In a darkened hall beneath electronic constellations, a lone dervish turns. His white skirt glows with threads of light, each spin casting luminous patterns on the walls. **** In this futuristic vision, the whirling dervish wears illuminated robes under neon stars. The air hums with a digital hymn, yet his eyes are closed in prayer. This is no performance or mere dance – it is an act of devotion. The Sufi Sema, the whirling ceremony, has always been a prayerful meditation, a turning of the body, heart, and soul toward the Divine. Here and now, even amid technological wonders, the dervish’s turning remains dhikr, a remembrance of God, echoing the ancient assertion: “Sema is not dance; it is dhikr (remembrance). We turn with creation, saying ‘Allah’”. In this moment, technology fades to backdrop as the eternal unfolds within the spinner’s heart.

He turns and turns, following a path laid down centuries ago by Jalaluddin Rumi under the inspiration of his mentor Shams-e Tabriz. Rumi’s own heart was set aflame by Shams, a wandering mystic whose arrival in Rumi’s life shattered ordinary understanding and ignited a revolution of love . When Shams disappeared, Rumi’s bereavement poured itself into poetry, music, and the spontaneous whirl of the Sema. “His love and his bereavement for the death of Shams found their expression in a surge of music, dance and lyric poems, Divan-e Shams-e Tabrizi,” recounts one biography of Rumi . The Sema ceremony itself, which Rumi exemplified, became “the most important form of praying” for the Mevlevi Sufis who followed him . It was Rumi’s way of turning grief into ecstasy and motion into devotion. Thus the whirling ritual was born as a living prayer – a “whirling prayer ceremony”, not a performance . To this day, those who carry Rumi’s flame insist that calling Sema a dance misses its essence. One Mevlevi teacher explains that because Sema is an act of remembrance of God, “it cannot be considered [a] dance as such” . The dervish might appear to the eye as a dancer in motion, but to his or her own heart, this turning is an offering, a physical dua (supplication) and zikr in motion.

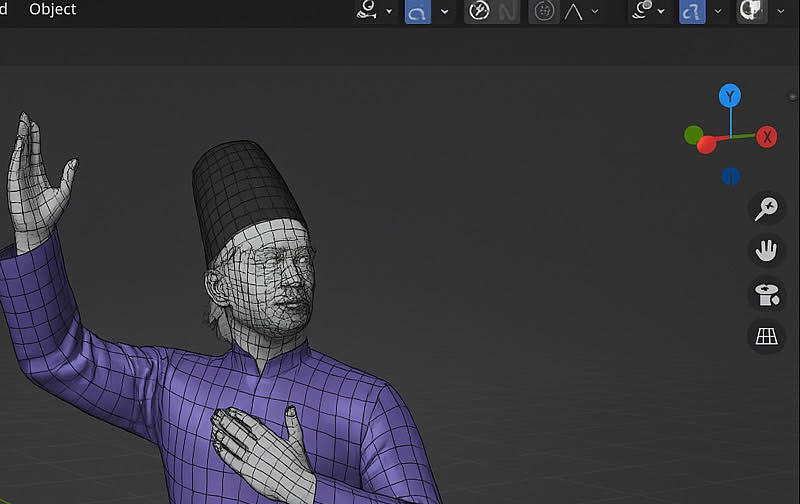

In the traditional Sema, every gesture is laden with meaning. The dervish wears a tall brown hat, a symbol of the tombstone of the ego, and a flowing white gown, the funeral shroud of the ego’s desires. He begins the ceremony by removing a black cloak – casting off the world and stepping into spiritual rebirth. He crosses his arms over his chest, like a corpse at rest, then at the music’s signal he unfolds into life and motion. As the dervish spins, one foot remains rooted to the center, symbolizing stability in the Truth, while the other foot steps around, enabling the perpetual rotation . His right hand extends upward, palm open toward the sky, and his left hand stretches downward, palm facing the earth. In this sacred posture, he becomes a conduit between heaven and earth: “The right hand is turned up towards heaven to receive God’s overflowing mercy which passes through the heart and is transmitted to earth with the downturned left hand,” as one description of the Mevlevi ritual explains . The dervish’s head is inclined slightly to the left, eyes unfocused, as his true gaze turns inward. With each full circle, he softly mouths “Allah”, the Name of the Divine, in time with the music and his steps . In this way, “with every step” he is remembering God . The whirling generates a subtle vortex – a spiral of devotion – which, as Sufi mystics describe, can “allow the possibility for divine inspiration of healing and renewal to enter and spread” through the space . The dervish becomes the still axis at the center of a turning world, focused on unity even as everything around him dissolves into blur. As one Sufi master described it, “imagine seeing the world whirling by, but you are not focusing on all that multiplicity. Instead, you are focused on the oneness and the unity that is being expressed.”

