu-fiction, perhaps a quiet tribute to Eisner’s solitude and intellect, rendered in Shahid-Saless’s contemplative style. Grabbe’s Last Summer similarly takes a historical/literary figure – the 19th-century German playwright Christian Dietrich Grabbe – and imagines his final days. These works indicate Shahid-Saless’s expanding range: from contemporary poor Iranians and Turkish immigrants to European cultural figures. Yet even in these historical pieces, one imagines he gravitated toward themes of mortality, memory, and the inner struggles of his subjects (Eisner’s “long vacation” perhaps metaphorical for her later years in exile; Grabbe’s last summer marked by illness and neglect). It is as if Shahid-Saless were seeking kindred spirits across time – other souls grappling with displacement or unfulfilled aspirations, whose experiences he could empathize with and bring to the screen with his trademark restraint.

In 1980, Shahid-Saless directed Ordnung (Order), which was entered into the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes that year . Ordnung is a dark, off-beat psychological drama about a man named Herbert who abruptly quits his job and spirals into apathy and indifference towards society . Critics have noted that Ordnung dissects German post-war ennui and the feeling of meaninglessness that can overtake an individual within a rigid social “order.” The protagonist’s refusal to continue participating in the workaday world – and the cold response he meets – align perfectly with Shahid-Saless’s enduring interest in characters who reject or are rejected by society’s norms. Herbert’s quiet rebellion (simply dropping out) may be seen as another Sisyphus laying down the boulder. But unlike Camus’s Sisyphus, who finds meaning in ceaseless effort, Herbert is a figure of exhaustion – his freedom acquired through stepping away from roles and rules, only to confront existential emptiness. Shahid-Saless handles this story, reportedly, with an “off-beat” touch and formal rigor , offering an unvarnished look at a man in spiritual crisis. It’s telling that Ordnung won the Silver Hugo at the Chicago Film Festival and was recognized in Cannes – evidence that Shahid-Saless’s work, while austere, was deeply respected on the international circuit for its integrity and insight.

The culmination of Shahid-Saless’s German period is often considered to be Utopia (1983), his longest and arguably most challenging film. Utopia is a 186-minute epic set not in a pastoral Iranian village or a quiet provincial town, but in the grim underbelly of urban society – it is “the tale of a pimp and his five [prostitutes]” in a West German city . Critics described Utopia as a “hard ghetto film” for its unflinching, nearly documentary-like examination of sex workers and their abusive pimp, focusing on the power dynamics and desperation in their lives. If Shahid-Saless’s earlier films dealt with subtle exploitation (a railwayman discarded, a child neglected), Utopia tackles exploitation in its most overt form: the commodification of bodies under capitalism’s direst conditions. Yet Shahid-Saless approaches this harrowing subject with the same slow, observational style he applies to a boy fishing or an old man sipping tea. The result is a film that avoids sensationalism entirely; instead, it coolly, patiently exposes how systemic forces trap these women in cycles of dependency and submission. In one analysis, Utopia has been interpreted as a study of “sex work under capitalism”, where the pimp’s method of control is to pit the women against one another to ensure their loyalty and despair . Shahid-Saless spent years trying to get Utopia made (it was a difficult production to finance and organize, understandably given its length and content). When it finally premiered at the 1983 Berlin Festival , it stood as a formidable statement: a cri de coeur about human degradation that still maintained the director’s signature remove – cool, measured, but seething beneath. One contemporary reviewer observed that Utopia’s characters are nearly as taciturn as those in Shahid-Saless’s earlier films, moving through “muted” urban spaces with a kind of numb routine, even as “anger burns below the cool surface” . In this way, Utopia ties back to the director’s constant concern: the indignity of life in an unjust society, and the challenge of remaining human in the face of it. If Still Life showed a man denied dignity by modernization, Utopia shows women denied dignity by patriarchal exploitation and poverty. Both films, vastly different in milieu, convey what Shahid-Saless saw as cinema’s purpose – “to make conscious” the structures of inhumanity around us .