What is this “oneness” that the dervish seeks in turning? It is the oneness of love. Shams Tabrizi – the spiritual sun that melted Rumi’s heart – taught that nothing should distract from the all-encompassing Beloved . For Shams, the presence of God was so complete that he had no need for any artificial states; he was drunk on Divine Love alone . He once exclaimed in poetic metaphor, “Love is the water of life. And a lover is a soul of fire! The universe turns differently when fire loves water.” . Love sets the very cosmos whirling; when the lover (a soul aflame) unites with the Beloved (the water of life), even the stars and planets must dance in a new rhythm. In the turning of the Sema, the dervish seeks to align with that cosmic dance of love. Rumi too, in his own way, spoke of this secret music that moves all things: “We rarely hear the inward music, but we’re all dancing to it nevertheless, directed by the one who teaches us… the pure joy of the sun, our music master.” . In other words, whether aware of it or not, every soul is subtly whirling in the pull of a divine melody. The Sufi simply chooses to hear it, to let it move him in conscious remembrance. In one of his quatrains, Rumi invites us directly into the dance: “As waves upon my head the circling curl, / So in the sacred dance weave ye and whirl. / Dance then, O heart, a whirling circle be. / Burn in this flame – is not the candle He?” . The “candle” is the Divine Light; the heart must burn in that flame and itself become a whirling circle of love. Thus, the whirling ceremony externalizes an inner surrender – the soul’s turn toward God, burning away all separation.

Seen in this light, what outsiders call the “Whirling Dervish dance” is for the initiate a form of prayer as essential as any other worship. “For us Mevlevis, Sema is the most important form of praying,” says Mete Edman, a modern Sufi practitioner and teacher . It even takes precedence, in its context, over the ordinary rituals – not to replace them, but to fulfill their deepest purpose of connecting with the Divine. The 13th-century originators of this practice knew well that formal prayer (salat) and fasting could become empty without Ishq, the fiery love for God. Rumi’s spinning is an attempt to pray with his whole being, to let the body itself “speak” the language of the soul. “Whosoever knoweth the power of the dance, dwelleth in God,” as an old Sufi saying (often attributed to Rumi) goes . The power of the dance is the power of abandoning one’s ego, transcending the mind’s limitations, and entering into mystical unity. In Sema, the dervish dies to the self while alive – each turn shedding layers of selfhood – and is reborn in spiritual communion. No wonder that to the dervishes it is “a journey towards spiritual understanding” and ultimately “union with the Divine” . It is said that when Rumi first whirled in the marketplace of Konya, hearing the goldsmiths’ hammering as though it were the drum of celestial music, he cried out “Allah!” with every strike and spun for hours, reveling in God’s presence in that moment. The tradition holds that Rumi’s feet traced a circle around the heart – a center point on the floor – symbolizing how the path of love ever circles the Heart of Existence, the Divine truth that is at the center of all.

**** A dervish envisions himself bathed in living light as he turns, merging ancient ritual with futuristic aura. In one of the user’s images, a whirling dervish appears in a halo of electric blue and white, his robes trailing light as if woven from stars. This imaginative, technologically infused art captures something profound: the continuity of the spiritual state even as outward forms evolve. The dervish’s face is serene, eyes gently closed, lost in inward vision, while around him digital patterns swirl like galaxies. It is as though the very circuits and neon of the future world have bent into the shape of a devotional dance. The imagery suggests that Sufism can find a home even in a high-tech future – if its essence is preserved. The essence is inwardness, the “turning of the heart” that does not depend on any particular era’s trappings. Just as the dervish in the image glows with both antiquity and futurism, so too might the Sufi path shine in a digital age: a luminous inward turning that uses even technology as a backdrop for transcendence rather than a replacement for it. The illuminated robes in the image recall the light of guidance (nur) that Sufis speak of – here made visible in fiber-optics and LEDs, yet pointing to the same inner Light. In the midst of holograms and augmented reality, the whirling figure reminds us that what matters is the spirit animating the practice. The “sacred atmosphere” is still there; it has simply taken on a new costume. The prayer endures, even if the stage changes.

Yet we must ask: can such a tradition truly survive in a world dominated by screens, codes, and digital abstraction? Can Sufism evolve and remain relevant amid artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and the fragmentation of attention that plagues our era? The challenge is undeniable. Today, many of us live in a perpetual blur of multitasking, our minds spinning not in ecstatic union but in anxiety and distraction. In a sense, the modern human being is already whirling – but whirling in the cyclone of information overload, pulled in a thousand directions by notifications, feeds, and virtual stimuli. This involuntary whirl does not center us; it scatters us. It is here that Sufism’s path of love and silence may be not only relevant but urgently needed. The Sufi way offers an antidote: a deliberate whirling inward, a turning away from the noise. It teaches how to reclaim the fragmented pieces of our attention and reunite them at the heart’s center. In times where attention is currency and solitude is scarce, the very practices of Sufism – slowing down the breath with remembrance, emptying the mind in meditation, focusing the heart in prayerful movement – become revolutionary acts of healing. As one modern commentator notes, we live in a “crisis of consciousness” wherein we struggle to recognize our own true nature amidst constant digital distraction . The remedy, as ever, is to pause, listen, and turn inward to the music of the soul. Even if the world around us has become a cacophony of ring-tones and AI-generated chatter, the inward music still plays softly, waiting for us to hear its melody of unity.

Sufism, at its core, is adaptive because it speaks to the human heart, and the heart’s longing does not diminish with technological advancement. If anything, the more virtual our lives become, the more the soul may yearn for something real, something spiritually tangible. We might witness new expressions of the old whirling ritual: perhaps seekers in virtual reality headsets, meeting in a shared digital semakhana (auditorium) to whirl together across continents. Already, one can imagine a guided VR experience where one dons a suit of sensors and “whirls” in an empty room, while seeing themselves surrounded by fellow dervishes in a simulated 13th-century hall or a fantastic cosmic space. The mind-bending technology of tomorrow could indeed simulate the appearance of Sema – but would the essence be there? The answer depends on the heart of the practitioner. A virtual Sema without love and presence would be hollow, just as a physical Sema without devotion would be mere exercise. Conversely, if the participants approach it with reverence, mindful intention, and a trained focus on God, even a digital gathering could become holy. “Dervish music cannot be written in notes. Notes do not include the soul of the dervish,” say the Mevlevi elders , meaning that the intangible spirit is what makes the practice sacred. Similarly, no high-tech reproduction alone can confer the soul of the experience. The soul is the secret ingredient – the heart’s own connection to the Divine.

This brings us to the question of artificial intelligence and the soul. We live in an age when AI can compose music, write poetry, perhaps even generate Rumi-like verses at the push of a button. Could an AI ever whirl like a dervish? It might mimic the motions, calculate the optimal spinning speed to avoid dizziness, and even produce words of prayer it learned from data. But the soulful love – that spark which Shams blew upon Rumi and set him aflame – is something no algorithm can ignite. The danger, however, is not that AI will literally become a whirling dervish, but that humanity might let the qualitative dimensions of spiritual life be overshadowed by the quantitative mindset of technology. Sufi teacher Kabir Helminski warns of a transhumanist future where we consider “the merging of human beings with technology, and not just at the physical level, but possibly a merging that encroaches upon the most intimate dimensions of the soul.” If we reduce consciousness to data and prayer to programming, we risk forgetting the very mystery that makes us human. Helminski calls this “the ideology of Dataism”, a belief that everything can be modeled as algorithms . In such a scenario, the subtle, inward experiences that Sufis cherish – the state of wajd (ecstasy), the presence of khushu (humble awe), the transformative power of baraka (grace) – might be dismissed as irrelevant because they are not quantifiable. But Sufism stands as a reminder that the heart holds realities that no machine can measure. As Helminski urges, our destiny is not a “bogus level of transcendence” achieved by uploading our minds to the cloud; it is rather “to align and harmonize ourselves with the cosmological order, and in the end to upload our souls into eternity.” In other words, we are meant to transcend, but not by becoming cyborgs – by becoming more deeply human, awakened to the full spectrum of our spiritual intelligence.