Throughout these later works, Shahid-Saless also continued to demonstrate a phenomenological attention to the textures of experience. Even as his narratives ventured into more explicitly socio-political territories (immigration, sex work, historical biography), he never abandoned the slow, patient style that asks the audience to live in time with the film. This aligns with trends in what critics now term “Slow Cinema”, a loose movement including filmmakers like Chantal Akerman, Béla Tarr, Abbas Kiarostami, Tsai Ming-liang, and others who employ long takes and minimal narrative to foreground the act of waiting, the feeling of duration, and the presence of real time. Shahid-Saless can rightly be seen as a forerunner of this trend. In fact, one might compare his work fruitfully with that of Chantal Akerman. Akerman’s masterpiece Jeanne Dielman (1975) famously watches, in real time, a woman performing domestic chores in her kitchen, day after day, to the point that the “rich complexity of daily experience” is revealed through prolonged observation . “Time passes and it’s good to stare at what’s in front of us,” wrote one critic of Akerman’s cinema, noting that if we look long enough, “the rich complexity of our daily experience will reveal itself” . These words could just as well describe Shahid-Saless’s art. He gives us the chance to gaze – to really look at ordinary people and settings – until we begin to perceive layers of meaning and emotion that more fast-paced films would rush past. In both Akerman and Shahid-Saless, this gazing is not a neutral or purely aesthetic act; it carries a political and philosophical weight. By forcing the viewer to spend time with an overlooked person – a housewife, a railway guard, a prostitute, a lonely child – these directors restore a kind of dignity to their subjects and implicate the viewer in their lives. There is a latent radical humanism in such a method. It accords with Martin Heidegger’s idea that in moments of profound boredom or stillness, we confront the reality of Being itself. Heidegger, in his musings on “waiting for a train in a provincial station,” observed that when we are undistracted by stimuli and just experience time passing, “time pushes down on us” and we become keenly aware of our own existence and insignificance . This “uneasy” awareness can be frightening – “most of us are not capable of dealing with raw time,” and we often flee into distractions rather than face the “vacuum” that yawns open in such moments . Shahid-Saless’s films, however, gently insist that we do not flee – that we stay in that station with his characters, listening to the wind or the ticking clock, and confront the raw time of their lives. In doing so, we share in a kind of phenomenological inquiry: we start to feel, almost bodily, what it is to exist in these circumstances. We hear the silence, we sense the boredom and the longing that pervade the screen. Shahid-Saless thus transforms cinema into a tool for reflecting on time and meaning, much as Heidegger suggested profound boredom can paradoxically become a “key to finding meaning” by revealing our existential situation .

The existential dimension of Shahid-Saless’s work invites further dialogue with thinkers like Camus and Sartre. Camus’s notion of the absurd – the divorce between our human need for meaning and the world’s indifferent silence – is almost visually enacted in Shahid-Saless’s narratives. In Still Life, for instance, Sardari’s entire being is oriented around a job that, in the end, meant nothing to those who employed him. When confronted with forced retirement, he faces what Camus described as “the ridiculous character of that habit, the absence of any profound reason for living, the insane character of that daily agitation” . For years Sardari continued making the gestures commanded by existence, as Camus puts it – he wound the clock, aligned the rails – purely out of habit and duty. Now stripped of these routines, he stares into the void of purposelessness, much like Camus’s Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain. Camus wrote that when the illusion of meaning falls away, “man feels an alien, a stranger. His exile is without remedy since he is deprived of the memory of a lost home or the hope of a promised land.” Shahid-Saless’s protagonists often embody this very condition of exile and estrangement, whether literally (as immigrants or refugees) or metaphorically (alienated within their own homes and jobs). They are strangers to the dominant order of things, lacking either nostalgia or utopian hope – much like Camus’s absurd man. And yet, in Camus’s philosophy, acknowledging the absurd is not an end but a beginning. The tragic consciousness of life’s absurdity can give rise to a form of defiant joy or “rebellion” – hence his famous imagining of Sisyphus happy at his eternal labor . Do Shahid-Saless’s films offer any analogous moments of grace or rebellion? In their subdued way, perhaps they do. For instance, in Still Life, after the final, wordless shots of Sardari’s displacement, we see him simply continue with the motions of his life – as if silently refusing to be annihilated by the absurd verdict of retirement. In A Simple Event, the young boy goes back to the shoreline after his mother’s death, casting a fishing line into the sea with stoic resilience. These are small, unheroic acts, yet in their persistence one might glimpse a quiet affirmation of life’s continuance in spite of everything. It is as if Shahid-Saless aligns with Camus’s sentiment that “The struggle itself… is enough to fill a man’s heart” . The dignity of Shahid-Saless’s characters lies in their endurance and routine, which the films portray with respectful attention.

At the same time, Shahid-Saless does not sentimentalize suffering. If anything, his cinema leans more toward the phenomenological than the didactic. He is not lecturing about the absurd or prescribing Camusian heroism; he is showing the condition of absurdity by meticulously depicting everyday life in all its routines and ruptures. In a sense, his films achieve what phenomenologists like Maurice Merleau-Ponty described: a return “to the things themselves,” a bracketing of preconceived narratives to let the essence of lived experience emerge. When we watch one of his long takes – say, the camera lingering on Sardari as he slowly chews his bread in silence, or the boy Mohammad as he sits by his mother’s bedside in dim lamplight – we are invited to be present with these characters, to notice the smallest sounds and gestures, to inhabit their world. This creates a kind of empathetic understanding without words, a transfer of lived experience that is akin to what Merleau-Ponty might call an encounter with the “lived world” of the other. In an era of cinema that often privileges fast editing and overt storytelling, Shahid-Saless’s work remains a powerful reminder of cinema’s ability to capture pure being – to let us experience time flowing, which is arguably one of film’s most philosophical capacities. “Good cinema is what we can believe,” said Kiarostami , and by that measure Shahid-Saless’s cinema is supremely good: we believe utterly in the reality of what we see, no matter how unassuming, because it is presented in its own time and space, without manipulation.

Off-screen, Shahid-Saless’s own life took him further afield in his later years. After the German phase, he eventually moved to the United States, spending his final years in Chicago. He died there in 1998 at the age of 54 – far from the land of his birth, having lived the majority of his career as an exile. This biographical fact – an émigré artist passing away in a foreign country, somewhat in obscurity – adds a poignant coda to his body of work. There is a sense that Shahid-Saless himself shared the fate of the people he depicted: displacement, a certain neglect by the mainstream, but also a quiet resilience through creation. He left behind a legacy of about a dozen features and numerous shorts that, taken together, form a singular chronicle of the human condition across cultures. Yet for many years, his films were difficult to find, almost as “ignored” by the film industry as his characters were by society. Only recently have restorations and retrospectives (such as a 2024 Berlinale Classics program featuring Time of Maturity and the MoMA series on Iranian pre-revolution cinema ) begun to bring Shahid-Saless’s work back into the conversation. Contemporary viewers and scholars are now recognizing him as a pioneer who anticipated trends in world cinema (slow cinema, minimalist narrative, hybrid documentary-fiction forms) well ahead of their time . More importantly, his films are being re-appreciated for their profound humanity and philosophical depth.

Despite the melancholy that undeniably pervades Shahid-Saless’s cinema – the sense of lives weighed down by time and fate – one should not conclude without acknowledging the strangely uplifting effect his work can have. In the very act of observing unseen people and giving weight to their time, his films offer a kind of redemption. There is an ethical dimension to his aesthetics: by watching a poor child’s small struggles or an old man’s daily ritual, we confer dignity on those experiences. Shahid-Saless’s camera, impartial and compassionate, becomes an instrument of witnessing and, implicitly, of solidarity with the downtrodden. It’s as if through his patient lens he is saying: This humble life matters; this unnoticed pain deserves to be seen. That sensibility resonates with Tarkovsky’s view that “art must carry man’s craving for the ideal… must give man hope and faith”, especially when confronting a hopeless reality . “The more hopeless the world in the artist’s version, the more clearly perhaps must we see the ideal that stands in opposition – otherwise life becomes impossible!” wrote Tarkovsky . Shahid-Saless shows us hopeless worlds – worlds of boredom, poverty, injustice – but by doing so with such clear-eyed empathy, he implies their opposite: the ideal of empathy, justice, and human connection. In a subtle way, his films awaken our conscience and our compassion. Tarkovsky also said that the aim of art is to prepare one for death, to “plough and harrow the soul” so that it can turn to what is good and true . Watching Shahid-Saless, one indeed feels the soul being quietly tilled – we are made more acutely aware of “the meaning and aim of [our] existence”, as Tarkovsky put it , by the very patience and concentration his films demand.

In the end, Shahid-Saless’s cinema stands as a bridge between worlds – between Iran and Europe, between East and West, between documentary realism and poetic reverie, between deep political anger and deep spiritual quietude. His stories of time, exile, and everyday life form a unified artistic vision that transcends any one culture. Watching his films, one is reminded of the universality of certain experiences: waiting, longing, working, aging, hoping. These are states of being that any viewer, anywhere, can relate to, if they are willing to slow down and listen. Shahid-Saless invites us to do exactly that. In a contemporary era of ceaseless distraction, his work is a meditative refuge – but also a moral provocation – asking us to bear witness to those on the margins and to find, perhaps, a reflection of ourselves in their silent struggles. There is profound poetry in his cinematic vision, though it is a poetry of the undramatic, the “nearly mute” and the overlooked. It is the poetry of a teapot boiling on a modest stove, of dust motes in a shaft of afternoon light, of a distant train whistle at dusk – moments in which, if we attend closely, we might discern what Rilke called “infinite space” in the small things, or what the Persian poet Forough Farrokhzad described as an entire world reflected in a dew drop. Shahid-Saless’s contribution to world cinema lies in this deep, contemplative seeing. In his work, slowness becomes an act of resistance against the waste of life’s meaning, melancholy becomes an aperture to empathy, and the exile – both the filmmaker himself and the characters he portrays – becomes a kind of Everyman whose condition speaks to our own. Sohrab Shahid-Saless’s life and art ultimately affirm a simple yet profound truth: that by slowing down and facing the reality of our world – its indignities, its quiet beauties – we may rediscover our shared humanity, one long, patient gaze at a time.