Indeed, the Sufi path cultivates what might be called an inner technology – the polishing of the heart’s mirror, the expansion of consciousness beyond the ego’s cage. These are precisely the qualities that will keep Sufism alive when outer technologies dominate life. Can Sufism survive? History offers hope: Sufism has always adapted. When printing presses spread books, Sufis used them to publish mystical poetry. In the age of the internet, Sufi teachings and Rumi’s verses have exploded across social media, reaching seekers who might never have found a Shaykh in person. One could say Rumi has “gone viral” in the West precisely in the digital era. His words of love and unity have found a new life online – albeit often taken out of context, they still carry a fragrance that many find alluring. This suggests that even in a world of high-tech abstraction, there remains a hunger for the depth and sweetness of spiritual meaning. Sufism’s challenge is to offer an authentic oasis in the cyber desert, to be a well of real water in a world drinking simulacra. It might mean small circles of dervishes meeting in urban apartments for zikr, their smartphones turned off, sitting on Zoom calls only when necessary but knowing that the real work happens in the quiet of dawn meditation. It might mean new metaphors – speaking of the “firewall of the ego” or the “download of grace” – whatever bridges the understanding of a new generation to the timeless truths.

However, one must also consider whether the core of Sufism – which often emphasizes sobriety in God and solitude (khalwa) – can thrive in a culture of perpetual connectivity. Sufi masters traditionally underwent long retreats, wandering in deserts or mountains to seek God in seclusion. How would that translate to today? Perhaps through intentional “digital solitude”: periodically disconnecting from all devices to reconnect with one’s spirit. Already, we see people taking meditation retreats where they hand over their phones for days. A Sufi practitioner might perform a modern khalwa by simply creating a sacred space in his apartment, free of electronics, where each night he spends an hour in candle-lit whirling or silent remembrance. The form evolves, but the intent remains: to empty oneself of distractions and be present with the Beloved. Paradoxically, as the world becomes more virtually intertwined, the value of silence and presence increases. What was once normal (a quiet evening alone) is now a luxury or a discipline. Thus the Sufi path of inwardness could become more appealing as a remedy to digital burnout – a way to detox the soul from constant noise.

Consider the image of a future seeker: She lives in a bustling megacity, AI assistants managing her schedule, VR entertainment on demand. One evening, overwhelmed by a sense of meaninglessness, she slips on a headset not for escape but to join a guided Sema. In her small living room, she begins to turn. The software surrounds her with a simulation of the celestial heavens, but something unexpected happens – as she whirls, tears come to her eyes. She feels a warmth in her chest, an inexplicable joy welling up. Removing the headset, she continues to spin in darkness, the virtual visuals now unnecessary. In that moment, she’s no longer thinking of the technology at all; she’s praying. The motion of whirling has opened her heart to an authentic experience of the Divine. This little thought experiment shows that Sufism can not only survive but may blossom in new ways: by using the tools of the time as vehicles, not idols. The danger is when the tool becomes the master. But guided by genuine spiritual intention, even advanced technology can serve as a canvas for devotion.

Ultimately, the survival of Sufism in a digital world will depend on the sincerity of its practitioners and the flexibility of its presentation, not on the preservation of outward forms. If the heart of Sema is understood, it matters little whether it’s done in a Turkish tekke or an online group. As long as there are lovers of God willing to “turn” toward their Beloved, the prayer will continue. The great Persian poet Hafiz once wrote a prayerful poem that seems fitting here: “Untangle my feet from all that ensnares. Free my soul, that we might dance – and that our dancing might be contagious.” . In these lines, Hafiz speaks across centuries to our modern condition. We are entangled by so many snares – materialism, cynicism, endless data – and we seek freedom to dance the sacred dance of life. If one soul breaks free and dances, it encourages others to join. The whirling prayer of the dervishes has always been meant to be contagious in the best way: spreading love, inspiring awe, reminding onlookers of the possibility of joy and connection. Even today, when tourists in Istanbul or Konya witness the Whirling Dervishes, many report feeling a strange peace or emotion overcome them as the white figures spin in unison. There is a transmission happening beyond words.

Sufism’s enduring power lies in such transmissions – heart to heart, presence to presence. Technology can carry words and images, but the state must be carried by living hearts. Shams Tabrizi is long gone in person, yet in Rumi’s verses his spirit still whispers. Rumi himself is not here, yet his baraka (blessing) touches people who read his poems or hear the reed flute’s song. Likewise, the Mevlevi dervishes continue to whirl, keeping the channel open. They often say that during Sema, the dervish becomes “a threshold” (after all, the Persian word darwish means threshold) – a threshold between this world and the unseen. He stands at the border of the material and spiritual, inviting others to glimpse the beyond. If our future world finds new thresholds, new interfaces between seen and unseen, Sufism will walk through those doors. It may take on strange new guises, but as long as the wine of Divine Love flows, there will be cups raised to receive it. The form of the cup can change – clay, glass, crystal, or digital – but the wine is the same.

In the end, it comes back to the human heart’s capacity to yearn and to love. Shams Tabrizi taught that the path to Truth is a matter of the heart, not of the head . That teaching is perhaps more important in the 21st century than ever. The “head” – our rational, calculating mind – has achieved wonders in creating virtual worlds and intelligent machines. But without the heart, those remain lifeless in meaning. The heart brings quality, beauty, and soul into whatever it touches. A line often attributed to Rumi says: “Dancing is not just getting up painlessly, like a leaf blown on the wind; dancing is when you tear your heart out and rise out of your body to hang suspended between the worlds.” . This visceral image of tearing your heart out suggests complete self-giving – a willingness to surrender one’s ego for the sake of love. Such totality is the mark of Sufi spirituality. It may sound intense, but it points to the ecstasy available when one lets go of the fear and plunges into the divine mystery. Whether one lives in 13th-century Konya or 22nd-century New York, that leap of love is available. It does not require high technology – in fact, it requires simplicity, a stripping away of all artifice.

So, can the whirling prayer survive? Perhaps the better question is: Can we survive without it? In a world of dizzying distractions, the intentional dizzying of Sema is a paradoxical cure – a dizziness that brings sobriety, a motion that leads to stillness. As the dervish spins, the world blurs and only God is clear. When he finally comes to a stop, dropping his arms and returning to ordinary time, he bows in gratitude. The ceremony ends, but the prayer continues in his now-silent heart. Likewise, as we navigate the accelerating turn of modern life, we may discover that Sufism offers a still center, a compass pointing to True North. We may not all whirl physically, but we can turn inward at any moment. “Turn, and the world around you turns differently,” Shams might say. The legacy of Shams Tabrizi and Rumi is not a relic of the past; it is a living invitation. It invites each of us to become, in our own way, a “whirling dervish” of the heart – to find that axis of love inside around which all things revolve in harmony.

In the poem-book that Rumi named after Shams, one of the concluding lines addresses the seeker directly: “Whoever has heard of me, let him prepare to come and see me; whoever desires me, let him search for me. He will find me – then let him choose none other than I.” . The me in these lines can be read as the Divine speaking, or Shams as the embodiment of divine love, or even Rumi himself as Love’s voice. In any case, it is a call to seek and to commit wholly. In an age where we “scroll” instead of seek, where we sample spiritual quotes but often shy away from deeper commitment, these lines dare us to truly search and truly find. The Sufi path requires that commitment – a love that makes one “choose none other.” If that fire can be kindled in even a few hearts amidst the digital storm, those hearts will be the beacons that carry Sufism forward. The form will adapt, but the flame will not go out. The future dervish might wear a VR visor or an AI-powered robe that lights up with every heartbeat; or perhaps she will simply wear jeans and turn in her bedroom unseen. What matters is that the turning is toward God.

The article you have just journeyed through is itself a kind of Sema – weaving classical Sufi wisdom with futuristic imagination, circling around the central question of maintaining spiritual depth in a technological age. If it has succeeded, you might feel a bit of that sacred motion within you now: the urge to close your eyes, spread your arms, and surrender to the music of your own soul. As Hafiz beautifully implored, may our dance be contagious, spreading from heart to heart. The world may yet be unified in an unseen circle of lovers whirling in remembrance – some in monasteries, some in cyber space, all linked by the thread of love. In the timeless words of Rumi: “Now is the time to unite the soul and the world. Now is the time to see the sunlight dancing as one with the shadows.” . The Sufi will continue to whirl, in sunlight or shadow, in clay or in silicon, as long as the prayer of love calls out from the human heart. And in that whirling, there is an unbroken connection – a form of prayer that forever says, “Here I am, O Love, turning toward You.”